Jokowi’s First Development Plan: Infrastructure

Joko Widodo, better known as Jokowi, is in his second period of the presidency in Indonesia, which had, during his first period, he concentrated policy on the development of the Indonesian economy, especially through investment in the development of the development infrastructure (Hill and Negara 2019). Jokowi knows that infrastructure has been the “Achilles Heel” for developing countries like Indonesia, yet he focused on investment, health systems, and education during his second term. The last law on labour, the Omnibus law, was confirmed by the Jokowi administration last October during the COVID-19 pandemic. The new law will administer labour, environmental and investment regulation (Arifin 2021, Mahy 2021)

Nevertheless, what will be the cost-benefit of this decision? Time will tell whether the Omnibus law will have a good effect or a dangerous effect. However, the people did not see any good in this new government choice, as evidenced by responses from the labour and student movements and academics. A strong infrastructure is essential for the effective functioning of the economy, particularly for reducing economic gaps in the region and reducing the poverty rate. (Firework World Economic Forum 2014).

Comparing the last year of the Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono presidency with the start of the Jokowi period, the stark difference in approaches to economic development is clear. The first act that Jokowi did was to end the fuel subsidy, a subsidy that cost the Government 17.8 billion $ in 2014 and 4.8 billion $ in 2015, enough to divert to a start in promoting the infrastructure, improving the health system, and education ( Negara 2016). Indeed it was already clear that Jokowi planned to dedicate priority to infrastructure investment in the draft of the Medium Term National Development Plan or in Indonesian language RPJMN 2014-2019, where the Government hoped to increase 7 % GPD starting in 2016 (RPJMN report 2014). However, the anticipated GDP target was not reached. Instead, the GDP of Indonesia has grown just 4 /5 % YoY during the slowdown of the global economy created by the COVID-19 pandemic.

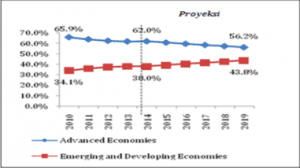

Nonetheless, Jokowi wanted Indonesia to be more economically independent, also not wanting Indonesia to fall behind other countries in Asia like India, China, and Vietnam where infrastructure was developing apace. During his first semester, according to BAPESSAN analysis, no longer Europe and America, but Asia and the Pacific would be the centre of the world economy (Graphic 1).

Graphic 1 demonstrated the prediction made by BAPESSAN.

Source : Bappenas, Oxford Economic Model

Furthermore, Jokowi had understood that the national balance was insufficient without investment from foreign sources, based on investment in infrastructure. Jokowu also knew that, compared with other developing countries like Vietnam or China, Indonesia has a slow and complex bureaucratic system, especially for the legacy of foreign investment. These factors have combined to push the Government to create the controversial new Omnibus Law, cutting many bureaucratic knots in investment to the environment and labour laws.

In this scenario, Jokowi has understood that without foreign Investment, Indonesia cannot develop faster. After the end of Yudhoyono’s period and the start of Jokowi’s period, the budget that Indonesia needed for investment in infrastructure was 300 billion US$, yet the national public finance of Indonesia afforded just 20% of that amount (Deny Sidharta and Jared Heath 2014). According to Hall Hill and Negara (2019), one of the challenges in meeting Indonesia’s massive investment in infrastructure ambition is the weak tax system causing the government shortfalls in the public reserve. Therefore there were a few associated challenges that the Jokowi administration needed to resolve. The first was financing, and the others were land clarity, planning and projecting (Utomo 2017). In addition, Jokowi also faced another huge problem from entrenched local corruption festering through years of power decentralism after the end of the Suharto regime ( Nugroho 2020). In combination, tax inflation, excessive bureaucracy, and massive corruption have pressured Jokowi to accelerate the Omnibus Law to fix his plan to develop the nation’s economy.

The Omnibus Law: Worker, Gender, Environment Rights

During the emergence of COVID-19 in Indonesia, the Jokowi Government and The House of Representatives accelerated the procedure for acceptance of the new Omnibus Law on labour in Indonesia to repair the bureaucracy that has, according to the President of Indonesia Joko Widodo (2020), slowed down investment in the country. The problems that made Jokowi create the Omnibus Law were hyper-regulation and bureaucratic knots (Anggraeni, Rachman 2020). According to the Regulatory Quality Index ranking, Indonesia is on the lowest level. Another problem is the decentralisation of power that has increased corruption at the local level (Johannes Nugroho 2020) and slowed down investment procedures. However, the effects on workers, gender, indigenous affairs and the environment are worrying.

Many scholars and NGOs have demonstrated their disappointment to the Government. The Omnibus Law is associated with profound adjustment to legislation that otherwise presents obstacles to investment, including the revision of 79 laws, reorganisation of legislation into 11 clusters and adjustments to more than 1000 articles, including those impacting labour law, social law, and national social security agency law (Amnesty International 2020). Many protections from the 2003 labour legislation have been deleted or modified. A new law on wages and job security is considered a threat, specifically because it does not consider inflation rates for the minimum wage. Therefore is revokes the set city district minimum wage. In practice, without inflation and cost living criteria for determining the minimum wage, poor areas like Papua are further weakened with not enough income to cover the daily cost of living (Usman Hamid 2020).

Another issue of concern is the relative security of the worker when signing a job contract. Under the Omnibus Law, employers cannot offer a permanent job contract but can provide a temporary contract for an indefinite period, meaning that the worker can more easily lose their job. The review of Labour Law presents a new threat with the possibility of performing “work for free”, meaning extra work that does not produce income for the worker. Moreover, article 93 (2) of the Labour Law does not allow for paid time off during menstruation, which is a significant violation of women’s rights.

Additionally, there is concern from environmental NGOs that the new law will increase deforestation in Indonesia (Madani 2020). There is a possibility that by 2056, 5 areas of Indonesia, Riau, Jambi, Sumatra, Bangka Belitung and Center Jawa, will lose their natural forest. Article 29,30,31 of the new law retains the AMDAL (environmental impact assessment requirements) but deletes the function of an independent committee composed of NGOs and activists for the environment. The new law further supports deforestation to increase the palm oil plantation, a dangerous threat that the Government has endorsed with the amplification of the work. It will probably negatively affect the local people who live in the areas that will be deforested, particularly art. 50 (2) sentences 12A and 17B prohibit farming in forestry areas and commercial activities in unregistered forests (Hamid and Hermawan 2020). How to report the NGO Human Rights Wacht (HRW), this is a violation of international norms, such as those expressed in the ICESCR and the UN declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples (HRW 2020 )

On the one hand, the Omnibus Law was created by the Jokowi administration to push ahead with infrastructure and economic development through investment. The new Labour Law attempts to remove excessive bureaucratic administration and red tape relating to foreign investment regulation, liberalizing all foreign investor businesses in any sector, except for currently heavily regulated, banned or illegal industries such as weapons or illicit drugs (Shen and Siagian 2020). The Labour Law also brings tax reforms, an extremely complex issue because tax evasion is one of the highest in the region. The Omnibus Law aims to reduce the tax to 20% for private companies and 17% for Indonesia-listed companies, while foreign workers will be exempt from paying personal income tax on income derived outside Indonesia (Shen and Siagian 2020). On the other hand, the Omnibus Law potentially damages workers’ rights, especially women and indigenous workers, so while investment may grow, the price will be paid by erosion in democracy and civil rights.

References:

Anggraeni,R, Rachman, C.I . (2020). Omnibus Law in Indonesia: Is That the Right Strategy?, Atlantis Press, Advances In Economic, Business and Management Research, volume 140 https://doi.org/10.2991/aebmr.k.200513.038

Amnesty International. (2020) Commentary on the labor cluster of the Omnibus Bill on Job Creation ( RUU CIPTA KERJA) Jakarta, Index: ASA 21/2879/2020

Amnesty International. (2020) Omnibus Bill on Job Creation Poses “Serious Threat” to Human Rights,

Amnesty International. (2020) Submission to United Nations committee on the elimination of discrimination against woman

Arafin, S. (2021), Illiberal Tencencies in Indonesia Legislation:te case of the omnibus law on job creation. The Theory and Practive of legaslation Juornal, Vol 9 N.o 2 https://doi.org/10.1080/20508840.2021.1942374

Bland B. (2020), Man of Contradictions, Joko Widodo and the struggle to remake Indonesia, Lowy Institute, Penguin Random House Australia

BAPPENAS, Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah 2014-2019

Breuer L.E, Guajardo J, Kinda T. (2018) Realizing Indonesia’s Economic Potential, International Monetary Fund (IMF)

Emont J. (2016) Visionary or Cautious Reformer? Indonesia President Joko Widodo’s Two Years in Office https://time.com/4416354/indonesia-joko-jokowi-widodo-terrorism-lgbt-economy/

Firduas F. (2020) Indonesia Fear Democracy is the Next Pandemic Victim, Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/04/indonesia-coronavirus-pandemic-democracy-omnibus-law/

Hamid. U., Ary (2020). Hermawan, Indonesia’s Omnibus Law is a bust for human rights, New Mandala. https://www.newmandala.org/indonesias-omnibus-law-is-a-bust-for-human-rights/

Hill H, Negara S.D. (2019) ; The Indonesia Economy in Transition, Policy challenge is Jokowi era and beyond, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute

Human Rights Watch. (2020) Indonesia; New Law Hurts Workers, Indigenous Groups, Massive Omnibus Bill Passed Little Public Consultation. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/15/indonesia-new-law-hurts-workers-indigenous-groups

HRW Ihanuddin, Krisiandi. (2020) Jokowi Ungkap Alasan RUU Cipta Kerja Dikebut di Tengah Pandemi, Kompas.com

Negara D. (2016 ) Indonesia’s Infrastructure Development Under The Jokowi Administration, Southeast Asian Affairs, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute

Nugroho J. (2020) Indonesia’s Omnibus Law won’t kill corruption , The Lowy Institute. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/indonesia-s-omnibus-law-won-t-kill-corruption

Madani (2020) . Tinjuan Risiko RUU CIPTA kerja terhadap hutan alam dan pencepain komitmen iklim Indonesia. https://madaniberkelanjutan.id/2020/05/06/tinjauan-risiko-ruu-cipta-kerja-terhadap-hutan-alam-dan-pencapaian-komitmen-iklim-indonesia

Mahy,P. (2021) Indonesia ‘s Omnibs Law on Job Creation: Reducing labour Protections in a Time of Covid-19, Monash Business School, Monash University, Labour, Equality and Human Rights Research Gruop Working Paper N.o 23

Mighty Earth. (2020) Indonesia’s Omnibus Bill Approval Poses Dire Threat to Anti-Deforestation Efforts. https://www.mightyearth.org/2020/10/05/indonesias-omnibus-bill-approval-poses-dire-threat-to-anti-deforestation-efforts/

Shen,J.,Siagian,C. (2020). Indonesia‘s Omnibus Law: A magic wand amidst a global pandemic? https://singaporeglobalnetwork.gov.sg/stories/business/indonesias-omnibus-law-a-magic-wand-amidst-a-global-pandemic/

Sidharta D, Jared Heath. (2014) Building Effective Partnerships, Jakarta Post

World Economy Forum (2014) The Global Competence Index 2014-2015 www.weforum.org/gcr.

Utomo, Wahyu. (2017). Tentang Pembangunan Infrastruktur di Indonesia. kppip.go.id.

About the Author:

Aniello Iannone is a candidate for Master of Political Science, Diponegoro University, and a junior analyst at the Institute of Analysis and International Relations (IARI).