Introduction

With a population of 260 million people, Indonesia is the fourth largest country globally and one of the most dynamic economies in the global market. According to the World Bank, Indonesia is now included in the status of a middle-income country. The economy in the country is running smoothly, especially during the last decade following the economic contraction caused by the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998. Due to its fairly rapid economic development, Indonesia has become a developing country and the first economic power in Southeast Asia. Its role in ASEAN continues to be important. Indonesia’s political and economic structure has changed over the years since its independence. In 1950, after the end of Dutch colonialism, economic and political development focused on the agricultural sector to realize a self-sufficient agricultural system by 1960. In the middle of 1970-1980, after the crude oil price fell, the Indonesian economy rapidly developed with urbanization and industrialization programs, for This Indonesia occurred as a consequence of the political change from crude oil exports to manufactured exports.

After the Soeharto regime and the financial crisis in 1998-1999, Indonesia’s economy and politics progressed rapidly, and by 2004-2008 the GDP increased by 5%. During 2008-2009, the slowing down of the global economy did not have a high impact on the Indonesian economy, but GDP increased by 4% until the end of 2019. However, when the SARS-CoV-19 pandemic began to emerge, the Indonesian economy was negatively impacted. Indonesia is at significant risk of falling into the Middle Income Trap (MIT), and once in, it will not be easy to get out. According to the Coordinating Minister for the Economic, Airlangga Hartono, the Omnibus Law or the Job Creation Bill that the Joko Widodo 0.2 government recently passed could be a good weapon against MIT. This law is highly controversial; the effects of this reform will have a profound and lasting impact on the Indonesian economy that will last for decades. However, the Omnibus Law has been criticized. Public opinion and students for its negative impact on the rights of the environment, workers, and society.

The Middle Income Trap

The definition of Middle Income Trap or MIT is not universal; so far, no single general definition can explain its meaning. However, five main definitions can be used to understand the status of the included countries in MIT. The first is a non-empirical interpretation, based on the opinion of Gill and Kharas (2007), with MIT as a status where an economy has experienced a sharp decline in economic dynamism after successfully transitioning from low to middle-income status, presenting as stop-and-go growth, not steady long-term growth in productivity and income. Thus, it is intended to prevent the economy from moving to high levels of income.

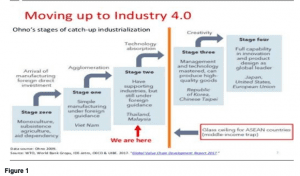

Kenichi Ohno (2009) also expressed the same opinion that a developing country must follow several phases that assimilate. This method is known as “catch-up Industrialization” or “Breaking the Glass Ceiling” (Figure 1). The approach rests on structural and economic development in which the nature of the production structure and its context is on learning and international competitiveness issues. Furthermore, according to Ohno (2009), middle-income countries face slow growth, but the analytical framework for understanding slowing growth is different and the policy prescription.

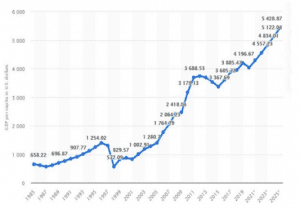

Based on Ohno’s theory, Indonesia is now in stage 2. This stage is accompanied by increased accumulation and production so that the supply of domestic spare parts and components also begins to increase (Ohno 2009: 64). It must enter from FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) and local supplies, which makes industry grow with a moderate increase in internal value, but production remains under foreign management. Another MIT interpretation is passing the income threshold, and this interpretation is the empirical interpretation of the income level as the threshold for MIT. Spence (2011) suggests that a threshold should be established through a rate of between USD 5,000 and USD 10,000 per capita income (KKB). He said this was because he saw that countries willing to transition to the level of developed countries were facing difficulties. According to the World Bank, Indonesia has entered into the middle to upper income (Table 1). This status was established following Joko Widodo’s political-economic plans during his first term. Jokowi plans to focus on infrastructure, especially bridges, highways, airports as set out in the ‘nawacita’ plan.

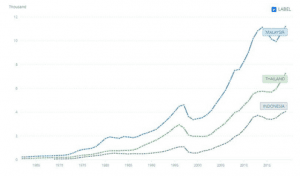

Tabel 1 : GNI rates for Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia until 2020

Source : World Bank Data

Indonesia’s status is classified as middle income because the country’s GNP has increased to $4,050 per capita. According to the World Bank, when the country’s gross national income or GNI per capita is $4,046 -$12,535, the country can enter middle to upper-income status. It can also be seen in table 1 by the World Bank. However, the path to becoming a developed country is still long and complicated, and there is a very high chance that Indonesia will be trapped in MIT. Based on the MIT theory through income threshold, middle-income countries find two threats; the first is a trap for capital income between $10,000 and $11,000, and the second the per-capita income between $15,000 and $ 16,000 trap (Eichengreen, Barry, Donghyng, Pak and Kwanho Shin, 2013).

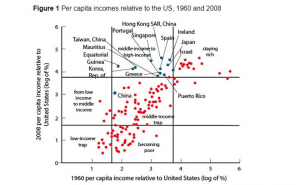

Agen and Canuto (2012) suggest that the MIT analysis must pass the catch-up benchmark, which, in MIT analysis, takes data from the relative income threshold (Figure 1)

Graph 1

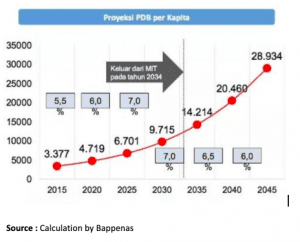

The threshold used to determine whether a country is stuck at MIT is between 5% and 45% of US GDP per capita. A study was conducted in 2012 to see how many countries have entered MIT and how many countries are high-income countries. However, this could become an example for Indonesia at present. According to Minister Bambang Brodjonegoro (2020), Indonesia will transition and enter the status of a high-income country by 2025 at the latest (Graphs 2 and 3).

Graph 2

Graph 3

Felipe, Abdon and Kumar (2012) said that countries trapped as MIT could be seen from the time threshold of 28 years for low, middle-income countries (KKB increases by 4.8% per year), and 14 years for high middle-income countries (KKB increase per year 3.5%). If these countries exceed the threshold number of years, they will be classified as trapped in MIT. However, Woo (2012) and Hawksworth (2014) conducted MIT analysis from another perspective. They analysed data from the Catch-Up Index (CUI). According to them, these countries could get stuck as MIT if they showed no inclination to meet global economic leaders from, for example, the US or China. CUI revealed that these countries enter into MIT as a result of dividing their income level: for example, based on the US income level, if Indonesias result is more than 55%, the country is classified as a high-income country, but if the result is 20% it will be called low income and or middle-income country. However, Hawksworth (2014) states that countries that want to leave MIT must follow several factors: economic stability, progress and social cohesion, technological advances, legal policies, institutional regulations, and sustainable development.

Based on this theory, it can be said that the countries included or trapped in MIT are developing countries (Pruchnik and Zowczak 2017: 18). The demographics are not favourable, especially considering the ages of the working class; if the workers are older, the saving rate will decrease compared to countries that have a younger working-class (Canning 2004, Ayiar 2013). Then, when the level of economic diversification is low, the country’s economic structure is important to continue the level towards high income. Middle-income economies must move up the value chain to maintain their high growth rates. Another consideration is inefficient financial markets, according to the World Economic Forum 2014, as they are negatively associated with a possible slowdown consisting of indicators such as availability of financial services, availability of venture capital and ease of access to loans. It also relates to inefficient raw infrastructure because the infrastructure with great quality is important in leaving MIT status (Agenor and Canuto 2012), especially based on the 2014 WEF (World Economic Forum), electricity, transportation, and communication infrastructure.

One factor that can assist a country leave MIT status is innovation. Low levels of innovation can cement a trapped state in MIT. Weak institutions can also be a problem for becoming a high-income country, especially if impacting the efficiency of the legal framework, protection of property rights, and the quality of government regulations which are important to encourage innovation and design activities.

Last but not least is an inefficient labour market and human capital. The country should make efficient use of the talents of workers, with flexibility in setting wages and hiring and firing practices.

How can Indonesia avoid being caught up in MIT? Can the Job Creation Law be a solution?

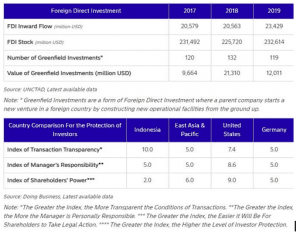

As explained above, Indonesia has become a high middle-income country. Based on the World Investment report 2020, FDI in Indonesia increased by 14% between 2018 and 2019 (figure 2).

Figure 2

Even though the Indonesian economy is developing and its status is rising, several factors can trap Indonesia in MIT status, such as high costs that can reach 60% for illegal transfers. WB has proven that the legal, economic framework is less effective than other Asian countries.

In addition, the business community generally considers the administration of justice and taxation and customs to be corrupt and arbitrary. Another factor is limited infrastructure, particularly the gap between Java and the outer or isolated islands, the unemployment rate, poverty and China’s high dependence on export commodities, thereby increasing the risk of Indonesia’s economic slowdown. Human capital in Indonesia is also one of the issues that can trap Indonesia in MIT status. Based on the latest data from the World Bank, the 2018 Human Capital Index in Indonesia is 0.53, meaning the average capacity of worker productivity is 53% of its full potential with access to education and the health system.

One of the “weapons” of the Indonesian government and Jokowi is 0.2 government is the approval of the Job Creation Law or the Omnibus Law. The Minister of Finance (Menkeu) said that she strongly agreed with the Law because, according to her, the Law will help State innovation, public creativity and various incentives to facilitate entrepreneurship in increasing income. Teten Masduki, The Minister of Cooperatives and SMEs, said that this regulation would make it easier for business actors to benefit, especially those from Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises. The Omnibus Law attempts to shorten the hyper and heavy regulatory structure in Indonesia, which, until now, has been an overlapping legal issue which is a major problem economically as it slows down competitiveness nationally. For a country like Indonesia that wants to become a country with a high income by 2035, competitiveness is important because, with fast and uncomplicated competitiveness, the investment will be more attractive to Indonesia.

The World Bank (2018) says that because Indonesia has a multi-layered structure, Indonesia is 73rd out of 190 countries and ranked 50th for competitiveness. It means that the bureaucracy in Indonesia has too many regulations, which slow down investment. Because of this problem, low human capital is increasing and also the infrastructure needs to be improved throughout Indonesia. The government has accepted the Omnibus Law because it aims to deal with vertical and horizontal public policy conflicts effectively and efficiently, harmonizing government policies at the central and regional levels, and simplifying a more integrated and effective licensing process. It is regulated into an integrated policy to break the convoluted bureaucratic chain and improve coordination between related agencies. In addition, the Omnibus Law can provide legal certainty and legal protection for policymakers.

Conclusion

The government must invest in Human Capital through education and the health and welfare system. Education is important to enable the level of knowledge and quality of society to be productive. Further, investment policies are less complicated so that foreign investors do not encounter bureaucratic difficulties. Indonesia is one of the countries with a very strong economy in Asia and the world, so the government should focus on following investment trends or trends followed by other countries, such as those focused on the green economy, infrastructure and technology. It is also important to focus on infrastructure for underdeveloped islands like North Sulawesi, Kalimantan and several areas in Sumatera. Anti-political corruption is a critical factor, as is political status in the country, which can also alter economic performance.

Indonesia has all the ingredients to become a high-income country in 2035-2040 but needs vigilance. Although the Omnibus Law is heavily criticized, it could be the last stage to move out of middle-income status, but only time will tell whether this will fail or succeed. It is necessary to focus on human capital and education, especially among the younger generation, while poverty levels must be reduced and infrastructure must be innovated, including in areas outside Java island. The bureaucracy must be facilitated, which may be facilitated by the Job Creation Law. This period is very important, as after Indonesia overcomes the COVID-19 outbreak and its economy recovers, the government needs to focus on improving domestic policies and infrastructure in under-developed areas and improve infrastructure in more developed areas such as Java.

Refrences

Agenor P., Catuno O. (2012) Middle-Income Growth Traps. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6210, The World Bank

Asia Development Bank -BAPPENAS Report (2019), Policies To support the development of Indonesia’s manufacturing sector during 2020-2024

Ayiar S, Duval R. Puy D., Wu Y., Zhang L ( 2013) Growth Slowdowns and the Middle-Income Trap IMF Working Paper WP/13/71, International Monetary Fund

Breuer, Luis E., Guajardo J., Kinda T. ( 2018), Realizing Indonesia Economic Potential, International Monetary Fund

Bukowski M., Helesiak A., Petru R., (2013) Konkurencyjna Polska 2020: Deregulacja i Innowacyjnosc. Warszawski Instytut Studiów Ekonomicznych ( WISE)

Camilla Homemo, (2019) Pengembangan modal manusia adalah kunci masa depan Indonesia, World Bank

Diemer A., Iammarino S. Rodriguez-Pose A., Storper M.; European Commission (2020), Falling Into the Middle-Income Trap? A study on the Risks for EU Regions to be Caught in a Middle-Income Trap, Final Report, LSE Consulting June 2020

Eichengreen, Barry, Donghyung, Pak and Shin Kwanho, (2013), Growth Slowdowns Redux: New Evidence on the Middle-Income Trap, NBER Working Paper, 18673, January

Faisal Basri, Gatot Arya Putra, (2016) Escaping the Middle Income Trap in Indonesia; An analysis of risks, remedies and national characteristics, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung,Jakarat, ISBN No: 978 602 8866 170

Filipe J., Kumar U., Galope R., (2014) Middle-income Transitions: Trap or Myth? Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series (421)

Gill I. Kharas H. (2007) An East Asain Renaissance, Ideas For Economic Growth, The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank

Huang B., Morgan Peter J., Yoshino N. Avoiding the middle-income trap in Asia; The role of Trade, Manufacturing, and Finance (2018), Asian Development Bank Institute

Ricca A., Rachman Lestari I. C., (2020) Omnibus Law in Indonesia: Is That the Right Strategy? Pancasila University, Jakarta -Republic of Indonesia, Advances In Economics, Business and Management Research, Volume 140, International Conference on Law, Economics and Health (2020), Atlantis Press

NN., Omnibus Law : Solusi dan Terobosan Hukum, 2019, Indonesia.go

NN “RUU Omnibus Law : Omnibus Law; Solusi dan Terobosan Hukum, diakses melalui indonesia.go

Ohno. K. (2009) The middle Income Trap, Implications for Industrialization Strategies in East Asia and Africa

Pruchnik K., Zowczak J. (2017), Middle-Income Trap: Review of the Conceptual Framework, Asia Development Bank (ABD) Institute, N 760 July 2017

Jawapos, 12/10/2020 Sri Mulyani: Omnibus Law Entaskan Indonesia dari Middle Income Trap

Woo W., Lu M., Sachs J., Chen Z., (2012) A New Economic Growth Engine for China Escaping the Middle Income Trap by Not Doing More of the Same, Imperial College Press.

World Investment report 2020; International Production Beyond the Pandemic, United Nations, New York

About the author:

Aniello Iannone is a candidate for Master of Political Science, Diponegoro University, and Junior analyst at the Institute of Analysis and International Relations (IARI).