What the Mekong mean for Security in Southeast Asia: Hydro-Hegemony and Food Insecurity, or Cooperation by Thomas Robert Bartley

Southeast Asia is a region developing and expanding fast in terms of population, importance, and interconnectedness. While the future beckons promisingly for the continued success of the region, potential backsliding into instability threatens to change this trajectory. Non-traditional aspects of security now take the forefront of issues threatening this backsliding. While changes in the balance of power between Southeast Asian nations or the efficacy of institutions remain integral to the region’s future, threats like a warming and unpredictable climate or breaches in cyber-security now have the potential to drastically change the state of security in the region.

The issue with perhaps the most disruptive potential is that of food security. While this largely has been considered an issue or goal of development studies, its impact on the security of nations is now being recognised as significant. Studies conducted for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) show striking patterns of correlation between rising food prices and the emergence of disruption and conflict. This can range from spikes in anti-government sentiment and irregular migration, to the outbreak of civil conflict and upticks in participation in rebel movements and organised crime., Disruptions to the affordable and ready access to food will inevitably have severe impacts on the stability of any country. Reporting from Foreign Policy summates this idea in stating that lack of food security will have ‘serious implications for global political stability’, and that it could lead to ‘mass displacement as people migrate to more arable [regions] in search of stable food supplies’.

The ability of food insecurity to destabilise at the individual level as well as the national and international levels is what makes this threat particularly dramatic. Within the Southeast Asian region, food security is increasingly being cited as a cause for concern. According to recent indexing produced by The Economist, the region, not including Singapore, ranks 1.3 points below the global average., This ranking has the potential to deteriorate significantly given concerns for the long-term agricultural productivity in the region. Aside from sheerly security concerns, the risk also is also compounded by economic dimensions as import-export balances and national income are affected by reductions in agricultural production, requiring a higher reliance on foreign markets.

The area of most concern within Southeast Asia is the potentially exponential deterioration of production depending on the Mekong River System. As the river flows through Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Myanmar, deterioration in the system would represent a significant issue afflicting Southeast Asia as a whole. The river currently discharges an estimated 475 cubic kilometres of fresh water annually, feeding a delta of 795,000 km2 in size. The benefits of this flow are felt to such an extent that the river is sometimes referred to as the ‘mother of waters’, reflecting its importance to the lives of tens of millions of people.

Deteriorations in the river system are a particular concern for the Mekong Delta region of Vietnam and the Tonle Sap region of Cambodia. The former of these regions is responsible for 90% of the rice exports of Vietnam and the livelihoods of 17 million people, whilst the collapse of the later would define Cambodia as a failed state., On current trajectory, Laos and Cambodia are predicted to be unable to match domestic production with domestic demand by 2030. While these events would cause significant harm and displacement for the people of these countries, the effects of this contingency would inevitably spill across borders, potentially causing sharp increases in food prices and reductions in food availability throughout Southeast Asia. This undoubtedly would be felt in conjunction with other economical or security concerns that go along with having increasingly insecure neighbours.

This issue takes particular relevance given current developments afflicting the Mekong. As the river crosses through multiple nations, many issues persist around shared management of the system. Here, unilateral decisions, especially those like the damming of the river, are a particular cause for concern. These developments can have drastic impacts for downstream productivity. In particular, projects such as damming are seen to have a substantial impact on sediment deposits and water availability for downstream populations. This makes agricultural yields in any given area harder to predict, hurting the ability of small-scale farmers to plan for the future, and making agricultural investments seem riskier. Additionally, increasing rates of glacial melt at the sources of the river in the Tibetan Plateau further complicate the issue by causing seasonal flows to become increasingly erratic. While these developments may be approached and mitigated through the use of effective multilateral action, there are strong incentives for some states to resist concerted action, or to otherwise seek benefit from their geographic positioning at the detriment of other regional players.

In explaining why this may be the case, considering how cooperation on this issue is incentivised or disincentivised provides a road map for current patterns of behaviour. When it comes to the issue of increasing rates of glacial melt, the reasoning behind lack of effective action is similar to lethargies affecting other environmental issues. That is, as the phenomenon is caused by increasing carbon emissions globally, the attribution of blame or responsibility becomes difficult, hindering effective approaches to the issue. The cost of action would also be high, likely requiring significant systemic change with no promise of reciprocation from other stake holders. However, costs of inaction could verge on being catastrophic. A UNESCO report states that the glaciated regions of Asia are the fastest receding in the world. The report estimated that the water requirements of over a billion people are met by these glaciers. In South Asia alone, increased rates of melt are expected to affect well over 177 million people in terms of income and livelihood.

As most Southeast Asian nations are positioned geographically far from the glaciated areas feeding the Mekong, it will however remain difficult to direct regional attention to the issue. East and South Asian countries positioned relatively closer to the sources of the river may have a greater role to play in initiating dialogue and coordinated responses. Considering that the health of the Mekong is integral to the futures of some Southeast Asian nations, such actions would signify a great deal of regional responsibility and forward thinking on the part of instigating nations. This may entail the creation of water sharing agreements, information sharing initiatives, and memorandums of understanding regarding norms and expectations of behaviour which affects the river. An appreciation of the spill-over effects of food insecurity and broader regional malaise is required in order to make such decisions. This would come as an alternative to potential zero-sum thinking pursued through conventional geopolitics. While there are areas of concern that South-Eastern Mekong states should act upon (like unsustainable activities or overuse of the Delta), responsibility for a large amount of the river’s health lies with upstream states.

The greatest present risk to the future productivity of the region is the feared ‘sinking of the Mekong’. The Delta’s land mass (primarily located in Vietnam) is sustained through constant flow of sediment from upstream, mentioned earlier. Because of this, any alterations to these flows will impact the total land mass available for productive activities. While decreasing flows from glaciers may impact this in the future, more immediately impactful is the development of damming projects in upstream states. At the date of writing, these dams are primarily located in China with some beginning to appear in Laos. The eight currently finished damming projects have already affected around 50% of the usual sediment flows. If additional damming projects are completed as planned, sediment deposits will be restricted by more than 96% of their current levels. Such development of the river also has the potential to restrict migratory fish and their breeding patterns, further harming productivity of downstream fisheries. Fishermen in the region already express worries about the future of their wellbeing, lamenting the change in their catch from only a decade earlier.

The substantial impacts of this damming can point to potentially callous disregard for water and food security on the part of upstream states. The impacts on Vietnamese and Cambodian productive regions in particular point to large absences in regional responsibility especially as it regards policy actions from Beijing. Current publications note the effect of the Mekong’s damming to be excessive, potentially leading to complete inundation of the Mekong Delta by the turn of the century. This phenomenon will occur as the rate of sediment deposit is eventually exceeded by rates of sea-level rise; it is likely this will be accompanied by a salination of the delta, limiting agricultural and fishery productivity to a fraction of current levels. This could become a direct cause of failure for food security in two Southeast Asian nations, with certain ramifications for surrounding countries. The pursuit of energy security on the part of the Chinese state is noted, however, the benefits of these projects may quickly lead to the emergence of a flashpoint in the region. Calls from lower Mekong states to cease the damming have become louder in recent years, especially from the sub-state level. Hearing and responding to these calls is likely to bring higher levels of sustained benefit for Beijing.

The falsification of Chinese led narratives, however, prompts speculation that the behaviour is likely to be unyielding. With regards to Mekong damming, one article published by China’s Global Times is titled: ‘from being responsible neighbour to biodiversity protection vanguard’. The article criticises the prevalence of ‘Western media outlets … bashing Chinese hydropower stations, claiming that the Chinese stations at upstream of Mekong River are responsible for aggravating droughts in downstream countries’. In response to this criticism, the outlet instead claims Chinese hydropower projects have a positive role to play in flood mitigation and biodiversity promotion. This is in stark contrast with facts on the ground, where substantial flooding in Cambodia is directly attributable to the dams.

In South Asia, this pattern of behaviour is mirrored. A recent ‘super hydropower’ damming project proposed by Beijing on the Brahmaputra River also points to an apparent disregard for consequence. The project has stoked fears in India regarding declines in the availability of water in the productive regions of the river basin. The seeming disregard for these concerns has led commentators to point to the potential goal of ‘hydro-hegemony’ being pursued by the Chinese state. In commenting on the prospects of damming Asian rivers, The Diplomat notes the potential for the management of transboundary river systems to be influenced by ‘the greater socio-political context’ existing between nations. By this it is meant that there are potentially strong incentives for transboundary systems to be wielded as a tool of geopolitical leverage.

However, while the presence of transboundary rivers may exacerbate tensions, they may also be used to facilitate cooperation on a greater level. The common good of the river systems and associated environmental goods can provide a tangible source of shared responsibility. Philip Hirsch, a commentator on the region, points to this dichotomy of potential outcomes in stating that ‘perhaps in no other arena is the conflation of geopolitics with the environmental agenda as significant as in the case of transboundary river basins.’ Given the potentially disastrous effects on non-cooperation, particularly as caused through the use of damming for hydroelectric purposes, the Mekong may provide a decisive focal point for shared dialogue and future relations. Whether or not these relations provide positive dividends depends on the self-awareness of nations, and the impacts they desire to have on the region in which they reside.

Regional cooperation based around the environments of South and Southeast Asia have the potential to create a road map to future cooperation. The development of the Hindu-Kush Himalayas is overseen by a group of South and Central Asian nations (HKH countries), and the lower Mekong is, to an extent, regulated by the Mekong River Commission. The variable in this situation is whether Beijing will engage effectively in regional dialogues or exclude itself so that it may continue to act with impunity. At this current point in time, it appears as though China’s long standing ‘non-participation, non-discussion, non-recognition’ attitude is taking the lead. This strong-arming approach to regional issues misses the point of cooperation in this instance; the outcome of participation is not compromising the nation’s power, but rather seeking assurance of stability in its neighbourhood. Leveraging natural resources may reap dividends in the medium-term but it is inevitable that this will create a messy operating environment in the future. The Mekong can provide a gathering point by which nations can initiate dialogue and work towards mutually beneficial outcomes. That being said, if Beijing insists on asserting a ‘rights to territorial sovereignty’ mentality it may achieve hydro-hegemony at the cost of food security, human security, and a rapidly deteriorating regional security environment.

Bibliography

Articles:

- Biemans, C. Siderius, A.F. Lutz, S. Nepal, B. Ahmad, T. Hassan, W. von Bloh, R.R. Wijngaard, P. Wester, A.B. Shrestha & W.W. Immerzeel 2019. ‘Importance of Snow and Glacier Meltwater for Agriculture on the Indo-Gangetic Plain’. Nature Sustainability. Vol. 2. pp.594-601

- M. Kondolf, R. J. P. Schmitt, P. A. Carling, M. Goichot, M. Keskinen, M. E. Arias, S. Bizzi, A. Castelletti, T. A. Cochrane, S. E. Darby, M. Kummu, P. S. J. Minderhoud, D. Nguyen, H. T. Nguyen, N. T. Nguyen, C. Oeurng, J. Opperman, Z. Rubin, D. C. San, S. Schmeier & T. Wild 2022. ‘Save the Mekong From Drowning’. Science. vol. 376. pp.583-585

- Brochmann, N. P. Gleditsch 2012. ‘Shared Rivers and Conflict – A Reconsideration’. Political geography. vol. 31. pp.519-527

- Hirsch 2016. ‘The Shifting regional Geopolitics of Mekong Dams’. Political Geography. vol. 51. pp.63-74

Phan, L 2016, ‘The Sambor Dam: How China’s Breach of International Law Will Affect the Future of the Mekong River Basin’, The Georgetown Environmental Law Review, vol.32, no. 105, p.107

Reports:

The Economist Group, Corteva Agriscience 2022. ‘Global Food Security Index 2022’. p.3-7 The Economist Group. London.

UNESCO, IUCN 2022. ‘World Heritage Glaciers: Sentinels of Climate Change’. p.18 UNESCO, Paris. IUCN, Gland.

Journalistic Sources:

Foreign Policy. ‘The Global Food Crisis is Here’, Jason Hickel, viewed 1st December. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/08/21/the-global-food-crisis-is-here/

Radio Free Asia. ‘Despite Seasonal Floods Now, Experts See Risk of Mekong Drying Up’, Dan Southerland, viewed 5th December. https://www.rfa.org/english/commentaries/mekong-threats-09132019155403.html

The Diplomat. ‘The Precarious State of the Mekong’, Nicholas Muller, viewed 5th December. https://thediplomat.com/2022/11/the-precarious-state-of-the-mekong/

NBC News. ‘Chinese Dams on Mekong River Endanger Fish Stocks, Livelihoods, Activists Say’, Keir Simmons, Rhoda Kwan, Nat Sumon & Jennifer Jett, viewed 5th December. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/chinese-dams-mekong-river-endanger-fish-stocks-livelihoods-activists-say-n1288720

Global Times. ‘A Glimpse of China’s largest Hydroelectric Project Along Lancang River: from being Responsible Neigbor ro Biodiversity Protection Vanguard’, Zhao Yusha & Cao Siqi in Pu’er, viewed 7th December. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202209/1276056.shtml

The Diplomat. ‘China’s Super Hydropower Dam and fears of Sino-Indian Water Wars’, Genevieve Donnellon-May, viewed 12th December https://thediplomat.com/2022/12/chinas-super-hydropower-dam-and-fears-of-sino-indian-water-wars/

Author: Thomas Robert Bartley (Intern at CESASS UGM)

Can Indonesia Get Out of The Middle-income Trap: Policy Analysis

Introduction

With a population of 260 million people, Indonesia is the fourth largest country globally and one of the most dynamic economies in the global market. According to the World Bank, Indonesia is now included in the status of a middle-income country. The economy in the country is running smoothly, especially during the last decade following the economic contraction caused by the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998. Due to its fairly rapid economic development, Indonesia has become a developing country and the first economic power in Southeast Asia. Its role in ASEAN continues to be important. Indonesia’s political and economic structure has changed over the years since its independence. In 1950, after the end of Dutch colonialism, economic and political development focused on the agricultural sector to realize a self-sufficient agricultural system by 1960. In the middle of 1970-1980, after the crude oil price fell, the Indonesian economy rapidly developed with urbanization and industrialization programs, for This Indonesia occurred as a consequence of the political change from crude oil exports to manufactured exports.

After the Soeharto regime and the financial crisis in 1998-1999, Indonesia’s economy and politics progressed rapidly, and by 2004-2008 the GDP increased by 5%. During 2008-2009, the slowing down of the global economy did not have a high impact on the Indonesian economy, but GDP increased by 4% until the end of 2019. However, when the SARS-CoV-19 pandemic began to emerge, the Indonesian economy was negatively impacted. Indonesia is at significant risk of falling into the Middle Income Trap (MIT), and once in, it will not be easy to get out. According to the Coordinating Minister for the Economic, Airlangga Hartono, the Omnibus Law or the Job Creation Bill that the Joko Widodo 0.2 government recently passed could be a good weapon against MIT. This law is highly controversial; the effects of this reform will have a profound and lasting impact on the Indonesian economy that will last for decades. However, the Omnibus Law has been criticized. Public opinion and students for its negative impact on the rights of the environment, workers, and society.

The Middle Income Trap

The definition of Middle Income Trap or MIT is not universal; so far, no single general definition can explain its meaning. However, five main definitions can be used to understand the status of the included countries in MIT. The first is a non-empirical interpretation, based on the opinion of Gill and Kharas (2007), with MIT as a status where an economy has experienced a sharp decline in economic dynamism after successfully transitioning from low to middle-income status, presenting as stop-and-go growth, not steady long-term growth in productivity and income. Thus, it is intended to prevent the economy from moving to high levels of income.

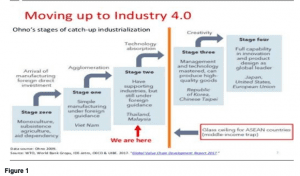

Kenichi Ohno (2009) also expressed the same opinion that a developing country must follow several phases that assimilate. This method is known as “catch-up Industrialization” or “Breaking the Glass Ceiling” (Figure 1). The approach rests on structural and economic development in which the nature of the production structure and its context is on learning and international competitiveness issues. Furthermore, according to Ohno (2009), middle-income countries face slow growth, but the analytical framework for understanding slowing growth is different and the policy prescription.

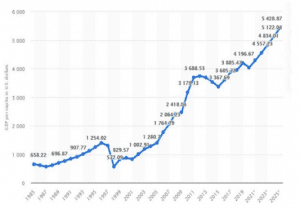

Based on Ohno’s theory, Indonesia is now in stage 2. This stage is accompanied by increased accumulation and production so that the supply of domestic spare parts and components also begins to increase (Ohno 2009: 64). It must enter from FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) and local supplies, which makes industry grow with a moderate increase in internal value, but production remains under foreign management. Another MIT interpretation is passing the income threshold, and this interpretation is the empirical interpretation of the income level as the threshold for MIT. Spence (2011) suggests that a threshold should be established through a rate of between USD 5,000 and USD 10,000 per capita income (KKB). He said this was because he saw that countries willing to transition to the level of developed countries were facing difficulties. According to the World Bank, Indonesia has entered into the middle to upper income (Table 1). This status was established following Joko Widodo’s political-economic plans during his first term. Jokowi plans to focus on infrastructure, especially bridges, highways, airports as set out in the ‘nawacita’ plan.

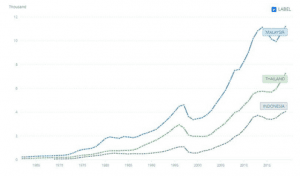

Tabel 1 : GNI rates for Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia until 2020

Source : World Bank Data

Indonesia’s status is classified as middle income because the country’s GNP has increased to $4,050 per capita. According to the World Bank, when the country’s gross national income or GNI per capita is $4,046 -$12,535, the country can enter middle to upper-income status. It can also be seen in table 1 by the World Bank. However, the path to becoming a developed country is still long and complicated, and there is a very high chance that Indonesia will be trapped in MIT. Based on the MIT theory through income threshold, middle-income countries find two threats; the first is a trap for capital income between $10,000 and $11,000, and the second the per-capita income between $15,000 and $ 16,000 trap (Eichengreen, Barry, Donghyng, Pak and Kwanho Shin, 2013).

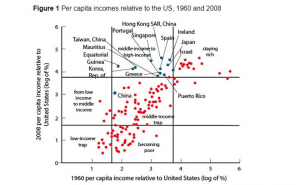

Agen and Canuto (2012) suggest that the MIT analysis must pass the catch-up benchmark, which, in MIT analysis, takes data from the relative income threshold (Figure 1)

Graph 1

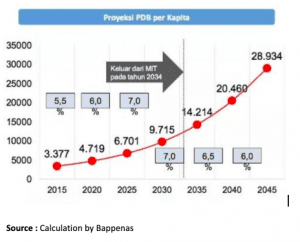

The threshold used to determine whether a country is stuck at MIT is between 5% and 45% of US GDP per capita. A study was conducted in 2012 to see how many countries have entered MIT and how many countries are high-income countries. However, this could become an example for Indonesia at present. According to Minister Bambang Brodjonegoro (2020), Indonesia will transition and enter the status of a high-income country by 2025 at the latest (Graphs 2 and 3).

Graph 2

Graph 3

Felipe, Abdon and Kumar (2012) said that countries trapped as MIT could be seen from the time threshold of 28 years for low, middle-income countries (KKB increases by 4.8% per year), and 14 years for high middle-income countries (KKB increase per year 3.5%). If these countries exceed the threshold number of years, they will be classified as trapped in MIT. However, Woo (2012) and Hawksworth (2014) conducted MIT analysis from another perspective. They analysed data from the Catch-Up Index (CUI). According to them, these countries could get stuck as MIT if they showed no inclination to meet global economic leaders from, for example, the US or China. CUI revealed that these countries enter into MIT as a result of dividing their income level: for example, based on the US income level, if Indonesias result is more than 55%, the country is classified as a high-income country, but if the result is 20% it will be called low income and or middle-income country. However, Hawksworth (2014) states that countries that want to leave MIT must follow several factors: economic stability, progress and social cohesion, technological advances, legal policies, institutional regulations, and sustainable development.

Based on this theory, it can be said that the countries included or trapped in MIT are developing countries (Pruchnik and Zowczak 2017: 18). The demographics are not favourable, especially considering the ages of the working class; if the workers are older, the saving rate will decrease compared to countries that have a younger working-class (Canning 2004, Ayiar 2013). Then, when the level of economic diversification is low, the country’s economic structure is important to continue the level towards high income. Middle-income economies must move up the value chain to maintain their high growth rates. Another consideration is inefficient financial markets, according to the World Economic Forum 2014, as they are negatively associated with a possible slowdown consisting of indicators such as availability of financial services, availability of venture capital and ease of access to loans. It also relates to inefficient raw infrastructure because the infrastructure with great quality is important in leaving MIT status (Agenor and Canuto 2012), especially based on the 2014 WEF (World Economic Forum), electricity, transportation, and communication infrastructure.

One factor that can assist a country leave MIT status is innovation. Low levels of innovation can cement a trapped state in MIT. Weak institutions can also be a problem for becoming a high-income country, especially if impacting the efficiency of the legal framework, protection of property rights, and the quality of government regulations which are important to encourage innovation and design activities.

Last but not least is an inefficient labour market and human capital. The country should make efficient use of the talents of workers, with flexibility in setting wages and hiring and firing practices.

How can Indonesia avoid being caught up in MIT? Can the Job Creation Law be a solution?

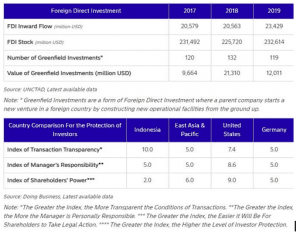

As explained above, Indonesia has become a high middle-income country. Based on the World Investment report 2020, FDI in Indonesia increased by 14% between 2018 and 2019 (figure 2).

Figure 2

Even though the Indonesian economy is developing and its status is rising, several factors can trap Indonesia in MIT status, such as high costs that can reach 60% for illegal transfers. WB has proven that the legal, economic framework is less effective than other Asian countries.

In addition, the business community generally considers the administration of justice and taxation and customs to be corrupt and arbitrary. Another factor is limited infrastructure, particularly the gap between Java and the outer or isolated islands, the unemployment rate, poverty and China’s high dependence on export commodities, thereby increasing the risk of Indonesia’s economic slowdown. Human capital in Indonesia is also one of the issues that can trap Indonesia in MIT status. Based on the latest data from the World Bank, the 2018 Human Capital Index in Indonesia is 0.53, meaning the average capacity of worker productivity is 53% of its full potential with access to education and the health system.

One of the “weapons” of the Indonesian government and Jokowi is 0.2 government is the approval of the Job Creation Law or the Omnibus Law. The Minister of Finance (Menkeu) said that she strongly agreed with the Law because, according to her, the Law will help State innovation, public creativity and various incentives to facilitate entrepreneurship in increasing income. Teten Masduki, The Minister of Cooperatives and SMEs, said that this regulation would make it easier for business actors to benefit, especially those from Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises. The Omnibus Law attempts to shorten the hyper and heavy regulatory structure in Indonesia, which, until now, has been an overlapping legal issue which is a major problem economically as it slows down competitiveness nationally. For a country like Indonesia that wants to become a country with a high income by 2035, competitiveness is important because, with fast and uncomplicated competitiveness, the investment will be more attractive to Indonesia.

The World Bank (2018) says that because Indonesia has a multi-layered structure, Indonesia is 73rd out of 190 countries and ranked 50th for competitiveness. It means that the bureaucracy in Indonesia has too many regulations, which slow down investment. Because of this problem, low human capital is increasing and also the infrastructure needs to be improved throughout Indonesia. The government has accepted the Omnibus Law because it aims to deal with vertical and horizontal public policy conflicts effectively and efficiently, harmonizing government policies at the central and regional levels, and simplifying a more integrated and effective licensing process. It is regulated into an integrated policy to break the convoluted bureaucratic chain and improve coordination between related agencies. In addition, the Omnibus Law can provide legal certainty and legal protection for policymakers.

Conclusion

The government must invest in Human Capital through education and the health and welfare system. Education is important to enable the level of knowledge and quality of society to be productive. Further, investment policies are less complicated so that foreign investors do not encounter bureaucratic difficulties. Indonesia is one of the countries with a very strong economy in Asia and the world, so the government should focus on following investment trends or trends followed by other countries, such as those focused on the green economy, infrastructure and technology. It is also important to focus on infrastructure for underdeveloped islands like North Sulawesi, Kalimantan and several areas in Sumatera. Anti-political corruption is a critical factor, as is political status in the country, which can also alter economic performance.

Indonesia has all the ingredients to become a high-income country in 2035-2040 but needs vigilance. Although the Omnibus Law is heavily criticized, it could be the last stage to move out of middle-income status, but only time will tell whether this will fail or succeed. It is necessary to focus on human capital and education, especially among the younger generation, while poverty levels must be reduced and infrastructure must be innovated, including in areas outside Java island. The bureaucracy must be facilitated, which may be facilitated by the Job Creation Law. This period is very important, as after Indonesia overcomes the COVID-19 outbreak and its economy recovers, the government needs to focus on improving domestic policies and infrastructure in under-developed areas and improve infrastructure in more developed areas such as Java.

Refrences

Agenor P., Catuno O. (2012) Middle-Income Growth Traps. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6210, The World Bank

Asia Development Bank -BAPPENAS Report (2019), Policies To support the development of Indonesia’s manufacturing sector during 2020-2024

Ayiar S, Duval R. Puy D., Wu Y., Zhang L ( 2013) Growth Slowdowns and the Middle-Income Trap IMF Working Paper WP/13/71, International Monetary Fund

Breuer, Luis E., Guajardo J., Kinda T. ( 2018), Realizing Indonesia Economic Potential, International Monetary Fund

Bukowski M., Helesiak A., Petru R., (2013) Konkurencyjna Polska 2020: Deregulacja i Innowacyjnosc. Warszawski Instytut Studiów Ekonomicznych ( WISE)

Camilla Homemo, (2019) Pengembangan modal manusia adalah kunci masa depan Indonesia, World Bank

Diemer A., Iammarino S. Rodriguez-Pose A., Storper M.; European Commission (2020), Falling Into the Middle-Income Trap? A study on the Risks for EU Regions to be Caught in a Middle-Income Trap, Final Report, LSE Consulting June 2020

Eichengreen, Barry, Donghyung, Pak and Shin Kwanho, (2013), Growth Slowdowns Redux: New Evidence on the Middle-Income Trap, NBER Working Paper, 18673, January

Faisal Basri, Gatot Arya Putra, (2016) Escaping the Middle Income Trap in Indonesia; An analysis of risks, remedies and national characteristics, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung,Jakarat, ISBN No: 978 602 8866 170

Filipe J., Kumar U., Galope R., (2014) Middle-income Transitions: Trap or Myth? Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series (421)

Gill I. Kharas H. (2007) An East Asain Renaissance, Ideas For Economic Growth, The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank

Huang B., Morgan Peter J., Yoshino N. Avoiding the middle-income trap in Asia; The role of Trade, Manufacturing, and Finance (2018), Asian Development Bank Institute

Ricca A., Rachman Lestari I. C., (2020) Omnibus Law in Indonesia: Is That the Right Strategy? Pancasila University, Jakarta -Republic of Indonesia, Advances In Economics, Business and Management Research, Volume 140, International Conference on Law, Economics and Health (2020), Atlantis Press

NN., Omnibus Law : Solusi dan Terobosan Hukum, 2019, Indonesia.go

NN “RUU Omnibus Law : Omnibus Law; Solusi dan Terobosan Hukum, diakses melalui indonesia.go

Ohno. K. (2009) The middle Income Trap, Implications for Industrialization Strategies in East Asia and Africa

Pruchnik K., Zowczak J. (2017), Middle-Income Trap: Review of the Conceptual Framework, Asia Development Bank (ABD) Institute, N 760 July 2017

Jawapos, 12/10/2020 Sri Mulyani: Omnibus Law Entaskan Indonesia dari Middle Income Trap

Woo W., Lu M., Sachs J., Chen Z., (2012) A New Economic Growth Engine for China Escaping the Middle Income Trap by Not Doing More of the Same, Imperial College Press.

World Investment report 2020; International Production Beyond the Pandemic, United Nations, New York

About the author:

Aniello Iannone is a candidate for Master of Political Science, Diponegoro University, and Junior analyst at the Institute of Analysis and International Relations (IARI).

Wives for sale! Exports of the Vietnamese Bride Industry

When it comes to Vietnamese exports, the first item that comes to mind for most people might be Vietnamese coffee. Indeed, this famous good lies among the many items exported out of Vietnam which has led to the establishment of these marketable industries. However, this article will not be exploring these conventional exports but will focus on a lesser-examined good instead- the Vietnamese bride.

This ‘economic good’ of the Vietnamese bride can be located within the larger phenomenon of the mail order bride industry. As defined by Sarker, Cakraborty, Tansuhaj, Mulder and Dogerlioglu-Demir (2013), this industry can be seen through “international marriage brokering agencies as mail order bride services”. In highlighting the centrality of brokering agencies to the market, this definition helps distinguish a bride that is specifically sold as an international ‘product’ against her fellow compatriot who marries overseas, outside of the system. Hence, this serves to demarcate and economise the human bride into a commercial good, which is arguably problematic due to its dehumanising undertones. However, for the purpose of understanding how this industry can be perceived using an economic lens of analysis, these terms will be used in the course of examination below.

Within the mail-order bride industry, countries are categorised as ‘sending’ and ‘receiving’ or exporters and importers. Developing countries, such as those in Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia, tend to be grouped as exporting countries while developed ones such as the U.S., Western Europe and East Asia are seen as importers (Lloyd, 2000). These circumstances are shaped by demand and supply factors for brides. Women facing issues of poverty in their developing hometowns become the supply while men from wealthier nations and purchasing power fuel the demand. For the brides-to-be, such marriages are a means for them to escape comparatively poor living situations with a hope to remit money gained from their new life to their families back at home. The motivation for men in these importing countries would then be to meet their needs of a wife through monetary means for reasons which do not allow them to find one in their own country (Yakushko & Rajan, 2017).

One exporting country which has become more active within this industry in recent years is the republic of Vietnam. This is due in part to the demand factor of East Asia’s economic rise which increases purchasing power and demand for the service, as well as the associating problems of changing marriage norms with more financially independent women in the region (Kim & Shin, 2008). The popularity of Vietnamese brides, in particular with these East Asian countries, can be observed in the lower cultural barriers to bridge these international counterparts. This can be seen in similarities of religion, family values and even their physique which arguably inclines them towards an East Asian model. As such, this accounts for the prevalence of Vietnam brides over mail-order brides from other destinations within the East Asian region. (Kim, 2012).

Due to the pronounced financial benefit associated with these marriages, there is a prevalent perspective that wives only seek to gain from such an arrangement. However, this article would like to highlight that this is not entirely the case. Beyond the allure of economic security lies challenges which these brides have to navigate through on their own in a foreign land after the marriage. These issues include social exclusion, higher risks of facing physical abuse within the marriage, and the threat of human trafficking when examined across the different ‘import’ countries which these brides get sent to.

In a study by Kim (2012) on Vietnamese brides in South Korea, it was found that the phenomena of social exclusion were widely faced by these ladies after migrating for their marriage. Exclusion arises from the differences that exist between the bride and the Korean society despite the overarching similarities they share compared to mail-order brides from other countries. This is especially distinct in the area of communication because the Korean society is arguably perceived to be relatively homogenous and defined by the Korean language. Difficulty in picking up the language by these brides result in them being demarcated as ‘others’ by the larger society. As a result of this, they become excluded at a societal level and the lack of acceptance makes the facilitation of integration for these brides to be difficult in finding emotional stability in their new homes.

A closer look at brides ‘exported’ to America reveal the problem of physical abuse as highlighted by Morash, Bui, Zhang, & Holtfreter (2007). A prevalence of such abuse being faced by these brides has been argued to stem from the demographics of men who tend to engage in this industry. These risk factors are seen in the larger percentage of men who have backgrounds with a history of violence that seek wives using these means. The decision to turn to women overseas is a response to the struggle in finding local women to marry due to their backgrounds. The Vietnamese bride becomes highly prized among this demographic due to their marketing as ‘subservient’ by matchmaking companies, which feeds into the notion that they are easier to control and thus appealing to such men. This however leaves the bride at the mercy of physically abusive spouses which places them in a vulnerable position.

When examined in the context of these brides in China, Barabantseva (2015) paints an even more alarming problem of trafficking that they are exposed to. Some of these brides are kidnapped, misled and sold into the market by traffickers who attempt to profit off the industry by doing so illegally instead of through official brokering agencies. This is an issue for Vietnamese brides to China in particular because of the close geographical proximity of the two where they share a common border. This is facilitated by traffickers who falsely promise Vietnamese women job opportunities in China, bringing them across the border or forcibly kidnapping them to be sold to Chinese men in need of a wife. This practice continues in recent times as reported by various news sources even in 2019 (Ng).

In conclusion, this industry is complex, dynamic and not without its benefits and challenges (Thai, 2008). From understanding the economic framework of how marriage can be commodified and facilitated in a cross-border process from Southeast Asia to the region beyond it, as well as the challenges which these brides face within this exchange, there is much which can be observed and commented on. It is hoped that even as ‘importing’ countries enjoy the benefit of being able to engage in these services, measures would be put in place to safeguard the lives of these Vietnamese brides who arrive on their shores not just an economic good but as a human.

References

Barabantseva, E. (2015). When borders lie within: Ethnic marriages and illegality on the Sino‐Vietnamese border. International Political Sociology, 9(4), 352-368. doi:10.1111/ips.12102

Kim, H. (2012). Marriage migration between South Korea and Vietnam: A gender perspective. Asian Perspective, 36(3), 531-563. doi:10.1353/apr.2012.0020

Kim, S., & Shin, Y. (2008). Immigrant brides in the Korean rural farming sector: Social exclusion and policy responses. Korea Observer, 39(1), 1.

Lloyd, K. A. (2000). Wives for sale: The modern international mail-order bride industry. Northwestern. Journal of International Law & Business, 20(2), 341.

Morash, M., Bui, H., Zhang, Y., & Holtfreter, K. (2007). Risk factors for abusive relationships: A study of Vietnamese American immigrant women. Violence Against Women, 13(7), 653-675. doi:10.1177/1077801207302044

Ng, D. (2019). Raped, beaten and sold in China: Vietnam’s kidnapped young brides. Channel News Asia. [online] Available at: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/cnainsider/vietnam-kidnapped-brides-trafficking-china-wives-11777162 [Accessed 29 Oct. 2019].

Sarker, S., Chakraborty, S., Tansuhaj, P. S., Mulder, M., & Dogerlioglu-Demir, K. (2013). The “mail-order-bride” (MOB) phenomenon in the cyberworld: An interpretive investigation. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems (TMIS), 4(3), 1-36. doi:10.1145/2524263

Thai, H. C. (2008). For better or for worse: Vietnamese international marriages in the new global economy. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press.

Yakushko, O., & Rajan, I. (2017). Global love for sale: Divergence and convergence of human trafficking with “mail order brides” and international arranged marriage phenomena. Women & Therapy, 40(1-2), 190-206. doi:10.1080/02703149.2016.1213605

Article was written by Esther Ng Shu Shan National University of Singapore.

Tourism in Singapore

Introduction

Tourism has become one of the most important global industries today. To maintain global power, Singapore has to get involve and give value to tourism in the country. Singapore can be considered a small country if you determine it from the amount of land the country has, but if you measure from its economy, it is one of the most growing counties in the world. This statement is pointed out by Hooi Hooi Leana, Sio Hing Chongb and Chee-Wooi Hooyc (2014) who say that ;

“ Tourism is a fast-growing industry in Singapore. Despite the small contribution to the country’s overall GDP, hovering around 8 percent, Singapore’s tourism industry lingers as a noteworthy showcase not only for trade and economic powerhouse but also as a hub for entertainment, media, and culture in Southeast Asia. In 2005, the Singapore Tourism Board heralded its target to ensure tourism played the role as a key economic pillar by tripling tourism receipts to S$30 billion and doubling visitor arrivals to 17 million in 2015. Besides, the “Uniquely Singapore” campaign that launched in March 2004, aimed to show the world the blend of the best of Singapore as the modern world of warm, enriching and unforgettable tourist destination had won a gold award conferred by the Pacific Asia Travel Association. In 2009, the contribution of the tourism industry on economic growth has recorded 7.3 percent and created 5.8 percent out of total employment opportunities. An increasing trend showing 4.1 percent of the total economy from the tourism industry in 2004 has escalated to 7.3 percent in 2009.”

From this fact, we can understand how tourism has had an impact on Singapore. But to understand the current impacts of tourism in Singapore, we must acknowledge what types of tourist attractions Singapore has to offer and the effects that tourism has on Singapore’s structure.

The types of tourist attractions in Singapore

Singapore can be considered one of the most outstanding counties in southeast Asia, this fact is a benefit for Singapore when it comes to tourism because Singapore’s name in more likely to pop up if you are planning a trip to this region. By recognizing this advantage, Singapore has created many noticeable tourist attractions throughout the years. Since there are so many tourist attractions in Singapore, the writer is going to narrow them down into two main categories which are nature-based tourist attractions and human-made tourist attractions. The writer plans on giving at least three destinations as examples.

Nature-based tourist attractions are tourist destinations which are more interested in the nature side of the attraction. Nature-based tourist attractions are usually combined by three elements, namely education, recreation and adventure (UK essays, 2017). Since these type of tourist attractions have little to no interventions from humans, it is the perfect type of destination for people who enjoy the natural side of life. Even though Singapore has become a very developed country, but there are still many nature-based tourist attractions around, for example, Gardens by the Bay, Botanic gardens and Sentosa island.

The first natural tourist attraction which the writer is going to mention is Gardens by the bay, a national garden and premier attraction for local and international visitors. The garden is an advanced facility which uniquely displays the plant kingdom by entertaining and educating the visitors at the same time. The garden also maintains various types of plants from all over the world. The garden can also be considered an independent organization responsible for developing and managing one of Asia’s foremost garden destinations (Gardens by the bay, n.d.). Coming to Gardens by the Bay is like being at almost every garden is the world because of the variety of plants the garden has to offer.

Another memorable nature-based tourist attraction is Botanic gardens, a collection of different types of gardens, like the Ethnobotany garden, the National orchid garden, and the Ginger garden. The gardens have played an important role in fostering agricultural development in Singapore and the region through collecting, growing, experimenting and distributing potentially useful plants. The gardens also played a key role in Singapore’s Garden City program through the continual introduction of plants of horticultural and botanical interest(Singapore botanic gardens, n.d.). Seeing all of these wonderful gardens in person can be a very relaxing experience for many people and that might be why the gardens are still famous today.

Moving on is Sentosa Island, an offshore island of Singapore accessible by a road link, cable car, and a light railway line. The island is not far from the city center (about a ten-minute drive). There have been many improvements to the island thru out the years to make sure that the island becomes a world-class tourist destination, which creates opportunities for tourists and locals. The increasing of transportation options and attractions such as a Marine Life Park and the Universal Studios Singapore amusement park have helped Sentosa island become a very popular tourist destination at an international level. But despite all of the famous human-made tourist destinations, Sentosa island has a lot of natural activities which makes the visitor want to come back for more, like Siloso beach which is perfect for a nice day on the beach. (Centre for liveable cities Singapore, 2015)

The next type of tourist attractions is human-made tourist attractions, which is any object or place that a person might travel to see which exists mainly because a human created it (BBC, n.d.), for example, Orchard Road, Singapore Flyer, Universal Studios Singapore and Chinatown.

Starting with Orchard road, one of the largest shopping, dining, and entertainment hubs in the country. Orchard Road is a 2.2 km. shopping belt between Tanglin road and Selegie road. Tourist considers Orchard road as a shopping district and prefers it to regional malls even if it may not be as close to their lodgings (Yap Yong Hwang, 2014). From becoming a popular icon for shopping in Singapore, Orchard Road has become a must-go destination for tourist in Singapore. The popularity has also helped Singapore’s economic growth.

Following up is the Singapore Flyer, which is the largest Ferris wheel in Asia. Singapore flyer can take you up to about 165 meters from ground level, which is about the hight of the 42nd floor of a skyscraper. But it is not just the hight that attracts tourist, the greatest part of Singapore flyer is the amazing view that allows you to see most of Singapore in a way you have never experienced before (Singapore tourism board, n.d.).

When mentioning about Singapore, a popular tourist attraction that comes up to mind is Universal Studios Singapore, a well-known amusement park. The park is located on Sentosa island, which is not far from the city center. This is the only Universal Studios in Southeast Asia where 28 thrilling rides and seven themed zones await (Sentosa, n.d.). The size of the park and amount of character that Universal Studios Singapore possesses easily makes it a tourist attraction that most people would want to come to at any age or gender.

The next well-known human-made tourist attraction in Chinatown, which is a must-go destination for people who visit Singapore because of its long old history and the impacts it has had on Singapore’s culture. This statement can be supported by Planning for Tourism: Creating a Vibrant Singapore (2015) which claims that ;

“In the early 1980s, Chinatown was Singapore’s top tourist attraction. An important heritage area, it was classified as a “Historic District” in the 1986 Urban Conservation Master Plan, and an “Ethnic Quarter” in the “Ethnic Singapore” thematic zone within the Tourism 21 Master Plan. It was hence a natural candidate for the pilot project on thematic development.”

The effects of tourism on Singapore’s structure

By getting an idea about what kind of tourist attractions Singapore has to offer from the previous section, the question remains that how do these tourist attractions affect Singapore’s structure? Many might argue that tourism is only a temporary income that is unpredictable, but tourism is not only about the money, it also has many aspects to offer besides money which we are going to explore in this section.

Since Singapore is a country that strongly depends on its economic structure, Singapore has made sure that they can make the best out of what they have. Many might argue that tourism has only a small part on Singapore’s economy and Singapore can easily depend on making money from music, films, concerts, fashion, computer games, architectural services, and other creative products. But the truth remains that Singapore has to strongly depend more on labor, services, and brainpower because of its lack of natural resources. So tourism is a great way to boost the economies growth because it can attribute to the provision of hard currency, creates employment opportunities and accumulates physical capital (Chew Ging Lee, 2008). The potential benefits that tourism has to offer for Singapore’s economic structure have made the government realize how important it is and got the government move involved with tourism many years ago, as reported in Tourism and economic growth: The case of Singapore (2008) that ;

“In Singapore, tourism industry receives heavy supports from its government. The Singaporean government has launched the “Uniquely Singapore” marketing campaign through Singapore Tourism Board (STB) in March 2004 in Singapore. Subsequently, this campaign was launched in the various key markets, such as in Germany in the ITB trade show on 12 March 2004. Recognizing the importance of tourism to economic activities, on 11 January 2005, Minister for Trade and Industry of Singapore unveiled the STB’s bold targets of tripling tourism receipts to S$30 billion and doubling visitor arrivals to 17 million in the year 2015. This initiative will be supported by an S$2 billion Tourism Development Fund.”

On the other hand, an uncontrolled growing economy can backfire if not handled properly. There are many possible outcomes from a growing economy that gets out of hand, such as, the increasing price of food, land, and houses which would make it very difficult for the locals to remain living where they grew up. And also depending too much on tourism as a main income might shake the economic structure when tourism is not a reliable source (UK essays, 2018).

Moving on is socio-cultural impacts that tourism has on Singapore. From the amount of tourist who comes to Singapore each year, the impacts that they have on Singapore’s society and culture are increasing by the years. By these increasements, there have been positive and negative impacts on Singapore’s socio-cultural structure due to tourism in the country.

On the positive side of socio-cultural impacts, tourism has allowed the citizens of Singapore to interact with people from all over the world. These opportunities are the gateway for exchanging ideas, knowledge, and experiences. As a result, many elements from foreign countries have combined into Singapore’s society and enhances the skills of the residents to communicate to different types of tourist and how to handle situations relating to self-expression (UK essays, 2018). Besides, tourism has encouraged Singaporeans to travel at cultural destinations in their country, for example, Chinatown. This encouragement helps Singaporeans value and understand more about their cultural history.

With the positives of the socio-cultural impacts being so significant, the downsides to Singapore’s socio-cultural is also crucial. Since there are so many tourists coming into the country each year, it becomes hard to keep in check with what everybody is doing, which can easily lead to many problems in the society like drugs and illegal activities. Another downside which comes from tourism is the fact that locals start to adapt foreign influences and westernization, which slowly changes the locals from their traditional ways and replace it with a more foreign way of life (UK essays, 2018).

Many studies have shown that tourism has increased socio-economic growth. However, tourism steered economic growth and development is achieved at the cost of environmental pollution and degradation (Muhammad Azam, Md Mahmudul Alam & Muhammad Haroon Hafeez, 2018). It can be argued that Singapore has created a few tourist attractions dedicated to improving the environment, for example, Gardens by the bay which provides a ton polluted environmental atmosphere and the NEWater plant which is one of the world’s largest water recycling facilities. These type of tourist attractions have helped promote environmental awareness, but the downsides that tourism has brought to Singapore’s environment is too critical. The limited amount of space and resources in Singapore can not handle the incoming of tourist that are coming into the country. As a result, Singapore’s environment is getting affected in many negative ways because of the limited resources to deal with environmental problems. The most noticeable negative effects on the environment are pollution from more vehicle demands, litters dropped by visitors, disturbance of natural habitats and cause damages to the landscapes, land cleared for more attractions and heavy usage of resources (UK essays, 2018).

Conclusion

Tourism has had a major impact on Singapore. Since tourism is now one of the most important global industries today, Singapore has also got on board with what tourism has to offer. Although Singapore might be a small-sized country, in terms of development Singapore is one of the highest growing counties in the world and tourism has played a key part in this success. By recognizing the strengths and weaknesses of the country, Singapore has been able to create many well-known nature-based and human-made tourist attractions, like Gardens by the Bay, Botanic gardens, Orchard Road and Singapore flyer. These extraordinary tourist attractions are the staples of Singapore’s entire tourism industry. By heavily depending on tourism as the main income, there have been many effects on Singapore’s structure. Government support has helped make a positive outcome on Singapore’s economic system and has lead to the provision of hard currency, creates employment opportunities and accumulates physical capital, but tourism might shake the economic structure when it is not a reliable source. On the socio-cultural approach, the benefits are that tourism is a gateway for exchanging ideas, knowledge, experiences and an opportunity to see value in Singapore’s culture, but the downsides are that tourism can easily lead to many problems in the society like illegal activities. Last but not least, Singapore’s environment is becoming more polluted due to the number of resources that need to be used in tourism, even though Singapore is trying as best as it can to improve and promote environmental awareness.

References

Anna Athanasopoulou. (2013, December). Tourism as a driver of economic growth and development in the EU-27 and ASEAN regions. Retrieved July 7, 2019, from http://www.eucentre.sg/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/EUCResearchBrief_TourismEU27ASEAN.pdf

BBC. (n.d.). Types of tourist attractions. Retrieved July 11, 2019, from https://www.bbc.com/bitesize/guides/zxq79qt/revision/1

CAN-SENG OOI. (2006). Tourism and the creative economy in Singapore. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://openarchive.cbs.dk/bitstream/handle/10398/6605/working%20paper%20int_can-seng%20ooi.pdf?sequence=1

Centre for liveable cities Singapore. (2015). Planning for tourism: creating a vibrant Singapore. Retrieved July 8, 2019, from https://www.clc.gov.sg/docs/default-source/urban…/plan-for-tourism.pdf

Chew Ging Lee. (2008). Tourism and economic growth: The case of Singapore. Retrieved July 8, 2019, from https://www.academia.edu/8277031/TOURISM_AND_ECONOMIC_GROWTH_THE_CASE_OF_SINGAPORE

Gardens by the bay. (n.d.). Our story. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.gardensbythebay.com.sg/en/the-gardens/our-story/introduction.html?fbclid=IwAR3KoBqclubQ4Fx9FT-df5YZQQjIItnZeGgs0sv-ypV0yYpb3aurRyZsCaI

Hooi Hooi Leana, Sio Hing Chong & Chee-Wooi Hooy. (2014). Tourism and economic growth: comparing Malaysia and Singapore. Retrieved July 9, 2019, from http://www.ijem.upm.edu.my/vol8no1/bab08.pdf

Muhammad Azam, Md Mahmudul Alam & Muhammad Haroon Hafeez. (2018, July 20). Effect of tourism on environmental pollution: Further evidence from Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand. Retrieved July 13, 2019, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652618312010

Sentosa. (n.d.). Universal Studios Singapore. Retrieved July 11, 2019, from https://www.sentosa.com.sg/en/things-to-do/attractions/universal-studios-singapore?fbclid=IwAR0-BaBMxn1bSC-tlpeOQA9dggCFKHUERhO6PybPQykifNlk2LOG5jpda8k

Singapore botanic gardens. (n.d.). The history of Singapore botanic gardens. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.nparks.gov.sg/sbg/about/our-history

Singapore tourism board. (n.d.). Singapore Flyer. Retrieved July 9, 2019, from https://www.visitsingapore.com/th_th/see-do-singapore/recreation-leisure/viewpoints/singapore-flyer/?fbclid=IwAR2Rpys70gMlDWIorssdIOOVWnLB5AEYZAu55mp74VzGXHPN5lfo68q2KZc

Tak Kee Hui & Tai Wai David Wan. (2003, March 18). Singapore’s image as a tourist destination. Retrieved July 9, 2019, from http://www.tourism.tallinn.ee/static/files/043/singapores_image_as_a_tourist_destination.pdf

Travel rave. (2013). Navigating the next phase of Asia’s tourism. Retrieved July 8, 2019, from https://www.visitsingapore.com/content/dam/MICE/Global/bulletin-board/travel-rave-reports/Navigating-the-next-wave-of-Asias-Tourism.pdf

UK essays. (2017, April 20). The nature-based attraction. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.ukessays.com/essays/tourism/the-nature-based-attraction-tourism-essay.php?fbclid=IwAR2Rpys70gMlDWIorssdIOOVWnLB5AEYZAu55mp74VzGXHPN5lfo68q2KZc

UK essays. (2018, November). SWOT Analysis of Singapore Tourism. Retrieved July 15, 2019, from https://www.ukessays.com/essays/tourism/critical-review-of-singapore-as-a-tourist-destination-tourism-essay.php

UK essays. (2018, November). Various impacts of tourism in Singapore tourism essay. Retrieved July 11, 2019, from https://www.ukessays.com/essays/tourism/various-impacts-of-tourism-in-singapore-tourism-essay.php

World travel & tourism council. (2018, March). Travel & tourism economic impact 2018 Singapore. Retrieved July 15, 2019, from https://hi-tek.io/assets/tourism-statistics/Singapore2018.pdf

Yap Yong Hwang. (2014, October 28). Orchard Road: The luxury of space. Retrieved July 11, 2019, from https://www.academia.edu/29878261/Orchard_Road_The_Luxury_of_Space?fbclid=IwAR3LhwkjPEUCuepXVMtoS_kM13wo_2DYms-QLeVmbRATvIlLcB8Kx1Pf5c8

—

This article was written by Dallas Kennamer, an undergraduate student of Psychology Department, Faculty of Liberal Arts, Thammasat University, while working as an intern at Center for Southeast Asian Social Studies (CESASS).

—

Photo by Nemanja .O. on Unsplash

Best Practice of Talent Management and Skills in Industry 4.0 Era: The Case of Banking Industry

The fourth industrial revolution, commonly known as Industry 4.0, is bringing rapid technological advancements -powered by the rise of digital technologies: cloud, big data, Internet of Things, Analytics, and Machine Learning-, changing the nature of work and increasing demand for a skilled workforce. Technology’s impact on the workforce was inevitable, adding that the most important action was responding to digital developments to optimize the workforce and its talents. Hence, industry 4.0 is rapidly transforming not only IT but business in general, particularly in terms of human-technology relationships.

The demands of the employees in industry 4.0 have been slowly transformed. Technologically-skilled labor, critical thinker, and creative labor are the most preferable employee in industry 4.0. Meanwhile, basic skills are mostly not applicable in this industry. These led to the emergence of skill gap—the gap between expertise’ needs and the capacity of the workforce. Therefore, human resources contribute to the challenges towards IR4.0 that have been threatening the global business economy. As a reference, there was a survey involving 123 Human Resource senior managers, which revealed that 70% of the problem is due to incoming worker’s poor skills, 61% Baby Boomer retirements and 51% is due to the inability to retain key talents. According to the McKinsey Global Institute, it is estimated that 49 percent of the activities that people are paid to do in the global economy has the potential to be automated by adapting currently demonstrated technology.

Besides, the employee’s skills to cope with technology automation can be varied depending on the sectors and mix of activity types. Many business sectors apply the Augmented Reality Strategy, as the effort for business sectors to apply the automation for completing the working operation. The aims are to assist and support the human’s activity. The strategy will transform how we learn, make decisions, and interact with the physical world. It will also change how enterprises serve customers, train employees, design and create products, and manage their value chains, and, ultimately, how they compete.

This writing aims to elaborate best practice of talent management and skills in the case of Banking Industry. This sector is particularly important because, banks have been relying on technology for quite some time to reduce costs, optimize processes and speed up delivery time for products and services. Banks are also feeling more pressure from clients growing expectations to offer new digital options. Banking, from the perspective of industry 4.0, calls for an even greater level of digitalization. However, Banking is also an industry which relies heavily on human resources.

For instance, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics reported by McKinsey Global Institute analysis illustrated the degree of automation potential for the various industrial sector in the US. In particular, Finance and Insurance has 43% chance to be potentially automated, comprised of management (0-10%), expertise (10-20%), interface (10-20%), unpredictable physical (10-20%), collect data (40-50%), process data (60-70%), predictable physical (90-100%).

Meanwhile, the trend in the banking industry shows that in the digital era, customers tend to utilize transaction through the digital channel. In 2011, bank customers who made transactions in e-channels in Indonesia increased by about six times. Nevertheless, previously there were only 5% to 36%. Meanwhile, starting in 2017, the customers of Mandiri mobile banking reached 37%, 17% of internet banking, and 40% ATM users. Then, the customers who visited the branch offices were only around 6%. The changing pattern of business service highly depends on digital transformation, which affects the activity of human capital. However, industry 4.0 increase the level of competitiveness, and the possibility of the talent market in the global economy. For instance, globalization and issues of IR 4.0 have enabled talented employees not to limit the marketing of their skills within one region, but they can look for jobs in firms across the world with digital skill. Because of this, experts are mainly worried about the possibility of intense global competition for talents which may draw attention towards how talent is recruited, retained, developed and managed yet, the uncertainly of industrialization of 4. 0.

Despite the advancement of technology in Industry 4.0, human capital remains an important element to run the business sector. Hence, how banking creates effective talent management to ensure that employees can make use of their talent to achieve an absolute success of a business?

Besides, talent management and skill in industry 4.0 are closely linked to human-technology relationships. The idea behind talent management is built on the fact that business is run by people. Therefore, putting the right people in the right job positions is what constituted a good talent management and for future need. The employability, knowledge, and competence are indicators of talent which determine the success of a business. Talent identification and development help business in identifying employees that later been develop as a leader of the future that represents the combination of a cyber-physical system due to the diversification of Industry 4.0.

There are two main steps of mostly bank industry to manage talent management and skill in the fourth industrial revolution. Firstly, talent management should start with the business strategy and what signifies talent towards a business. Employee as a potential resource is the source of the influence of an organization because the employee moves the business. Also, vice versa, moving the business means having to move employee with competitive strategy.

The strategy is also needed to understand the know-how the business’s goals are achieved. The bank industry understands that employees move the business. Thus, in some reasons, banking sector prepares the employee candidates or newly employed to have a deep understanding regarding the business’s goal.

Secondly, it is important to enhance and maintain the skills of new and existing employees through training, career development, commitment, and rewards. The recruitment and selection of employees in finding talented employees to an appropriate position by providing an effective training program. Career development is a lifelong learning process that continuously adds work experience. The positive relationship to job satisfaction and retain employees increased productivity and performance of the business sector. Meanwhile, employee hopes to get a reward for what they have contributed to an organization; therefore rewards affect the performance of every employee and affect their commitment. Commitment is interdependent with emotions because employees need physical and emotional support.

Conclusion

The management of advanced technology still depends on human capital. The case of the banking industry illustrates that the significant role of human capital is to drive business move. Therefore, the competition of the global economy in Industry 4.0 relies on human’s skills and creativity to manage the digital transformation to reach organization’s success. In this regard, a certain incentive given by the business sector is significant to enhance and maintain employee’s performance. Indeed, the fourth industrial revolution does not always pose the risk of job loss. This article opens the upcoming research on how the comparison of each banking industry in Indonesia improves their performance perpetually towards Industry 4.0.

—

This article was written by Archita Nur Fitrian, an undergraduate student of International Relations Studies at the Universitas Gadjah Mada, while working as an intern at Center for Southeast Asian Social Studies (CESASS).

—

Photo by Erol Ahmed on Unsplash

The Impacts of the Fourth Industrial Revolution on Higher Education in ASEAN

The fourth industrial revolution or 4IR builds on the digital revolution and combines multiple technologies that are leading to significant shifts in the economy, business, society, and individually. It is characterized by a fusion of technologies that is blurring the lines between the physical, digital, and biological spheres. In practice, it is the idea of smart factories in which machines are augmented with web connectivity and connected to a system that can visualize the entire production chain and make decisions on its own. (Schwab, 2016)

According to Schwab, the fourth industrial revolution is not only changing the “what” and the “how” of doing things but also “who” we are, what it means to be human. It also includes the transformation of entire systems, across and within countries, companies, industries, and society as a whole. (Schwab, 2016)

Up to recent days, we have faced three phases of industrial revolution. Firstly, began with steam and water. Then, electricity and assembly lines discovered. After that, computerization started in 1969. Nowadays, even though there is not an exact period yet, we are entering the discourse of the fourth industrial revolution coming with more advanced technology.

Every industrial revolution provided positive and negative impact to our society. One of the major impacts that we have experienced in the last industrial revolution was the employment issue. It is not only about the job losses but also transformation of the nature of the works. This would be the grave issue in the ongoing (upcoming) industrial revolution. It is predicted as much as 47% of jobs may be automated away in the future. Moreover, 65% of children entering primary school today will have jobs in categories that don’t yet exist. (World Economic Forum, 2017)

Currently, in ASEAN, the top main job family is farming, fishing, and forestry. Looking at the current job family in this region plus the economic and digital technology development, one question arises, has ASEAN entered the fourth industrial revolution yet? I would argue that ASEAN is still in the stage of third industrial revolution. But however, the revolution happening in the other part of the world, will surely affect ASEAN. A report on The Future of Jobs from the World Economic Forum found that the 4IR will lead to a net loss of over 5 million jobs in 15 major developed and emerging economies. Therefore, ASEAN has to adjust to survive in the changing global world.

As the fourth industrial revolution comes with the more advanced technology, ASEAN needs to prepare the upcoming workers with the compatible skills and educations. Many scholars suggest the developing countries investing in areas such as STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education as the future jobs will be mostly related to those areas.

Data on the Human Capital Report by World Economic Forum showed that the distribution of the degree holders in ASEAN has bigger number in social and humanities area. Universities in ASEAN produced only 24% STEM-related graduates (5% in science, 19% in engineering, manufacturing, construction). Therefore, for ASEAN to be more competitive in the 4IR, ASEAN needs to risen the number of students studying in STEM education.

This situation is not only faced by ASEAN but also the US. For a comparison, in the US alone there are more than 500,000 open technology jobs, but universities produce only 50,000 science graduates each year. Therefore, there is a gap between the demand and supply of labour to be solved globally.

To solve this problem in general, the business sector and academia need to sit together and discuss about the future of jobs in the 4IR to minimize the gap between supply and demand of future labour market. What universities could do is to reconsider and reshape the curriculum to respond the changing environment of works to prepare the graduates with the precise skills and educations needed in the future. In the other side, business sector needs to study what are the criteria of jobs in the future and discuss it with the higher education institution. But however, from the study done by World Economic Forum, it appears that business actors do not believe that these technologies will have advanced significantly enough by the year 2020 to have a more widespread impact on global employment levels.

University is a place to educate people for the purpose of knowledge and enlighten people. However, higher education is also one of the main actors globally in reducing the disadvantage that the 4IR might cause. Universities are key platforms to prepare the future workers and also to educate people to keep the revolution in track to benefit all. And that every university can have a direct role in creating economic opportunity for millions of people by reshaping the current curriculum for existing and potential talent to adapt with the ongoing change.

The 4IR will create jobs disruption. Therefore, there will be discrepancy between the demand and supply of the future labour market. Higher education as the bridge to the working environment is seen as one of the main stakeholders in preventing the great loss (jobs) that might cause. Business sector and academia need to discuss together to solve this problem. In ASEAN, it is suggested to increase the number of students studying in the STEM education as the 4IR will demand more human capital in science and technology. Besides, higher education in ASEAN also needs to rethink and reshape the current curriculum to prepare graduates in tune with the change that the 4IR brings. Generally, both business and academia need to cultivate a lifelong learning in every individual to adapt and adjust with the upcoming changes.

—

This article was written by Walid Ananti Dalimunthe from the ASEAN Studies Forum.

Tackling Migration Issues: Does Indonesia Provide Adequate Legal Protection to Refugees and Asylum Seekers?

In the midst of the global refugee crisis, there has been much discussion regarding the management of refugees and asylum seekers in the developed world, however, this issue has been somewhat overlooked in Indonesia. Historically, Indonesia has been utilised as a transit country, due to its geographical location, archipelago geography, and bureaucratic functioning. This trend has continued in recent years – in 2016, approximately 13,829 refugees arrived in Indonesia. However, whilst Indonesia may still be characterised as a transit country, this reality is quickly changing, particularly as both Australia and the United States, two primary re-settlement nations, have decreased their refugee intake. In 2016, 761 refugees were resettled to the US, and 347 to Australia, almost a 50% decrease in settlement from the previous year. A drop in re-settlement rates, coupled with an inevitable increase in re-settlement waiting periods, has contributed to the transformation of Indonesia’s role as a country that merely acts as a place of transit, to a destination where refugees are now spending a significant amount of time. Given these circumstances, the need for a more robust solution in the Government’s approach and attitude towards refugees has become evident.

It should be no surprise that a strong legal protection system is critical to allow for the long-term provision of essential rights such as access to health, education and financial sovereignty. The 1951 UN Convention on the status of refugees, and the 1967 protocol, are the primary international instruments governing refugee rights, management and processing, however, Indonesia is not yet a signatory to these instruments. Although Indonesia’s most recent legal instrument pertaining to refugees, the Presidential decree 125 of 2016, does provide some clarity regarding the status of refugees and asylum seekers in Indonesia, the decree is still largely limited in its scope, and fails to provide sufficient guidance on refugee rights, an issue that is becoming increasingly vital, given the current decline in re-settlement rates amongst refugees who have reached Indonesian shores. Furthermore, as Sophie Duxson, research assistant at the Renata Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law at UNSW, discusses, the status and influence of the decree, given that it is not a law, and thus cannot be constitutionally reviewed by an Indonesian court, is also questionable.

International Law