The Movement of Restoring Film Industry in Cambodia by Teng Athipanha

Introduction

Film, as a source of entertainment and escapism, has played a crucial role throughout history. It serves beyond mere enjoyment, aiding in reconciling with the past, preserving traditions, and expressing national identity. During the twentieth century, the introduction of film in Southeast Asia varied across countries, primarily through colonial contact driven by various European powers, which significantly impacted the film industry. It has brought the introduction of technology to Southeast Asia, which marked the inception of a local film industry. Films began to incorporate local languages, music, settings, and actors, gradually gaining popularity among the local audience (Ang, 2021). Despite initial developments, certain countries experienced downfall periods that erased progress. Cambodia, notably affected by the painful political history of the Khmer Rouge invasion, faced considerable challenges, including the film business.

The industry, which started in the 1950s and flourished during the “golden age” of the 1960s, suffered a severe blow after the fall of Phnom Penh to the Khmer Rouge, with many films stolen, destroyed, or lost. As a result of the lack of dynamism, the road to reconstructing the film industry has been very challenging.

Nevertheless, there has been recent growth in the film industry. Many filmmakers have striven to produce films of excellent quality from a technical aspect and conceptual standpoint, where they have explored new creative areas and a wider range of plots. This effort has been a great step thus far; even though there have been difficulties, there is still a lot of hope for the process of reviving the golden age.

This paper aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how Cambodia’s film industry has evolved over the years amidst challenges and opportunities. It will examine the history and efforts to revive it, along with the difficulties faced along the way, highlighting the industry’s significant steps toward a comeback.

Body

As mentioned earlier, colonial interactions played a pivotal role in introducing film to Southeast Asia. This marked a significant turning point in the regional film industry, facilitating the emergence of cinema and fostering a sense of local identity (Ang, 2021). For instance, films began to incorporate local languages, settings, and another cultural component (Ang, 2021). Like other countries in the region, Cambodia transformed cinema into a medium that resonated personally with audiences. This transformation ushered in the ‘Golden Era’ from the 1950s to the 1960s This era is defined by a period of remarkable significance and success, with its understanding deeply rooted in the accomplishments of that time within the industry.

The emergence of this era can be attributed to colonial contact. Furthermore, the contributions of pioneering filmmakers also play important role, including Roeum Phon, Eav Ponnakar, and Som Sam Al (Raksmey, 2023). These filmmakers, pursued their studies abroad, and had involved in the creation of the early Cambodian-produced films (Raksmey, 2023). According to Borak, many of these narratives incorporated with Khmer folktales, such as Puthisean Neang Kong Rey or the legend of Chao Srotop Chek (Raksmey, 2023).

Unfortunately, this era was short-lived due to the devastating Khmer Rouge invasion, which inflicted widespread harm, including the film industry. Many important social figures, including actors and filmmakers from the 1960s and 1970s, were killed as a result of their communist ideology and attempts to establish a classless agrarian society. Additionally, a considerable number of film and prints were lost, stolen, or destroyed during this period. Therefore, the industry has to rebuild from scratch, journey which fraught with challenges. After the Khmer Rouge regime was overthrown, the industry began to slowly recover, with “My Mother is Arb” specifically contributing to the horror genre (Raksmey & Raksmey, 2023). Following that, the VHS became the primary shooting tool for a large number of movies. Even though it made it possible for more production companies to make more films, the drawback became more and more obvious, especially as production values dropped and there were fewer producers with expertise. Moreover, it has also been criticized for its inability to convey its own identity and be engaging due to its struggle and adherence to a predetermined narrative (RICHARDOT, 2013).

Distribution is another challenge, as filmmakers often struggle to recover their production costs due to a poorly structured market and the absence of an established intellectual property policy. Most films are distributed on home video rather than in theaters. VCDs are widely accessible on the market and are less expensive than theater tickets (Richardot, 2013). According to Ung Nareth, president of the Motion Picture Association of Cambodia, purchasing a new DVD at a retail price of even $7 is considered expensive for many Cambodians (Styllis, 2014). Therefore, as the informal market structure expands, it creates the image of the acceptability of the pirate business, which is very harmful to the industry.

Despite these challenges, the industry has seen progressive transformation in recent years, fueled by technological advancements and creative exploration by filmmakers. More filmmaker began to enhancing conceptual perspective and diversifying plotlines. Traditionally, film narratives often centered around genres like romance, horror, comedy, and folktale. In the recent year, however, Cambodia has achieved a milestone by producing its first-ever Sci-Fi film, namely ‘’Karmalink’’. It was collaboration of local filmmaker Sok Visal as a co-producer, who was directed by American Jake Wachtel. It was produced outside of traditional studio systems (Raksmey, 2023). The focus was more on artistic expression and cultural representation through the combination of Buddhist concepts and AI narrative components (Raksmey, 2023). Furthermore, there are also some film production and non-profit organization that has involve and support the new generation of filmmaker as well as fostering talented actor/actress.

- AntiArchive is the film productions that has been producing independent films, with the goal of encouraging viewers to rethink the relationship of films and filmmakers with the past and history. Diamond Island, one of their notable film, was premiered at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival Critic’s Week and earned the SACD Prize

- The Acting Academy is a non-profit organization located in Phnom Penh, providing free training to young Khmer actors. Additionally, they invites expert coaches and lecturers to offer these aspiring actors and actresses the opportunity to explore various acting techniques.

Apart from that, there have been efforts to showcase local films to a global audience. Leak Lyda, the CEO of LD Film Production, noted his initiatives in his work, such as the horror film “12E,” for which they also created an English dubbed version targeting international viewers (Nou, 2023). Besides that, he also recently did a collaboration in the comedy film “Rent Boy” which featured Myanmar actor Paing Takhon alongside Cambodia’s 2022 Miss Grand Cambodia winner, Pich Vatey Saravathy, in the lead female role (Nou, 2023). While it is not the first time Cambodian actors have shared the screen with international stars, this progress shows a growing optimism about the potential for local films to gain exposure on the international stage.

To sum up, in attempt of restoring this sector has revealed a growth potential. It is thanks to the determined efforts of emerging talents, organizations, and filmmakers. What’s more, not only that it raises hopes of a return to the golden era but also going beyond it. Not to mention, with recent collaborations with foreign filmmakers, can bring fresh perspectives that would enhance the industry. This, in turn, has the potential to inspire the next generation of young filmmakers, fostering a brighter future for Cambodian cinema.

References:

- Ang, J. (2021, November 17). Unpacking history through Southeast Asian films. Smu.edu.sg. https://research.smu.edu.sg/news/2021/nov/17/unpacking-history-through-southeast-asian-films

- Raksmey, H., & Raksmey, H. (2023, October 18). Cambodia’s cinematic history reflects trends, changing landscapes. Asia News Network. https://asianews.network/cambodias-cinematic-history-reflects-trends-changing-landscapes/

- Raksmey, H. (2023, October 26). Cambodia’s cinematic history reflects trends, changing landscapes. Www.phnompenhpost.com. https://www.phnompenhpost.com/lifestyle/cambodias-cinematic-history-reflects-trends-changing-landscapes

- RICHARDOT, S. (2013, February 13). Cinema Reborn | A Profile of Cambodian Films. ASEF Culture360. https://culture360.asef.org/insights/cinema-reborn-profile-cambodian-films/

- Styllis, G. (2014, March 29). Cambodia Lags in Fight Against Intellectual Property Piracy – The Cambodia Daily. The Cambodia Daily. https://english.cambodiadaily.com/news/cambodia-lags-in-fight-against-intellectual-property-piracy-55193/

- Raksmey, H. (2023, February 13). Cambodia’s first sci-fi film coming soon to cinemas. Www.phnompenhpost.com. https://www.phnompenhpost.com/lifestyle/cambodias-first-sci-fi-film-coming-soon-cinemas

- ANTI ARCHIVE. (2014). About us. https://www.antiarchive.com/about.html Théâtre | Daro Zucco par The Acting Academy. (2019). Institutfrancais-Cambodge.com. https://institutfrancais-cambodge.com/theatre-roberto-zucco-par-the-acting-academy/#/

- Nou, S. (2023, August 23). CAMBODIA’S CO-PRODUCTION REVOLUTION. Www.linkedin.com; Kongchak. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/cambodias-co-production-revolution-kongchak

Author:

Teng Athipanha (Intern at CESASS UGM)

What the Mekong mean for Security in Southeast Asia: Hydro-Hegemony and Food Insecurity, or Cooperation by Thomas Robert Bartley

Southeast Asia is a region developing and expanding fast in terms of population, importance, and interconnectedness. While the future beckons promisingly for the continued success of the region, potential backsliding into instability threatens to change this trajectory. Non-traditional aspects of security now take the forefront of issues threatening this backsliding. While changes in the balance of power between Southeast Asian nations or the efficacy of institutions remain integral to the region’s future, threats like a warming and unpredictable climate or breaches in cyber-security now have the potential to drastically change the state of security in the region.

The issue with perhaps the most disruptive potential is that of food security. While this largely has been considered an issue or goal of development studies, its impact on the security of nations is now being recognised as significant. Studies conducted for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) show striking patterns of correlation between rising food prices and the emergence of disruption and conflict. This can range from spikes in anti-government sentiment and irregular migration, to the outbreak of civil conflict and upticks in participation in rebel movements and organised crime., Disruptions to the affordable and ready access to food will inevitably have severe impacts on the stability of any country. Reporting from Foreign Policy summates this idea in stating that lack of food security will have ‘serious implications for global political stability’, and that it could lead to ‘mass displacement as people migrate to more arable [regions] in search of stable food supplies’.

The ability of food insecurity to destabilise at the individual level as well as the national and international levels is what makes this threat particularly dramatic. Within the Southeast Asian region, food security is increasingly being cited as a cause for concern. According to recent indexing produced by The Economist, the region, not including Singapore, ranks 1.3 points below the global average., This ranking has the potential to deteriorate significantly given concerns for the long-term agricultural productivity in the region. Aside from sheerly security concerns, the risk also is also compounded by economic dimensions as import-export balances and national income are affected by reductions in agricultural production, requiring a higher reliance on foreign markets.

The area of most concern within Southeast Asia is the potentially exponential deterioration of production depending on the Mekong River System. As the river flows through Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Myanmar, deterioration in the system would represent a significant issue afflicting Southeast Asia as a whole. The river currently discharges an estimated 475 cubic kilometres of fresh water annually, feeding a delta of 795,000 km2 in size. The benefits of this flow are felt to such an extent that the river is sometimes referred to as the ‘mother of waters’, reflecting its importance to the lives of tens of millions of people.

Deteriorations in the river system are a particular concern for the Mekong Delta region of Vietnam and the Tonle Sap region of Cambodia. The former of these regions is responsible for 90% of the rice exports of Vietnam and the livelihoods of 17 million people, whilst the collapse of the later would define Cambodia as a failed state., On current trajectory, Laos and Cambodia are predicted to be unable to match domestic production with domestic demand by 2030. While these events would cause significant harm and displacement for the people of these countries, the effects of this contingency would inevitably spill across borders, potentially causing sharp increases in food prices and reductions in food availability throughout Southeast Asia. This undoubtedly would be felt in conjunction with other economical or security concerns that go along with having increasingly insecure neighbours.

This issue takes particular relevance given current developments afflicting the Mekong. As the river crosses through multiple nations, many issues persist around shared management of the system. Here, unilateral decisions, especially those like the damming of the river, are a particular cause for concern. These developments can have drastic impacts for downstream productivity. In particular, projects such as damming are seen to have a substantial impact on sediment deposits and water availability for downstream populations. This makes agricultural yields in any given area harder to predict, hurting the ability of small-scale farmers to plan for the future, and making agricultural investments seem riskier. Additionally, increasing rates of glacial melt at the sources of the river in the Tibetan Plateau further complicate the issue by causing seasonal flows to become increasingly erratic. While these developments may be approached and mitigated through the use of effective multilateral action, there are strong incentives for some states to resist concerted action, or to otherwise seek benefit from their geographic positioning at the detriment of other regional players.

In explaining why this may be the case, considering how cooperation on this issue is incentivised or disincentivised provides a road map for current patterns of behaviour. When it comes to the issue of increasing rates of glacial melt, the reasoning behind lack of effective action is similar to lethargies affecting other environmental issues. That is, as the phenomenon is caused by increasing carbon emissions globally, the attribution of blame or responsibility becomes difficult, hindering effective approaches to the issue. The cost of action would also be high, likely requiring significant systemic change with no promise of reciprocation from other stake holders. However, costs of inaction could verge on being catastrophic. A UNESCO report states that the glaciated regions of Asia are the fastest receding in the world. The report estimated that the water requirements of over a billion people are met by these glaciers. In South Asia alone, increased rates of melt are expected to affect well over 177 million people in terms of income and livelihood.

As most Southeast Asian nations are positioned geographically far from the glaciated areas feeding the Mekong, it will however remain difficult to direct regional attention to the issue. East and South Asian countries positioned relatively closer to the sources of the river may have a greater role to play in initiating dialogue and coordinated responses. Considering that the health of the Mekong is integral to the futures of some Southeast Asian nations, such actions would signify a great deal of regional responsibility and forward thinking on the part of instigating nations. This may entail the creation of water sharing agreements, information sharing initiatives, and memorandums of understanding regarding norms and expectations of behaviour which affects the river. An appreciation of the spill-over effects of food insecurity and broader regional malaise is required in order to make such decisions. This would come as an alternative to potential zero-sum thinking pursued through conventional geopolitics. While there are areas of concern that South-Eastern Mekong states should act upon (like unsustainable activities or overuse of the Delta), responsibility for a large amount of the river’s health lies with upstream states.

The greatest present risk to the future productivity of the region is the feared ‘sinking of the Mekong’. The Delta’s land mass (primarily located in Vietnam) is sustained through constant flow of sediment from upstream, mentioned earlier. Because of this, any alterations to these flows will impact the total land mass available for productive activities. While decreasing flows from glaciers may impact this in the future, more immediately impactful is the development of damming projects in upstream states. At the date of writing, these dams are primarily located in China with some beginning to appear in Laos. The eight currently finished damming projects have already affected around 50% of the usual sediment flows. If additional damming projects are completed as planned, sediment deposits will be restricted by more than 96% of their current levels. Such development of the river also has the potential to restrict migratory fish and their breeding patterns, further harming productivity of downstream fisheries. Fishermen in the region already express worries about the future of their wellbeing, lamenting the change in their catch from only a decade earlier.

The substantial impacts of this damming can point to potentially callous disregard for water and food security on the part of upstream states. The impacts on Vietnamese and Cambodian productive regions in particular point to large absences in regional responsibility especially as it regards policy actions from Beijing. Current publications note the effect of the Mekong’s damming to be excessive, potentially leading to complete inundation of the Mekong Delta by the turn of the century. This phenomenon will occur as the rate of sediment deposit is eventually exceeded by rates of sea-level rise; it is likely this will be accompanied by a salination of the delta, limiting agricultural and fishery productivity to a fraction of current levels. This could become a direct cause of failure for food security in two Southeast Asian nations, with certain ramifications for surrounding countries. The pursuit of energy security on the part of the Chinese state is noted, however, the benefits of these projects may quickly lead to the emergence of a flashpoint in the region. Calls from lower Mekong states to cease the damming have become louder in recent years, especially from the sub-state level. Hearing and responding to these calls is likely to bring higher levels of sustained benefit for Beijing.

The falsification of Chinese led narratives, however, prompts speculation that the behaviour is likely to be unyielding. With regards to Mekong damming, one article published by China’s Global Times is titled: ‘from being responsible neighbour to biodiversity protection vanguard’. The article criticises the prevalence of ‘Western media outlets … bashing Chinese hydropower stations, claiming that the Chinese stations at upstream of Mekong River are responsible for aggravating droughts in downstream countries’. In response to this criticism, the outlet instead claims Chinese hydropower projects have a positive role to play in flood mitigation and biodiversity promotion. This is in stark contrast with facts on the ground, where substantial flooding in Cambodia is directly attributable to the dams.

In South Asia, this pattern of behaviour is mirrored. A recent ‘super hydropower’ damming project proposed by Beijing on the Brahmaputra River also points to an apparent disregard for consequence. The project has stoked fears in India regarding declines in the availability of water in the productive regions of the river basin. The seeming disregard for these concerns has led commentators to point to the potential goal of ‘hydro-hegemony’ being pursued by the Chinese state. In commenting on the prospects of damming Asian rivers, The Diplomat notes the potential for the management of transboundary river systems to be influenced by ‘the greater socio-political context’ existing between nations. By this it is meant that there are potentially strong incentives for transboundary systems to be wielded as a tool of geopolitical leverage.

However, while the presence of transboundary rivers may exacerbate tensions, they may also be used to facilitate cooperation on a greater level. The common good of the river systems and associated environmental goods can provide a tangible source of shared responsibility. Philip Hirsch, a commentator on the region, points to this dichotomy of potential outcomes in stating that ‘perhaps in no other arena is the conflation of geopolitics with the environmental agenda as significant as in the case of transboundary river basins.’ Given the potentially disastrous effects on non-cooperation, particularly as caused through the use of damming for hydroelectric purposes, the Mekong may provide a decisive focal point for shared dialogue and future relations. Whether or not these relations provide positive dividends depends on the self-awareness of nations, and the impacts they desire to have on the region in which they reside.

Regional cooperation based around the environments of South and Southeast Asia have the potential to create a road map to future cooperation. The development of the Hindu-Kush Himalayas is overseen by a group of South and Central Asian nations (HKH countries), and the lower Mekong is, to an extent, regulated by the Mekong River Commission. The variable in this situation is whether Beijing will engage effectively in regional dialogues or exclude itself so that it may continue to act with impunity. At this current point in time, it appears as though China’s long standing ‘non-participation, non-discussion, non-recognition’ attitude is taking the lead. This strong-arming approach to regional issues misses the point of cooperation in this instance; the outcome of participation is not compromising the nation’s power, but rather seeking assurance of stability in its neighbourhood. Leveraging natural resources may reap dividends in the medium-term but it is inevitable that this will create a messy operating environment in the future. The Mekong can provide a gathering point by which nations can initiate dialogue and work towards mutually beneficial outcomes. That being said, if Beijing insists on asserting a ‘rights to territorial sovereignty’ mentality it may achieve hydro-hegemony at the cost of food security, human security, and a rapidly deteriorating regional security environment.

Bibliography

Articles:

- Biemans, C. Siderius, A.F. Lutz, S. Nepal, B. Ahmad, T. Hassan, W. von Bloh, R.R. Wijngaard, P. Wester, A.B. Shrestha & W.W. Immerzeel 2019. ‘Importance of Snow and Glacier Meltwater for Agriculture on the Indo-Gangetic Plain’. Nature Sustainability. Vol. 2. pp.594-601

- M. Kondolf, R. J. P. Schmitt, P. A. Carling, M. Goichot, M. Keskinen, M. E. Arias, S. Bizzi, A. Castelletti, T. A. Cochrane, S. E. Darby, M. Kummu, P. S. J. Minderhoud, D. Nguyen, H. T. Nguyen, N. T. Nguyen, C. Oeurng, J. Opperman, Z. Rubin, D. C. San, S. Schmeier & T. Wild 2022. ‘Save the Mekong From Drowning’. Science. vol. 376. pp.583-585

- Brochmann, N. P. Gleditsch 2012. ‘Shared Rivers and Conflict – A Reconsideration’. Political geography. vol. 31. pp.519-527

- Hirsch 2016. ‘The Shifting regional Geopolitics of Mekong Dams’. Political Geography. vol. 51. pp.63-74

Phan, L 2016, ‘The Sambor Dam: How China’s Breach of International Law Will Affect the Future of the Mekong River Basin’, The Georgetown Environmental Law Review, vol.32, no. 105, p.107

Reports:

The Economist Group, Corteva Agriscience 2022. ‘Global Food Security Index 2022’. p.3-7 The Economist Group. London.

UNESCO, IUCN 2022. ‘World Heritage Glaciers: Sentinels of Climate Change’. p.18 UNESCO, Paris. IUCN, Gland.

Journalistic Sources:

Foreign Policy. ‘The Global Food Crisis is Here’, Jason Hickel, viewed 1st December. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/08/21/the-global-food-crisis-is-here/

Radio Free Asia. ‘Despite Seasonal Floods Now, Experts See Risk of Mekong Drying Up’, Dan Southerland, viewed 5th December. https://www.rfa.org/english/commentaries/mekong-threats-09132019155403.html

The Diplomat. ‘The Precarious State of the Mekong’, Nicholas Muller, viewed 5th December. https://thediplomat.com/2022/11/the-precarious-state-of-the-mekong/

NBC News. ‘Chinese Dams on Mekong River Endanger Fish Stocks, Livelihoods, Activists Say’, Keir Simmons, Rhoda Kwan, Nat Sumon & Jennifer Jett, viewed 5th December. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/chinese-dams-mekong-river-endanger-fish-stocks-livelihoods-activists-say-n1288720

Global Times. ‘A Glimpse of China’s largest Hydroelectric Project Along Lancang River: from being Responsible Neigbor ro Biodiversity Protection Vanguard’, Zhao Yusha & Cao Siqi in Pu’er, viewed 7th December. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202209/1276056.shtml

The Diplomat. ‘China’s Super Hydropower Dam and fears of Sino-Indian Water Wars’, Genevieve Donnellon-May, viewed 12th December https://thediplomat.com/2022/12/chinas-super-hydropower-dam-and-fears-of-sino-indian-water-wars/

Author: Thomas Robert Bartley (Intern at CESASS UGM)

The Discrimination Towards Indigenous Women in Cultural Practices by Medyline Agnes Elias

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) adopted in 1948 by the international community,proved that human rights were being accepted as universal norms that needed to be respected, protected, and promoted. The phrase in the UDHR “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” means that everyone is equal in claiming their rights without distinction. This is supported by the first paragraph of the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Actions preambular, where it recognizes human rights as a universal norm by stating that “All human rights are universal, indivisible and interdependent and interrelated.” UDHR as a foundation of international treaties later became the foundation of other international human rights instruments including Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). The existence of CEDAW in international law marks the importance of protection and promotion of women’s rights and gender equality between men and women, but in the process of gender equality to some women it is more challenging especially to women from minority communities, like indigenous women. Report from the United Nation (UN) special rapporteur on violence against women by Reem Alsalem stated that indigenous women and girls experienced systematic discrimination in indigenous and non-indigenous justice system (United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 2022). Furthermore, the Human Rights Committee in their General Comment No. 28, art. 3 highlight that the inequality of the enjoyment of rights by women is deeply embedded in tradition, history and culture including religious attitudes.

UDHR ensures that everyone including indigenous women deserve equal rights, art. 1 and 7 of UDHR contain the principle of equality and non-discrimination, and in art. 2 of UDHR prohibits any kind of distinction on the fulfillment of human rights on the basis of sex. Prohibition of discrimination on the basis of sex can also be found in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) art.2 and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) art. 3. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women art. 3 stated that “Women are entitled to equal enjoyment and protection of all human rights and fundamental freedom in the political, economic, social, culture, civil or any other field..”, the enjoyment and protection of rights mentioned in art.3 including the right to equality, the right to be free from all forms of discrimination.

Culture has two sides in human rights aspects, it can be the reason for human rights violation, but it can also protect human rights. A report of a special rapporteur, Farida Saheed on enjoyment of cultural rights of women on an equal basis with men in 2012 stated that there are many practices and norms in society that discriminate against women and it is justified by culture, religion and tradition. Leading experts also stated that social groups mostly suffered human rights violations in the name of culture (Celorio, 2022, pp. 320-231). 75 years since the universal norms of human rights were established and 42 years since CEDAW was instituted, these norms and rights are still not applicable to some indigenous communities because of their cultural beliefs. The reality of equality of human rights to women and men are different in the context of indigenous people. The importance of culture is often mentioned in the establishment of international law, but there is still a gray area of cultural practice and women’s rights.

In Maluku there are the Nualu indigenous people, who are one of many examples of indigenous people in Indonesia. Nualu is an indigenous community located in Seram Island, Maluku. Women’s position in Nuaulu’s social system is considered lower than men, this is because in Nualu, women are considered dirty due to experiencing menstruation. Posune is a local culture from generation to generation in Nuaulu where women who are menstruating or about to give birth are sequestered in a house called Posune. Posune is located on the side or back of the main house. Posune is a forbidden area for men, if a man approaches or enters the Posune even though it is empty it is considered a sin and will be subject to sanctions in the form of being ostracized from the community and in the form of fines set by the customary head. Posune applies to unmarried women and married women. A married woman in the Nuaulu community when she is menstruating she is not allowed to have physical contact with her husband, on the other hand the woman is allowed to cook for her husband, but is not allowed to deliver it directly to her husband. Women in the social system of the Nuaulu community cannot become leaders even if they have menopause, women can only help but are not allowed to sit in positions. The Nuaulu customary system has been passed down from generation to generation, stipulating that women should not become leaders of men (Nina, 2012).

The culture and traditions of Nualu indigenous communities according to international human rights norms violates the rights of women and violates the principle of non-discrimination and universal human rights law. UDHR recognizes that everyone deserves equal rights, but the international community also recognizes indigenous people and their collective rights. The establishment of Indigenous and Tribal People Convention 1989 marked the recognition of indigenous people and tribunal people by the international community. These international instruments created antinomy on the fulfillment of women’s rights and gender equality because on the otherside international community recognize the universal human rights norms, but also recognize indigenous people traditions and culture. This antinomy departs from two perspectives in human rights law theories, namely universalism and cultural relativism. These two theories contradict each other so that there is debate among scholars about these two theories.

The theory of universalism asserts that every human being has certain human rights because they were born as a human being and it made them inherit human rights. Universalism theory believes that human rights are something that cannot be taken away and are intended to protect human dignity. Universalism theory views that human rights are universal and so must be owned by everyone on the basis of equality is not a controversial matter. The theory of universalism can be found in UDHR (Donders, 2010, pp. 16). Unlike the view of universalism theory, the theory of cultural relativism sees that there is cultural diversity that exists everywhere in the world, including views about right and wrong. This view makes cultural relativism theory assume that universal human rights do not exist and the existence of cultural diversity means that an understanding of human rights can be interpreted differently (Donders, 2010, pp. 16).

The debate between scholars about universalism and cultural relativism has divided the scholars into those who support universalism and those who deny universalism. The debate of these two theories started in the second UN World Conference on Human Rights in 1993. The debate has been going around on universal human rights norms as a western values that have been forced to non-western countries (Cerna, 1994, pp. 740). The debate of universalism and cultural relativism also depart from women’s rights (Higgins, 2017, pp. 97). Those who support cultural relativism argue that feminism is a product of western ideology and global feminism is a form of western imperialism. Cultural relativists argue that the conception of human rights by the universalist ignores the collective rights of indigenous and tribal people (Charters C, 2016, pp. 12). In Asia, the universality of human rights concepts face challenges because of private rights. These private rights related to religion, culture, the status of women, the right to marry and to divorce and to remarry, the protection of children, family planning (Cerna, 1994, pp. 744, 746). The conflict between universal human rights principles and cultural relativism often happen in Africa, Asian, and Islamic values. To address this differential issue scholars like Renteln, Donders, and Donelly proposed a way to reconcile the differences between universalism and cultural relativism which are flexibility in interpretation and implementation of rights, cross-cultural dialogue, and focusing on the process and the actors involved (Vleugel, 2020, pp. 41).

To strengthen the scholars’ opinion on how to address the difference of those two theories, we have to consider the role states play in these issues. CEDAW contains the national effort the state should take to maintain gender equality. Art 2(f) of CEDAW mentions for states “to take all appropriate measures, including legislation, to modify or abolish existing laws, regulations, customs and practices which constitute discrimination against women ” and art. 5(a) of CEDAW requires states to modify the social and cultural patterns that discriminate against women. Human Rights Committee (HRC) on general comment No. 28 stated that state have the obligation to ensure human rights enjoyment of all individuals and to ensure that states should to all the necessary steps these steps include “…removal of obstacles to the equal enjoyment of such rights, the education of the population and of State officials in human rights, and the adjustment of domestic legislation so as to give effect to the undertakings set forth in the Covenant. The State party must not only adopt measures of protection, but also positive measures in all areas so as to achieve the effective and equal empowerment of women. “. In art. 3 of ICESCR also highlighted states obligation to ensure the equal rights of men and women. In general comment No. 28 paragraph 32 it might or might not giving us an answer to the debate between universalism and cultural relativism in the aspect of culture and indigenous women’s rights by stating that “The rights which persons belonging to minorities enjoy under article 27 of the Covenant in respect of their language, culture and religion do not authorize any State, group or person to violate the right to the equal enjoyment by women of any Covenant rights, including the right to equal protection of the law. “.

In conclusion, states have the obligation to respect indigenous people culture, tradition, and their collective rights, but also states have the obligation to make an effort to protect indigenous women’s human rights from any violation and discrimination including from the practice of traditions and culture. States playing important rules in the nexus of women’s rights and culture. Universalism is important in protecting individual rights, and cultural relativism is important in protecting collective rights. Human rights practice shouldn’t overlook the fulfillment of individual and collective rights. States should take appropriate action in fulfillment of individual rights of indigenous women’s rights while respecting the collective rights of indigenous people. The protection of all individuals, including indigenous women’s human rights, depends on the state’s political will. The international human rights instruments will not be effective if there is no political will from states.

REFERENCES

Book

Celorio, R. (2022). Women and International Human Rights in Modern Times: A Contemporary Casebook. Women and International Human Rights in Modern Times: A Contemporary Casebook (pp. 1–354). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800889392.

Nina, Johan. (2012). Perempuan Nuaulu: Tradisionalisme dan Kultur Patriarki. Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia.

Vleugel, V. (2020). Human Rights and Cultural Diversity. Between and Beyond Universalism and Cultural Relativism. In Culture in the State Reporting Procedure of the UN Human Rights Treaty Bodies: How the HRC, the CESCR and the CEDAWCee use human rights as a sword to protect

Journal

Cerna, C. M. (1994). Universality of human rights and cultural diversity: implementation of human rights in different socio-cultural contexts. Human Rights Quarterly, 16(4), 740–752. https://doi.org/10.2307/762567.

Charters, C. (2016). Universalism and Cultural Relativism in the Context of Indigenous Women’s Rights. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2887711.

Donders, Y. (2010). Do cultural diversity and human rights make a good match? International Social Science Journal, 61(199), 15–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2451.2010.01746.x.

Higgins, T. E. (2017). Anti-essentialism, relativism, and human rights. In Challenges in International Human Rights Law (Vol. 3, pp. 53–88). Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315095905.

Internet

United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. (2022) , End Violence Against Indigenous Women and Girls: UN Expert. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/06/end-violence-against-indigenous-women-and-girls-un-expert. Accessed March 28th 2023.

Legal Instruments

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)

Vienna Declaration and Programme of Actions

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

Human Rights Committee General Comment No. 28

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women

Author:

Medyline Agnes Elias (Intern at CESASS UGM)

Can Indonesia Get Out of The Middle-income Trap: Policy Analysis

Introduction

With a population of 260 million people, Indonesia is the fourth largest country globally and one of the most dynamic economies in the global market. According to the World Bank, Indonesia is now included in the status of a middle-income country. The economy in the country is running smoothly, especially during the last decade following the economic contraction caused by the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998. Due to its fairly rapid economic development, Indonesia has become a developing country and the first economic power in Southeast Asia. Its role in ASEAN continues to be important. Indonesia’s political and economic structure has changed over the years since its independence. In 1950, after the end of Dutch colonialism, economic and political development focused on the agricultural sector to realize a self-sufficient agricultural system by 1960. In the middle of 1970-1980, after the crude oil price fell, the Indonesian economy rapidly developed with urbanization and industrialization programs, for This Indonesia occurred as a consequence of the political change from crude oil exports to manufactured exports.

After the Soeharto regime and the financial crisis in 1998-1999, Indonesia’s economy and politics progressed rapidly, and by 2004-2008 the GDP increased by 5%. During 2008-2009, the slowing down of the global economy did not have a high impact on the Indonesian economy, but GDP increased by 4% until the end of 2019. However, when the SARS-CoV-19 pandemic began to emerge, the Indonesian economy was negatively impacted. Indonesia is at significant risk of falling into the Middle Income Trap (MIT), and once in, it will not be easy to get out. According to the Coordinating Minister for the Economic, Airlangga Hartono, the Omnibus Law or the Job Creation Bill that the Joko Widodo 0.2 government recently passed could be a good weapon against MIT. This law is highly controversial; the effects of this reform will have a profound and lasting impact on the Indonesian economy that will last for decades. However, the Omnibus Law has been criticized. Public opinion and students for its negative impact on the rights of the environment, workers, and society.

The Middle Income Trap

The definition of Middle Income Trap or MIT is not universal; so far, no single general definition can explain its meaning. However, five main definitions can be used to understand the status of the included countries in MIT. The first is a non-empirical interpretation, based on the opinion of Gill and Kharas (2007), with MIT as a status where an economy has experienced a sharp decline in economic dynamism after successfully transitioning from low to middle-income status, presenting as stop-and-go growth, not steady long-term growth in productivity and income. Thus, it is intended to prevent the economy from moving to high levels of income.

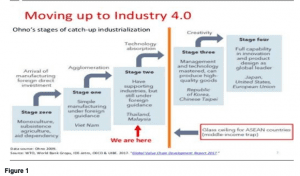

Kenichi Ohno (2009) also expressed the same opinion that a developing country must follow several phases that assimilate. This method is known as “catch-up Industrialization” or “Breaking the Glass Ceiling” (Figure 1). The approach rests on structural and economic development in which the nature of the production structure and its context is on learning and international competitiveness issues. Furthermore, according to Ohno (2009), middle-income countries face slow growth, but the analytical framework for understanding slowing growth is different and the policy prescription.

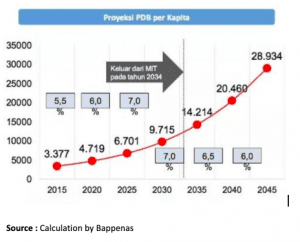

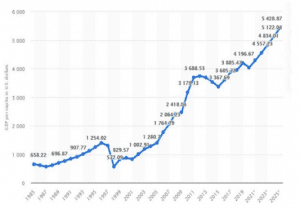

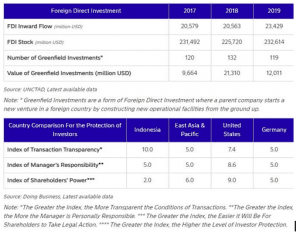

Based on Ohno’s theory, Indonesia is now in stage 2. This stage is accompanied by increased accumulation and production so that the supply of domestic spare parts and components also begins to increase (Ohno 2009: 64). It must enter from FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) and local supplies, which makes industry grow with a moderate increase in internal value, but production remains under foreign management. Another MIT interpretation is passing the income threshold, and this interpretation is the empirical interpretation of the income level as the threshold for MIT. Spence (2011) suggests that a threshold should be established through a rate of between USD 5,000 and USD 10,000 per capita income (KKB). He said this was because he saw that countries willing to transition to the level of developed countries were facing difficulties. According to the World Bank, Indonesia has entered into the middle to upper income (Table 1). This status was established following Joko Widodo’s political-economic plans during his first term. Jokowi plans to focus on infrastructure, especially bridges, highways, airports as set out in the ‘nawacita’ plan.

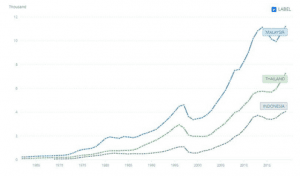

Tabel 1 : GNI rates for Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia until 2020

Source : World Bank Data

Indonesia’s status is classified as middle income because the country’s GNP has increased to $4,050 per capita. According to the World Bank, when the country’s gross national income or GNI per capita is $4,046 -$12,535, the country can enter middle to upper-income status. It can also be seen in table 1 by the World Bank. However, the path to becoming a developed country is still long and complicated, and there is a very high chance that Indonesia will be trapped in MIT. Based on the MIT theory through income threshold, middle-income countries find two threats; the first is a trap for capital income between $10,000 and $11,000, and the second the per-capita income between $15,000 and $ 16,000 trap (Eichengreen, Barry, Donghyng, Pak and Kwanho Shin, 2013).

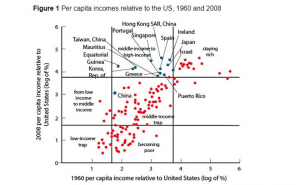

Agen and Canuto (2012) suggest that the MIT analysis must pass the catch-up benchmark, which, in MIT analysis, takes data from the relative income threshold (Figure 1)

Graph 1

The threshold used to determine whether a country is stuck at MIT is between 5% and 45% of US GDP per capita. A study was conducted in 2012 to see how many countries have entered MIT and how many countries are high-income countries. However, this could become an example for Indonesia at present. According to Minister Bambang Brodjonegoro (2020), Indonesia will transition and enter the status of a high-income country by 2025 at the latest (Graphs 2 and 3).

Graph 2

Graph 3

Felipe, Abdon and Kumar (2012) said that countries trapped as MIT could be seen from the time threshold of 28 years for low, middle-income countries (KKB increases by 4.8% per year), and 14 years for high middle-income countries (KKB increase per year 3.5%). If these countries exceed the threshold number of years, they will be classified as trapped in MIT. However, Woo (2012) and Hawksworth (2014) conducted MIT analysis from another perspective. They analysed data from the Catch-Up Index (CUI). According to them, these countries could get stuck as MIT if they showed no inclination to meet global economic leaders from, for example, the US or China. CUI revealed that these countries enter into MIT as a result of dividing their income level: for example, based on the US income level, if Indonesias result is more than 55%, the country is classified as a high-income country, but if the result is 20% it will be called low income and or middle-income country. However, Hawksworth (2014) states that countries that want to leave MIT must follow several factors: economic stability, progress and social cohesion, technological advances, legal policies, institutional regulations, and sustainable development.

Based on this theory, it can be said that the countries included or trapped in MIT are developing countries (Pruchnik and Zowczak 2017: 18). The demographics are not favourable, especially considering the ages of the working class; if the workers are older, the saving rate will decrease compared to countries that have a younger working-class (Canning 2004, Ayiar 2013). Then, when the level of economic diversification is low, the country’s economic structure is important to continue the level towards high income. Middle-income economies must move up the value chain to maintain their high growth rates. Another consideration is inefficient financial markets, according to the World Economic Forum 2014, as they are negatively associated with a possible slowdown consisting of indicators such as availability of financial services, availability of venture capital and ease of access to loans. It also relates to inefficient raw infrastructure because the infrastructure with great quality is important in leaving MIT status (Agenor and Canuto 2012), especially based on the 2014 WEF (World Economic Forum), electricity, transportation, and communication infrastructure.

One factor that can assist a country leave MIT status is innovation. Low levels of innovation can cement a trapped state in MIT. Weak institutions can also be a problem for becoming a high-income country, especially if impacting the efficiency of the legal framework, protection of property rights, and the quality of government regulations which are important to encourage innovation and design activities.

Last but not least is an inefficient labour market and human capital. The country should make efficient use of the talents of workers, with flexibility in setting wages and hiring and firing practices.

How can Indonesia avoid being caught up in MIT? Can the Job Creation Law be a solution?

As explained above, Indonesia has become a high middle-income country. Based on the World Investment report 2020, FDI in Indonesia increased by 14% between 2018 and 2019 (figure 2).

Figure 2

Even though the Indonesian economy is developing and its status is rising, several factors can trap Indonesia in MIT status, such as high costs that can reach 60% for illegal transfers. WB has proven that the legal, economic framework is less effective than other Asian countries.

In addition, the business community generally considers the administration of justice and taxation and customs to be corrupt and arbitrary. Another factor is limited infrastructure, particularly the gap between Java and the outer or isolated islands, the unemployment rate, poverty and China’s high dependence on export commodities, thereby increasing the risk of Indonesia’s economic slowdown. Human capital in Indonesia is also one of the issues that can trap Indonesia in MIT status. Based on the latest data from the World Bank, the 2018 Human Capital Index in Indonesia is 0.53, meaning the average capacity of worker productivity is 53% of its full potential with access to education and the health system.

One of the “weapons” of the Indonesian government and Jokowi is 0.2 government is the approval of the Job Creation Law or the Omnibus Law. The Minister of Finance (Menkeu) said that she strongly agreed with the Law because, according to her, the Law will help State innovation, public creativity and various incentives to facilitate entrepreneurship in increasing income. Teten Masduki, The Minister of Cooperatives and SMEs, said that this regulation would make it easier for business actors to benefit, especially those from Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises. The Omnibus Law attempts to shorten the hyper and heavy regulatory structure in Indonesia, which, until now, has been an overlapping legal issue which is a major problem economically as it slows down competitiveness nationally. For a country like Indonesia that wants to become a country with a high income by 2035, competitiveness is important because, with fast and uncomplicated competitiveness, the investment will be more attractive to Indonesia.

The World Bank (2018) says that because Indonesia has a multi-layered structure, Indonesia is 73rd out of 190 countries and ranked 50th for competitiveness. It means that the bureaucracy in Indonesia has too many regulations, which slow down investment. Because of this problem, low human capital is increasing and also the infrastructure needs to be improved throughout Indonesia. The government has accepted the Omnibus Law because it aims to deal with vertical and horizontal public policy conflicts effectively and efficiently, harmonizing government policies at the central and regional levels, and simplifying a more integrated and effective licensing process. It is regulated into an integrated policy to break the convoluted bureaucratic chain and improve coordination between related agencies. In addition, the Omnibus Law can provide legal certainty and legal protection for policymakers.

Conclusion

The government must invest in Human Capital through education and the health and welfare system. Education is important to enable the level of knowledge and quality of society to be productive. Further, investment policies are less complicated so that foreign investors do not encounter bureaucratic difficulties. Indonesia is one of the countries with a very strong economy in Asia and the world, so the government should focus on following investment trends or trends followed by other countries, such as those focused on the green economy, infrastructure and technology. It is also important to focus on infrastructure for underdeveloped islands like North Sulawesi, Kalimantan and several areas in Sumatera. Anti-political corruption is a critical factor, as is political status in the country, which can also alter economic performance.

Indonesia has all the ingredients to become a high-income country in 2035-2040 but needs vigilance. Although the Omnibus Law is heavily criticized, it could be the last stage to move out of middle-income status, but only time will tell whether this will fail or succeed. It is necessary to focus on human capital and education, especially among the younger generation, while poverty levels must be reduced and infrastructure must be innovated, including in areas outside Java island. The bureaucracy must be facilitated, which may be facilitated by the Job Creation Law. This period is very important, as after Indonesia overcomes the COVID-19 outbreak and its economy recovers, the government needs to focus on improving domestic policies and infrastructure in under-developed areas and improve infrastructure in more developed areas such as Java.

Refrences

Agenor P., Catuno O. (2012) Middle-Income Growth Traps. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6210, The World Bank

Asia Development Bank -BAPPENAS Report (2019), Policies To support the development of Indonesia’s manufacturing sector during 2020-2024

Ayiar S, Duval R. Puy D., Wu Y., Zhang L ( 2013) Growth Slowdowns and the Middle-Income Trap IMF Working Paper WP/13/71, International Monetary Fund

Breuer, Luis E., Guajardo J., Kinda T. ( 2018), Realizing Indonesia Economic Potential, International Monetary Fund

Bukowski M., Helesiak A., Petru R., (2013) Konkurencyjna Polska 2020: Deregulacja i Innowacyjnosc. Warszawski Instytut Studiów Ekonomicznych ( WISE)

Camilla Homemo, (2019) Pengembangan modal manusia adalah kunci masa depan Indonesia, World Bank

Diemer A., Iammarino S. Rodriguez-Pose A., Storper M.; European Commission (2020), Falling Into the Middle-Income Trap? A study on the Risks for EU Regions to be Caught in a Middle-Income Trap, Final Report, LSE Consulting June 2020

Eichengreen, Barry, Donghyung, Pak and Shin Kwanho, (2013), Growth Slowdowns Redux: New Evidence on the Middle-Income Trap, NBER Working Paper, 18673, January

Faisal Basri, Gatot Arya Putra, (2016) Escaping the Middle Income Trap in Indonesia; An analysis of risks, remedies and national characteristics, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung,Jakarat, ISBN No: 978 602 8866 170

Filipe J., Kumar U., Galope R., (2014) Middle-income Transitions: Trap or Myth? Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series (421)

Gill I. Kharas H. (2007) An East Asain Renaissance, Ideas For Economic Growth, The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank

Huang B., Morgan Peter J., Yoshino N. Avoiding the middle-income trap in Asia; The role of Trade, Manufacturing, and Finance (2018), Asian Development Bank Institute

Ricca A., Rachman Lestari I. C., (2020) Omnibus Law in Indonesia: Is That the Right Strategy? Pancasila University, Jakarta -Republic of Indonesia, Advances In Economics, Business and Management Research, Volume 140, International Conference on Law, Economics and Health (2020), Atlantis Press

NN., Omnibus Law : Solusi dan Terobosan Hukum, 2019, Indonesia.go

NN “RUU Omnibus Law : Omnibus Law; Solusi dan Terobosan Hukum, diakses melalui indonesia.go

Ohno. K. (2009) The middle Income Trap, Implications for Industrialization Strategies in East Asia and Africa

Pruchnik K., Zowczak J. (2017), Middle-Income Trap: Review of the Conceptual Framework, Asia Development Bank (ABD) Institute, N 760 July 2017

Jawapos, 12/10/2020 Sri Mulyani: Omnibus Law Entaskan Indonesia dari Middle Income Trap

Woo W., Lu M., Sachs J., Chen Z., (2012) A New Economic Growth Engine for China Escaping the Middle Income Trap by Not Doing More of the Same, Imperial College Press.

World Investment report 2020; International Production Beyond the Pandemic, United Nations, New York

About the author:

Aniello Iannone is a candidate for Master of Political Science, Diponegoro University, and Junior analyst at the Institute of Analysis and International Relations (IARI).

The Development of Jokowi’s plan; why the Omnibus Law is good for the economy but a threat to civil rights in Indonesia

Jokowi’s first development plan: infrastructure

Joko Widodo, better known as Jokowi, is in his second period of the presidency in Indonesia, which had, during his first period, he concentrated policy on the development of the Indonesian economy, especially through investment in the development of the development infrastructure (Hill and Negara 2019). Jokowi knows that infrastructure has been the “Achilles Heel” for developing countries like Indonesia, yet he focused on investment, health systems, and education during his second term. The last law on labour, the Omnibus law, was confirmed by the Jokowi administration last October during the COVID-19 pandemic. The new law will administer labour, environmental and investment regulation (Arifin 2021, Mahy 2021)

Nevertheless, what will be the cost-benefit of this decision? Time will tell whether the Omnibus law will have a good effect or a dangerous effect. However, the people did not see any good in this new government choice, as evidenced by responses from the labour and student movements and academics. A strong infrastructure is essential for the effective functioning of the economy, particularly for reducing economic gaps in the region and reducing the poverty rate. (Firework World Economic Forum 2014).

Comparing the last year of the Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono presidency with the start of the Jokowi period, the stark difference in approaches to economic development is clear. The first act that Jokowi did was to end the fuel subsidy, a subsidy that cost the Government 17.8 billion $ in 2014 and 4.8 billion $ in 2015, enough to divert to a start in promoting the infrastructure, improving the health system, and education ( Negara 2016). Indeed it was already clear that Jokowi planned to dedicate priority to infrastructure investment in the draft of the Medium Term National Development Plan or in Indonesian language RPJMN 2014-2019, where the Government hoped to increase 7 % GPD starting in 2016 (RPJMN report 2014). However, the anticipated GDP target was not reached. Instead, the GDP of Indonesia has grown just 4 /5 % YoY during the slowdown of the global economy created by the COVID-19 pandemic.

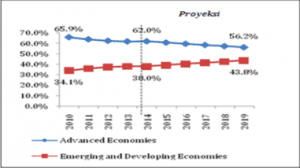

Nonetheless, Jokowi wanted Indonesia to be more economically independent, also not wanting Indonesia to fall behind other countries in Asia like India, China, and Vietnam where infrastructure was developing apace. During his first semester, according to BAPESSAN analysis, no longer Europe and America, but Asia and the Pacific would be the centre of the world economy (Graphic 1).

Graphic 1 demonstrated the prediction made by BAPESSAN.

Source : Bappenas, Oxford Economic Model

Furthermore, Jokowi had understood that the national balance was insufficient without investment from foreign sources, based on investment in infrastructure. Jokowu also knew that, compared with other developing countries like Vietnam or China, Indonesia has a slow and complex bureaucratic system, especially for the legacy of foreign investment. These factors have combined to push the Government to create the controversial new Omnibus Law, cutting many bureaucratic knots in investment to the environment and labour laws.

In this scenario, Jokowi has understood that without foreign Investment, Indonesia cannot develop faster. After the end of Yudhoyono’s period and the start of Jokowi’s period, the budget that Indonesia needed for investment in infrastructure was 300 billion US$, yet the national public finance of Indonesia afforded just 20% of that amount (Deny Sidharta and Jared Heath 2014). According to Hall Hill and Negara (2019), one of the challenges in meeting Indonesia’s massive investment in infrastructure ambition is the weak tax system causing the government shortfalls in the public reserve. Therefore there were a few associated challenges that the Jokowi administration needed to resolve. The first was financing, and the others were land clarity, planning and projecting (Utomo 2017). In addition, Jokowi also faced another huge problem from entrenched local corruption festering through years of power decentralism after the end of the Suharto regime ( Nugroho 2020). In combination, tax inflation, excessive bureaucracy, and massive corruption have pressured Jokowi to accelerate the Omnibus Law to fix his plan to develop the nation’s economy.

The Omnibus Law: worker, gender, environment rights

During the emergence of COVID-19 in Indonesia, the Jokowi Government and The House of Representatives accelerated the procedure for acceptance of the new Omnibus Law on labour in Indonesia to repair the bureaucracy that has, according to the President of Indonesia Joko Widodo (2020), slowed down investment in the country. The problems that made Jokowi create the Omnibus Law were hyper-regulation and bureaucratic knots (Anggraeni, Rachman 2020). According to the Regulatory Quality Index ranking, Indonesia is on the lowest level. Another problem is the decentralisation of power that has increased corruption at the local level (Johannes Nugroho 2020) and slowed down investment procedures. However, the effects on workers, gender, indigenous affairs and the environment are worrying.

Many scholars and NGOs have demonstrated their disappointment to the Government. The Omnibus Law is associated with profound adjustment to legislation that otherwise presents obstacles to investment, including the revision of 79 laws, reorganisation of legislation into 11 clusters and adjustments to more than 1000 articles, including those impacting labour law, social law, and national social security agency law (Amnesty International 2020). Many protections from the 2003 labour legislation have been deleted or modified. A new law on wages and job security is considered a threat, specifically because it does not consider inflation rates for the minimum wage. Therefore is revokes the set city district minimum wage. In practice, without inflation and cost living criteria for determining the minimum wage, poor areas like Papua are further weakened with not enough income to cover the daily cost of living (Usman Hamid 2020).

Another issue of concern is the relative security of the worker when signing a job contract. Under the Omnibus Law, employers cannot offer a permanent job contract but can provide a temporary contract for an indefinite period, meaning that the worker can more easily lose their job. The review of Labour Law presents a new threat with the possibility of performing “work for free”, meaning extra work that does not produce income for the worker. Moreover, article 93 (2) of the Labour Law does not allow for paid time off during menstruation, which is a significant violation of women’s rights.

Additionally, there is concern from environmental NGOs that the new law will increase deforestation in Indonesia (Madani 2020). There is a possibility that by 2056, 5 areas of Indonesia, Riau, Jambi, Sumatra, Bangka Belitung and Center Jawa, will lose their natural forest. Article 29,30,31 of the new law retains the AMDAL (environmental impact assessment requirements) but deletes the function of an independent committee composed of NGOs and activists for the environment. The new law further supports deforestation to increase the palm oil plantation, a dangerous threat that the Government has endorsed with the amplification of the work. It will probably negatively affect the local people who live in the areas that will be deforested, particularly art. 50 (2) sentences 12A and 17B prohibit farming in forestry areas and commercial activities in unregistered forests (Hamid and Hermawan 2020). How to report the NGO Human Rights Wacht (HRW), this is a violation of international norms, such as those expressed in the ICESCR and the UN declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples (HRW 2020 )

On the one hand, the Omnibus Law was created by the Jokowi administration to push ahead with infrastructure and economic development through investment. The new Labour Law attempts to remove excessive bureaucratic administration and red tape relating to foreign investment regulation, liberalizing all foreign investor businesses in any sector, except for currently heavily regulated, banned or illegal industries such as weapons or illicit drugs (Shen and Siagian 2020). The Labour Law also brings tax reforms, an extremely complex issue because tax evasion is one of the highest in the region. The Omnibus Law aims to reduce the tax to 20% for private companies and 17% for Indonesia-listed companies, while foreign workers will be exempt from paying personal income tax on income derived outside Indonesia (Shen and Siagian 2020). On the other hand, the Omnibus Law potentially damages workers’ rights, especially women and indigenous workers, so while investment may grow, the price will be paid by erosion in democracy and civil rights.

Refrences

Anggraeni,R, Rachman, C.I . (2020). Omnibus Law in Indonesia: Is That the Right Strategy?, Atlantis Press, Advances In Economic, Business and Management Research, volume 140 https://doi.org/10.2991/aebmr.k.200513.038

Amnesty International. (2020) Commentary on the labor cluster of the Omnibus Bill on Job Creation ( RUU CIPTA KERJA) Jakarta, Index: ASA 21/2879/2020

Amnesty International. (2020) Omnibus Bill on Job Creation Poses “Serious Threat” to Human Rights,

Amnesty International. (2020) Submission to United Nations committee on the elimination of discrimination against woman

Arafin, S. (2021), Illiberal Tencencies in Indonesia Legislation:te case of the omnibus law on job creation. The Theory and Practive of legaslation Juornal, Vol 9 N.o 2 https://doi.org/10.1080/20508840.2021.1942374

Bland B. (2020), Man of Contradictions, Joko Widodo and the struggle to remake Indonesia, Lowy Institute, Penguin Random House Australia

BAPPENAS, Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah 2014-2019

Breuer L.E, Guajardo J, Kinda T. (2018) Realizing Indonesia’s Economic Potential, International Monetary Fund (IMF)

Emont J. (2016) Visionary or Cautious Reformer? Indonesia President Joko Widodo’s Two Years in Office https://time.com/4416354/indonesia-joko-jokowi-widodo-terrorism-lgbt-economy/

Firduas F. (2020) Indonesia Fear Democracy is the Next Pandemic Victim, Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/04/indonesia-coronavirus-pandemic-democracy-omnibus-law/

Hamid. U., Ary (2020). Hermawan, Indonesia’s Omnibus Law is a bust for human rights, New Mandala. https://www.newmandala.org/indonesias-omnibus-law-is-a-bust-for-human-rights/

Hill H, Negara S.D. (2019) ; The Indonesia Economy in Transition, Policy challenge is Jokowi era and beyond, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute

Human Rights Watch. (2020) Indonesia; New Law Hurts Workers, Indigenous Groups, Massive Omnibus Bill Passed Little Public Consultation. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/15/indonesia-new-law-hurts-workers-indigenous-groups

HRW Ihanuddin, Krisiandi. (2020) Jokowi Ungkap Alasan RUU Cipta Kerja Dikebut di Tengah Pandemi, Kompas.com

Negara D. (2016 ) Indonesia’s Infrastructure Development Under The Jokowi Administration, Southeast Asian Affairs, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute

Nugroho J. (2020) Indonesia’s Omnibus Law won’t kill corruption , The Lowy Institute. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/indonesia-s-omnibus-law-won-t-kill-corruption

Madani (2020) . Tinjuan Risiko RUU CIPTA kerja terhadap hutan alam dan pencepain komitmen iklim Indonesia. https://madaniberkelanjutan.id/2020/05/06/tinjauan-risiko-ruu-cipta-kerja-terhadap-hutan-alam-dan-pencapaian-komitmen-iklim-indonesia

Mahy,P. (2021) Indonesia ‘s Omnibs Law on Job Creation: Reducing labour Protections in a Time of Covid-19, Monash Business School, Monash University, Labour, Equality and Human Rights Research Gruop Working Paper N.o 23

Mighty Earth. (2020) Indonesia’s Omnibus Bill Approval Poses Dire Threat to Anti-Deforestation Efforts. https://www.mightyearth.org/2020/10/05/indonesias-omnibus-bill-approval-poses-dire-threat-to-anti-deforestation-efforts/

Shen,J.,Siagian,C. (2020). Indonesia‘s Omnibus Law: A magic wand amidst a global pandemic? https://singaporeglobalnetwork.gov.sg/stories/business/indonesias-omnibus-law-a-magic-wand-amidst-a-global-pandemic/

Sidharta D, Jared Heath. (2014) Building Effective Partnerships, Jakarta Post

World Economy Forum (2014) The Global Competence Index 2014-2015 www.weforum.org/gcr.

Utomo, Wahyu. (2017). Tentang Pembangunan Infrastruktur di Indonesia. kppip.go.id.

About the Author:

Aniello Iannone is a candidate for Master of Political Science, Diponegoro University, and Junior analyst at the Institute of Analysis and International Relations (IARI).

Inklusi Sosial di Era Digital (Social Inclusion in the Digital Age)

Abstrak

Pola relasi-relasi sosial yang tumbuh dan berkembang dalam kehidupan komunitas digital antara lain ditandai oleh kontak langsung, komunikasi yang melibatkan banyak orang (many-to-many communication), keterbukaan pandangan (ide), serta kebebasan berinteraksi. Uraian berikut memetakan perbedaan pandangan tentang dampak pola relasi-relasi tersebut terhadap inklusi sosial atau proses meningkatnya kapasitas akses komunitas pada sumber daya (resources), menguatnya partisipasi mereka dalam formulasi dan eksekusi keputusan publik, serta jalinan kerja sama di antara mereka dalam memanfaatkan dan menciptakan peluang. Di satu sisi, terdapat pandangan yang yakin (optimistic) bahwa relasi-relasi sosial tersebut memiliki dampak signifikan terhadap inklusi sosial karena mampu menghimpun perbendaharaan informasi yang dapat dipergunakan sebagai saluran akses pada sumber daya (resources), dapat dimanfaatkan sebagai pengetahuan (knowledge) untuk menciptakan dan memanfaatkan peluang, serta sebagai sarana mendorong partisipasi politik. Sementara itu, di sisi yang lain, terdapat pandangan yang justru meragukannya (skeptic) karena relasi-relasi sosial tersebut masih menghadapi kendala ketimpangan digital (digital divide) dan literasi sehingga tidak kondusif bagi upaya meningkatkan inklusi sosial.

Kata kunci: informasi, akses, inklusi, ketimpangan digital

Pendahuluan

Kemajuan teknologi informasi dan komunikasi telah mengubah berbagai tatanan kehidupan. Kita sekarang hidup di era digital atau era informasi, sebuah kehidupan yang diwarnai oleh relasi-relasi sosial yang melembagakan kontak secara langsung, komunikasi yang melibatkan banyak orang (many-to-many communication), keterbukaan pandangan (ide), dan kebebasan berinteraksi. Relasi-relasi sosial tersebut didukung oleh komputer (computer mediated) dengan beragam divice melalui e-mail, chat room, short message service, video call, telepon, teks, dan gambar, yang mampu menembus batas wilayah geografis, kelas, etnis, agama, gender, dan ideologi, juga membentuk. Di samping itu, keanggotaan komunitas digital bersifat sukarela (voluntary) dan terjalin atas dorongan atau motivasi pribadi (individuated) serta tidak mengenal hubungan hierarkis (berlapis). Berbeda dengan kehidupan komunitas nyata (real), relasi-relasi sosial dalam komunitas ini tidak terdapat dominasi individu atau kelompok atas individu atau kelompok lain. Identitas dalam komunitas ini juga bersifat fleksibel dan dibangun secara spontan. Identitas dalam komunitas ini tidak dibangun berdasarkan penghargaan status dan peran sebagaimana lazim terdapat dalam kehidupan komunitas nyata. Oleh karena itu, setiap anggota komunitas ini dalam waktu yang sama bisa menjadi follower (pengikut) sekaligus menjadi influencer (berpengaruh). Silih berganti peran semacam itu menciptakan kehidupan komunitas digital amat dinamis karena mereka senantiasa dituntut terus-menerus melakukan adaptasi dan negosiasi terhadap norma, nilai, dan pengetahuan baru (Boyd, 2007: 136).

Relasi-relasi sosial dalam komunitas digital yang melembagakan kontak langsung, komunikasi yang melibatkan banyak orang, keterbukaan pandangan (ide), serta kebebasan interaksi memproduksi informasi yang membentuk kultur unik, oleh Castel disebut culture of real-virtuality (Castel, 2001: 169–170). Di satu sisi, kultur tersebut berkarakter virtual (maya) karena nilai, norma, dan pengetahuan yang tumbuh di dalamnya dimanifestasikan melalui pesan-pesan audiovisual. Akan tetapi, di sisi lain, kultur tersebut juga berkarakter real (nyata) karena nilai, norma, dan pengetahuan tersebut dituangkan secara nyata dalam bentuk gambar, profil, suara, kata, dan sub-text. Informasi tersebut juga beredar luas dan kompleks, tidak hanya berbentuk deskripsi suatu kejadian yang dialami masyarakat nyata, tetapi juga berupa refleksi hasil-hasil diskusi, dialog, atau catatan kritis, bahkan refleksi protes keras yang berujung pada transaksi atau ketegangan politik.

Pertanyaannya yang menarik diajukan adalah sejauh mana sebenarnya relasi-relasi sosial dalam komunitas digital tersebut memiliki dampak signifikan terhadap inklusi sosial atau proses meningkatnya kapasitas akses komunitas terhadap sumber daya (resources), partisipasi mereka dalam formulasi dan eksekusi keputusan publik, serta kerja sama di antara mereka dalam memanfaatkan dan menciptakan peluang. Pertanyaan semacam ini relevan diajukan karena kontak langsung, komunikasi yang melibatkan banyak orang, keterbukaan pandangan (ide), dan kebebasan interaksi yang melembaga dalam komunitas digital dipercaya mampu meningkatkan akumulasi pengetahuan yang dapat dipergunakan untuk meningkatkan inklusi sosial. Jawaban atas pertanyaan tersebut terbelah ke dalam dua pandangan. Pandangan pertama percaya bahwa relasi-relasi sosial semacam itu memiliki efek yang signifikan terhadap inklusi sosial (optimistic in mind). Sebaliknya, pandangan kedua justru meragukannya (skeptic in mind). Perbedaan pandangan semacam itu sampai saat masih menjadi perdebatan (disputes) dalam berbagai diskusi dalam literatur sosiologi dan studi komunikasi. Uraian berikut bermaksud mengupas argumentasi di balik perbedaan pandangan yang bertolak belakang tersebut.

Pandangan optimistic

Seperti dinyatakan pada uraian terdahulu bahwa relasi-relasi sosial dalam komunitas digital melembagakan kontak langsung, komunikasi antar banyak orang, keterbukaan pandangan (ide), dan kebebasan berinteraksi sosial yang mampu menembus batas wilayah geografis, kelas, etnis, agama, gender, dan ideologi. Relasi-relasi sosial semacam itu memproduksi informasi yang tidak hanya bergulir dengan cepat dan menjangkau kalangan yang amat luas, tetapi juga dapat menciptakan stimulan dan mengundang tanggapan langsung (direct response) secara terbuka. Stimulan dan tanggapan tersebut beragam, bisa bersifat positif atau berupa dukungan (support) atau apresiasi, tetapi bisa juga bersifat negatif atau berupa catatan kritis dan protes yang dipicu oleh perlakukan yang diskriminatif. Stimulan dan respons tersebut bisa berkembang menjadi gerakan politik terutama ketika informasi yang bergulir ditengarai menciptakan kelompok tertentu menjadi marginal.

Bukankah catatan kritis dan protes secara langsung dan terbuka semacam itu lazim ditemukan pula dalam kehidupan komunitas nyata? Lalu, apa bedanya? Boleh jadi begitu. Namun, catatan kritis dan protes dalam komunitas digital dapat disampaikan secara langsung karena tidak membutuhkan perwakilan, artinya dapat menembus hambatan terjadinya mediasi yang dikendalikan oleh konspirasi politik. Di samping itu, dalam konteks demokrasi, penyampaian secara langsung dan menembus institusi mediasi juga diyakini mampu mempercepat proses pembentukan aspirasi dan opini sehingga berbagai bentuk kebijakan yang dirancang dan diimplementasikan menjadi lebih memperhatikan harapan publik. Dalam sistem demokrasi, pembentukan aspirasi dan opini juga dibutuhkan untuk menjaga kedaulatan (Dorota, 2006: 43–64).

Lazim pula dinyatakan bahwa relasi-relasi sosial dalam kehidupan komunitas digital memproduksi informasi yang mampu meningkatkan interactivity, yaitu proses berkembangnya tukar-menukar pengetahuan (Bucy and Tao, 2007; Tewksbury and Rittenber, 2012: 94–95). Pengetahuan tersebut bisa berupa kondisi aktual yang sedang menjadi keresahan masyarakat, tetapi bisa pula deskripsi tentang misi yang perlu diketahui publik, bahkan bisa pula terkait dengan efisiensi dan efektivitas kebijakan publik yang telah diimplementasikan. Oleh sebab itu, interactivity dapat berperan sebagai mimbar yang memberi fasilitas bertemunya berbagai macam kepentingan, serta menjadi tempat berdiskusi untuk menemukan alternatif solusi memecahkan masalah-masalah krusial. Peran interactivity semacam itu amat penting bagi berkembangnya inklusi sosial karena di samping melibatkan interaksi banyak kalangan, juga memiliki tautan dengan kepentingan publik.