The Discrimination Towards Indigenous Women in Cultural Practices by Medyline Agnes Elias

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) adopted in 1948 by the international community,proved that human rights were being accepted as universal norms that needed to be respected, protected, and promoted. The phrase in the UDHR “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” means that everyone is equal in claiming their rights without distinction. This is supported by the first paragraph of the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Actions preambular, where it recognizes human rights as a universal norm by stating that “All human rights are universal, indivisible and interdependent and interrelated.” UDHR as a foundation of international treaties later became the foundation of other international human rights instruments including Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). The existence of CEDAW in international law marks the importance of protection and promotion of women’s rights and gender equality between men and women, but in the process of gender equality to some women it is more challenging especially to women from minority communities, like indigenous women. Report from the United Nation (UN) special rapporteur on violence against women by Reem Alsalem stated that indigenous women and girls experienced systematic discrimination in indigenous and non-indigenous justice system (United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 2022). Furthermore, the Human Rights Committee in their General Comment No. 28, art. 3 highlight that the inequality of the enjoyment of rights by women is deeply embedded in tradition, history and culture including religious attitudes.

UDHR ensures that everyone including indigenous women deserve equal rights, art. 1 and 7 of UDHR contain the principle of equality and non-discrimination, and in art. 2 of UDHR prohibits any kind of distinction on the fulfillment of human rights on the basis of sex. Prohibition of discrimination on the basis of sex can also be found in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) art.2 and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) art. 3. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women art. 3 stated that “Women are entitled to equal enjoyment and protection of all human rights and fundamental freedom in the political, economic, social, culture, civil or any other field..”, the enjoyment and protection of rights mentioned in art.3 including the right to equality, the right to be free from all forms of discrimination.

Culture has two sides in human rights aspects, it can be the reason for human rights violation, but it can also protect human rights. A report of a special rapporteur, Farida Saheed on enjoyment of cultural rights of women on an equal basis with men in 2012 stated that there are many practices and norms in society that discriminate against women and it is justified by culture, religion and tradition. Leading experts also stated that social groups mostly suffered human rights violations in the name of culture (Celorio, 2022, pp. 320-231). 75 years since the universal norms of human rights were established and 42 years since CEDAW was instituted, these norms and rights are still not applicable to some indigenous communities because of their cultural beliefs. The reality of equality of human rights to women and men are different in the context of indigenous people. The importance of culture is often mentioned in the establishment of international law, but there is still a gray area of cultural practice and women’s rights.

In Maluku there are the Nualu indigenous people, who are one of many examples of indigenous people in Indonesia. Nualu is an indigenous community located in Seram Island, Maluku. Women’s position in Nuaulu’s social system is considered lower than men, this is because in Nualu, women are considered dirty due to experiencing menstruation. Posune is a local culture from generation to generation in Nuaulu where women who are menstruating or about to give birth are sequestered in a house called Posune. Posune is located on the side or back of the main house. Posune is a forbidden area for men, if a man approaches or enters the Posune even though it is empty it is considered a sin and will be subject to sanctions in the form of being ostracized from the community and in the form of fines set by the customary head. Posune applies to unmarried women and married women. A married woman in the Nuaulu community when she is menstruating she is not allowed to have physical contact with her husband, on the other hand the woman is allowed to cook for her husband, but is not allowed to deliver it directly to her husband. Women in the social system of the Nuaulu community cannot become leaders even if they have menopause, women can only help but are not allowed to sit in positions. The Nuaulu customary system has been passed down from generation to generation, stipulating that women should not become leaders of men (Nina, 2012).

The culture and traditions of Nualu indigenous communities according to international human rights norms violates the rights of women and violates the principle of non-discrimination and universal human rights law. UDHR recognizes that everyone deserves equal rights, but the international community also recognizes indigenous people and their collective rights. The establishment of Indigenous and Tribal People Convention 1989 marked the recognition of indigenous people and tribunal people by the international community. These international instruments created antinomy on the fulfillment of women’s rights and gender equality because on the otherside international community recognize the universal human rights norms, but also recognize indigenous people traditions and culture. This antinomy departs from two perspectives in human rights law theories, namely universalism and cultural relativism. These two theories contradict each other so that there is debate among scholars about these two theories.

The theory of universalism asserts that every human being has certain human rights because they were born as a human being and it made them inherit human rights. Universalism theory believes that human rights are something that cannot be taken away and are intended to protect human dignity. Universalism theory views that human rights are universal and so must be owned by everyone on the basis of equality is not a controversial matter. The theory of universalism can be found in UDHR (Donders, 2010, pp. 16). Unlike the view of universalism theory, the theory of cultural relativism sees that there is cultural diversity that exists everywhere in the world, including views about right and wrong. This view makes cultural relativism theory assume that universal human rights do not exist and the existence of cultural diversity means that an understanding of human rights can be interpreted differently (Donders, 2010, pp. 16).

The debate between scholars about universalism and cultural relativism has divided the scholars into those who support universalism and those who deny universalism. The debate of these two theories started in the second UN World Conference on Human Rights in 1993. The debate has been going around on universal human rights norms as a western values that have been forced to non-western countries (Cerna, 1994, pp. 740). The debate of universalism and cultural relativism also depart from women’s rights (Higgins, 2017, pp. 97). Those who support cultural relativism argue that feminism is a product of western ideology and global feminism is a form of western imperialism. Cultural relativists argue that the conception of human rights by the universalist ignores the collective rights of indigenous and tribal people (Charters C, 2016, pp. 12). In Asia, the universality of human rights concepts face challenges because of private rights. These private rights related to religion, culture, the status of women, the right to marry and to divorce and to remarry, the protection of children, family planning (Cerna, 1994, pp. 744, 746). The conflict between universal human rights principles and cultural relativism often happen in Africa, Asian, and Islamic values. To address this differential issue scholars like Renteln, Donders, and Donelly proposed a way to reconcile the differences between universalism and cultural relativism which are flexibility in interpretation and implementation of rights, cross-cultural dialogue, and focusing on the process and the actors involved (Vleugel, 2020, pp. 41).

To strengthen the scholars’ opinion on how to address the difference of those two theories, we have to consider the role states play in these issues. CEDAW contains the national effort the state should take to maintain gender equality. Art 2(f) of CEDAW mentions for states “to take all appropriate measures, including legislation, to modify or abolish existing laws, regulations, customs and practices which constitute discrimination against women ” and art. 5(a) of CEDAW requires states to modify the social and cultural patterns that discriminate against women. Human Rights Committee (HRC) on general comment No. 28 stated that state have the obligation to ensure human rights enjoyment of all individuals and to ensure that states should to all the necessary steps these steps include “…removal of obstacles to the equal enjoyment of such rights, the education of the population and of State officials in human rights, and the adjustment of domestic legislation so as to give effect to the undertakings set forth in the Covenant. The State party must not only adopt measures of protection, but also positive measures in all areas so as to achieve the effective and equal empowerment of women. “. In art. 3 of ICESCR also highlighted states obligation to ensure the equal rights of men and women. In general comment No. 28 paragraph 32 it might or might not giving us an answer to the debate between universalism and cultural relativism in the aspect of culture and indigenous women’s rights by stating that “The rights which persons belonging to minorities enjoy under article 27 of the Covenant in respect of their language, culture and religion do not authorize any State, group or person to violate the right to the equal enjoyment by women of any Covenant rights, including the right to equal protection of the law. “.

In conclusion, states have the obligation to respect indigenous people culture, tradition, and their collective rights, but also states have the obligation to make an effort to protect indigenous women’s human rights from any violation and discrimination including from the practice of traditions and culture. States playing important rules in the nexus of women’s rights and culture. Universalism is important in protecting individual rights, and cultural relativism is important in protecting collective rights. Human rights practice shouldn’t overlook the fulfillment of individual and collective rights. States should take appropriate action in fulfillment of individual rights of indigenous women’s rights while respecting the collective rights of indigenous people. The protection of all individuals, including indigenous women’s human rights, depends on the state’s political will. The international human rights instruments will not be effective if there is no political will from states.

REFERENCES

Book

Celorio, R. (2022). Women and International Human Rights in Modern Times: A Contemporary Casebook. Women and International Human Rights in Modern Times: A Contemporary Casebook (pp. 1–354). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800889392.

Nina, Johan. (2012). Perempuan Nuaulu: Tradisionalisme dan Kultur Patriarki. Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia.

Vleugel, V. (2020). Human Rights and Cultural Diversity. Between and Beyond Universalism and Cultural Relativism. In Culture in the State Reporting Procedure of the UN Human Rights Treaty Bodies: How the HRC, the CESCR and the CEDAWCee use human rights as a sword to protect

Journal

Cerna, C. M. (1994). Universality of human rights and cultural diversity: implementation of human rights in different socio-cultural contexts. Human Rights Quarterly, 16(4), 740–752. https://doi.org/10.2307/762567.

Charters, C. (2016). Universalism and Cultural Relativism in the Context of Indigenous Women’s Rights. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2887711.

Donders, Y. (2010). Do cultural diversity and human rights make a good match? International Social Science Journal, 61(199), 15–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2451.2010.01746.x.

Higgins, T. E. (2017). Anti-essentialism, relativism, and human rights. In Challenges in International Human Rights Law (Vol. 3, pp. 53–88). Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315095905.

Internet

United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. (2022) , End Violence Against Indigenous Women and Girls: UN Expert. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/06/end-violence-against-indigenous-women-and-girls-un-expert. Accessed March 28th 2023.

Legal Instruments

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)

Vienna Declaration and Programme of Actions

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

Human Rights Committee General Comment No. 28

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women

Author:

Medyline Agnes Elias (Intern at CESASS UGM)

The Development of Jokowi’s plan; why the Omnibus Law is good for the economy but a threat to civil rights in Indonesia

Jokowi’s first development plan: infrastructure

Joko Widodo, better known as Jokowi, is in his second period of the presidency in Indonesia, which had, during his first period, he concentrated policy on the development of the Indonesian economy, especially through investment in the development of the development infrastructure (Hill and Negara 2019). Jokowi knows that infrastructure has been the “Achilles Heel” for developing countries like Indonesia, yet he focused on investment, health systems, and education during his second term. The last law on labour, the Omnibus law, was confirmed by the Jokowi administration last October during the COVID-19 pandemic. The new law will administer labour, environmental and investment regulation (Arifin 2021, Mahy 2021)

Nevertheless, what will be the cost-benefit of this decision? Time will tell whether the Omnibus law will have a good effect or a dangerous effect. However, the people did not see any good in this new government choice, as evidenced by responses from the labour and student movements and academics. A strong infrastructure is essential for the effective functioning of the economy, particularly for reducing economic gaps in the region and reducing the poverty rate. (Firework World Economic Forum 2014).

Comparing the last year of the Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono presidency with the start of the Jokowi period, the stark difference in approaches to economic development is clear. The first act that Jokowi did was to end the fuel subsidy, a subsidy that cost the Government 17.8 billion $ in 2014 and 4.8 billion $ in 2015, enough to divert to a start in promoting the infrastructure, improving the health system, and education ( Negara 2016). Indeed it was already clear that Jokowi planned to dedicate priority to infrastructure investment in the draft of the Medium Term National Development Plan or in Indonesian language RPJMN 2014-2019, where the Government hoped to increase 7 % GPD starting in 2016 (RPJMN report 2014). However, the anticipated GDP target was not reached. Instead, the GDP of Indonesia has grown just 4 /5 % YoY during the slowdown of the global economy created by the COVID-19 pandemic.

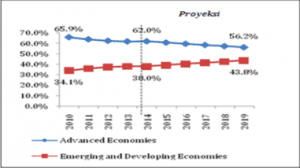

Nonetheless, Jokowi wanted Indonesia to be more economically independent, also not wanting Indonesia to fall behind other countries in Asia like India, China, and Vietnam where infrastructure was developing apace. During his first semester, according to BAPESSAN analysis, no longer Europe and America, but Asia and the Pacific would be the centre of the world economy (Graphic 1).

Graphic 1 demonstrated the prediction made by BAPESSAN.

Source : Bappenas, Oxford Economic Model

Furthermore, Jokowi had understood that the national balance was insufficient without investment from foreign sources, based on investment in infrastructure. Jokowu also knew that, compared with other developing countries like Vietnam or China, Indonesia has a slow and complex bureaucratic system, especially for the legacy of foreign investment. These factors have combined to push the Government to create the controversial new Omnibus Law, cutting many bureaucratic knots in investment to the environment and labour laws.

In this scenario, Jokowi has understood that without foreign Investment, Indonesia cannot develop faster. After the end of Yudhoyono’s period and the start of Jokowi’s period, the budget that Indonesia needed for investment in infrastructure was 300 billion US$, yet the national public finance of Indonesia afforded just 20% of that amount (Deny Sidharta and Jared Heath 2014). According to Hall Hill and Negara (2019), one of the challenges in meeting Indonesia’s massive investment in infrastructure ambition is the weak tax system causing the government shortfalls in the public reserve. Therefore there were a few associated challenges that the Jokowi administration needed to resolve. The first was financing, and the others were land clarity, planning and projecting (Utomo 2017). In addition, Jokowi also faced another huge problem from entrenched local corruption festering through years of power decentralism after the end of the Suharto regime ( Nugroho 2020). In combination, tax inflation, excessive bureaucracy, and massive corruption have pressured Jokowi to accelerate the Omnibus Law to fix his plan to develop the nation’s economy.

The Omnibus Law: worker, gender, environment rights

During the emergence of COVID-19 in Indonesia, the Jokowi Government and The House of Representatives accelerated the procedure for acceptance of the new Omnibus Law on labour in Indonesia to repair the bureaucracy that has, according to the President of Indonesia Joko Widodo (2020), slowed down investment in the country. The problems that made Jokowi create the Omnibus Law were hyper-regulation and bureaucratic knots (Anggraeni, Rachman 2020). According to the Regulatory Quality Index ranking, Indonesia is on the lowest level. Another problem is the decentralisation of power that has increased corruption at the local level (Johannes Nugroho 2020) and slowed down investment procedures. However, the effects on workers, gender, indigenous affairs and the environment are worrying.

Many scholars and NGOs have demonstrated their disappointment to the Government. The Omnibus Law is associated with profound adjustment to legislation that otherwise presents obstacles to investment, including the revision of 79 laws, reorganisation of legislation into 11 clusters and adjustments to more than 1000 articles, including those impacting labour law, social law, and national social security agency law (Amnesty International 2020). Many protections from the 2003 labour legislation have been deleted or modified. A new law on wages and job security is considered a threat, specifically because it does not consider inflation rates for the minimum wage. Therefore is revokes the set city district minimum wage. In practice, without inflation and cost living criteria for determining the minimum wage, poor areas like Papua are further weakened with not enough income to cover the daily cost of living (Usman Hamid 2020).

Another issue of concern is the relative security of the worker when signing a job contract. Under the Omnibus Law, employers cannot offer a permanent job contract but can provide a temporary contract for an indefinite period, meaning that the worker can more easily lose their job. The review of Labour Law presents a new threat with the possibility of performing “work for free”, meaning extra work that does not produce income for the worker. Moreover, article 93 (2) of the Labour Law does not allow for paid time off during menstruation, which is a significant violation of women’s rights.

Additionally, there is concern from environmental NGOs that the new law will increase deforestation in Indonesia (Madani 2020). There is a possibility that by 2056, 5 areas of Indonesia, Riau, Jambi, Sumatra, Bangka Belitung and Center Jawa, will lose their natural forest. Article 29,30,31 of the new law retains the AMDAL (environmental impact assessment requirements) but deletes the function of an independent committee composed of NGOs and activists for the environment. The new law further supports deforestation to increase the palm oil plantation, a dangerous threat that the Government has endorsed with the amplification of the work. It will probably negatively affect the local people who live in the areas that will be deforested, particularly art. 50 (2) sentences 12A and 17B prohibit farming in forestry areas and commercial activities in unregistered forests (Hamid and Hermawan 2020). How to report the NGO Human Rights Wacht (HRW), this is a violation of international norms, such as those expressed in the ICESCR and the UN declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples (HRW 2020 )

On the one hand, the Omnibus Law was created by the Jokowi administration to push ahead with infrastructure and economic development through investment. The new Labour Law attempts to remove excessive bureaucratic administration and red tape relating to foreign investment regulation, liberalizing all foreign investor businesses in any sector, except for currently heavily regulated, banned or illegal industries such as weapons or illicit drugs (Shen and Siagian 2020). The Labour Law also brings tax reforms, an extremely complex issue because tax evasion is one of the highest in the region. The Omnibus Law aims to reduce the tax to 20% for private companies and 17% for Indonesia-listed companies, while foreign workers will be exempt from paying personal income tax on income derived outside Indonesia (Shen and Siagian 2020). On the other hand, the Omnibus Law potentially damages workers’ rights, especially women and indigenous workers, so while investment may grow, the price will be paid by erosion in democracy and civil rights.

Refrences

Anggraeni,R, Rachman, C.I . (2020). Omnibus Law in Indonesia: Is That the Right Strategy?, Atlantis Press, Advances In Economic, Business and Management Research, volume 140 https://doi.org/10.2991/aebmr.k.200513.038

Amnesty International. (2020) Commentary on the labor cluster of the Omnibus Bill on Job Creation ( RUU CIPTA KERJA) Jakarta, Index: ASA 21/2879/2020

Amnesty International. (2020) Omnibus Bill on Job Creation Poses “Serious Threat” to Human Rights,

Amnesty International. (2020) Submission to United Nations committee on the elimination of discrimination against woman

Arafin, S. (2021), Illiberal Tencencies in Indonesia Legislation:te case of the omnibus law on job creation. The Theory and Practive of legaslation Juornal, Vol 9 N.o 2 https://doi.org/10.1080/20508840.2021.1942374

Bland B. (2020), Man of Contradictions, Joko Widodo and the struggle to remake Indonesia, Lowy Institute, Penguin Random House Australia

BAPPENAS, Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah 2014-2019

Breuer L.E, Guajardo J, Kinda T. (2018) Realizing Indonesia’s Economic Potential, International Monetary Fund (IMF)

Emont J. (2016) Visionary or Cautious Reformer? Indonesia President Joko Widodo’s Two Years in Office https://time.com/4416354/indonesia-joko-jokowi-widodo-terrorism-lgbt-economy/

Firduas F. (2020) Indonesia Fear Democracy is the Next Pandemic Victim, Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/04/indonesia-coronavirus-pandemic-democracy-omnibus-law/

Hamid. U., Ary (2020). Hermawan, Indonesia’s Omnibus Law is a bust for human rights, New Mandala. https://www.newmandala.org/indonesias-omnibus-law-is-a-bust-for-human-rights/

Hill H, Negara S.D. (2019) ; The Indonesia Economy in Transition, Policy challenge is Jokowi era and beyond, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute

Human Rights Watch. (2020) Indonesia; New Law Hurts Workers, Indigenous Groups, Massive Omnibus Bill Passed Little Public Consultation. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/15/indonesia-new-law-hurts-workers-indigenous-groups

HRW Ihanuddin, Krisiandi. (2020) Jokowi Ungkap Alasan RUU Cipta Kerja Dikebut di Tengah Pandemi, Kompas.com

Negara D. (2016 ) Indonesia’s Infrastructure Development Under The Jokowi Administration, Southeast Asian Affairs, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute

Nugroho J. (2020) Indonesia’s Omnibus Law won’t kill corruption , The Lowy Institute. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/indonesia-s-omnibus-law-won-t-kill-corruption

Madani (2020) . Tinjuan Risiko RUU CIPTA kerja terhadap hutan alam dan pencepain komitmen iklim Indonesia. https://madaniberkelanjutan.id/2020/05/06/tinjauan-risiko-ruu-cipta-kerja-terhadap-hutan-alam-dan-pencapaian-komitmen-iklim-indonesia

Mahy,P. (2021) Indonesia ‘s Omnibs Law on Job Creation: Reducing labour Protections in a Time of Covid-19, Monash Business School, Monash University, Labour, Equality and Human Rights Research Gruop Working Paper N.o 23

Mighty Earth. (2020) Indonesia’s Omnibus Bill Approval Poses Dire Threat to Anti-Deforestation Efforts. https://www.mightyearth.org/2020/10/05/indonesias-omnibus-bill-approval-poses-dire-threat-to-anti-deforestation-efforts/

Shen,J.,Siagian,C. (2020). Indonesia‘s Omnibus Law: A magic wand amidst a global pandemic? https://singaporeglobalnetwork.gov.sg/stories/business/indonesias-omnibus-law-a-magic-wand-amidst-a-global-pandemic/

Sidharta D, Jared Heath. (2014) Building Effective Partnerships, Jakarta Post

World Economy Forum (2014) The Global Competence Index 2014-2015 www.weforum.org/gcr.

Utomo, Wahyu. (2017). Tentang Pembangunan Infrastruktur di Indonesia. kppip.go.id.

About the Author:

Aniello Iannone is a candidate for Master of Political Science, Diponegoro University, and Junior analyst at the Institute of Analysis and International Relations (IARI).

Indonesia Risks Factors in Terrorism

In Indonesia, terrorism is a threat that affects the nation’s social/political order and bring light to tensions existing in the country. Indonesia has the largest Muslim majority globally; however, Indonesia is a secular country adopting a liberal reform of Islam and accepting religious tolerance towards other minorities. However, terrorist groups have voiced their radical opinions on Indonesia’s secularism calling for the country to be an Islamic state and achieve these goals through violence. The Indonesian government has taken counter-measure to tackle these terrorist threats, but these measures are criticized by Human Rights Organisations (HRO). Because Indonesia has created many anti-terror repressive laws, violating the freedom of speech and the task force Densus 88 has broken many Human Rights Violations (HRV). This brings into question is terrorism the overall threat towards Indonesia, I would argue no but state that terrorism must be a risk that does possess a threat, however, cannot endanger Indonesia’s democratic institution. I would argue that Indonesia’s anti-terror laws are a danger to Indonesia’s democracy and Indonesia’s Counter-Terrorism (CT) agencies violate human rights laws (HRL). These are the overall threats that endanger Indonesia’s democracy and why treating terrorism as a risk can be approached with de-radicalization programs. I will explain how Indonesia can treat terrorism as a risk and not an existential threat like climate change and can be mitigated with soft-approach policies, and I will outline the dangers of the hard-approach undertaken by the Indonesian government.

Climate change, ethnic tensions, and inequality are challenging problems that Indonesia faces as a nation. Climate change has undoubtedly forced the Indonesian government to adopt new environmental laws but is yet to be taken seriously by the government (Kheng and Bhullar, 2011). The lack of governance to combat these growing inequalities and the existential threat of climate change has been met with criticism because the Indonesian government has failed to approach this with innovative policies. Instead, the government has taken a harder stance to combat terrorism, creating or reforming new laws enacted recently by the Indonesian parliament. The new laws have alarmed HRO and scholars criticizing the government for violating the freedom of speech and pushing the government into post-authoritarianism (Kusman and Istiqomah, 2021). Critics have argued that there can be other policies that Indonesia can adopt such as the de-radicalization program which requires serious reform because the threat of terrorism is continuing to evolve (Gindarsah and Priamarizki, 2021). Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) and other terrorist organizations are continuous threats, and the rise of lone-wolf terrorism will challenge Indonesia’s counter-terrorism agencies. The risk factors of terrorism in Indonesia are a present danger, but CT actions against terrorists are needed for a soft approach or hard approach to combat the risks involving the rising threat of terrorism in the country.

The war on terror is the defining factor that has pushed the Indonesian government to enact new repressive policies. Since the 2002 Bali bombing, the Indonesian parliament has rushed anti-terror laws to combat terrorism, but these laws have constrained individual rights in the country (Nakissa 2020). One of these laws, called “the Revisi Undang-Undang Anti-terrorism” allows the military to fight against terrorism (Haripin, Anindya, Priamarizki, 2020). The allowance of having the Indonesian military against the fight against terrorism is seen as an abuse of power because it pushes the nations back into the former post-authoritarian roots (Kusman and Istiqomah, 2021). The growing level of military force does have a negative consequence, for example, the United States (US) military war on terror is met with many criticisms among societies (Satana and Demirel-Pegg, 2020). Allowing the military to fight terrorists will create tension among the civilian population and could involve higher civilian casualties deaths if the military is called to eliminate terrorists in the region. One example was when the military was deployed to crush the terrorist organization called East Indonesia Mujahideen in the region called Poso, in central Sulawesi Indonesia (Nasrum, 2016). The military presence only created tension and fear amongst the civilian population because they were afraid and would be caught against the terrorist and military cross-fires (Nasrum, 2016). Allowing the military provides a challenge to Indonesia’s democratic institutions, which has weakened under President Widodo’s reign. President Widodo has taken great lengths to weaken the HRO and anti-corruption agencies in Indonesia (Kusman and Istiqomah 2021). The latest push by President Widodo to enact new counter-terrorism new laws is threatening Indonesia’s democracy because will these hard approaches to combat terrorism as risk be effective.

Indonesia’s hard-line approaches against terrorism are dangerous, especially allowing the military to fight terrorist groups, thus creating tension amongst the civilian population. Indonesia’s own CT task force called Detachment 88 or Densus 88 is being met with criticism and accusation from HRO (Arrobi 2018). Densus 88 task force was established in 2003 after the 2002 Bali bombing assisted by the United States and the Australian government and has successfully disrupted terrorist operations (Carnegie 2015 and Barton 2018). Densus 88 is one of the world’s best task force because Densus 88 has successfully prevented many terrorist threats in the country. Since 2002 Densus 88 has arrested 800 jihadists and thwarted 15 attacks in 2017, proving how robust and effective the task force has become (Arrobi 2018). Despite these successes, Densus 88 has violated human-rights laws by torturing suspected individuals, extra-judicial killings, tampering with evidence, and interfering with defence lawyers for easier convictions (Nakissa 2020). Indonesia’s own National HRO Komisi Nasional Hak Asasi Manusia (Komnas HAM) has admitted to Densus 88 “excessive use of force” (Nakissa 2020). Torture tactics conducted by Densus 88 is bound to have negative consequences because many reports and evidence shows that torture is the worst interrogation method conducted (Rejali 2007). Individuals are more likely to lie to get out of torture and only radicalize their supporters to commit attacks against the state (Rejali 2007). Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict THE RE-EMERGENCE OF JEMAAH ISLAMIYAH (2017) reports explained the death of a terrorist suspect Siyono who died in police custody. Siyono’s death from the announcement was met with outrage amongst the civilian population and called for greater accountability for Densus 88. The hard-approach measures taken to combat terrorism in Indonesia has only provided more threats in the country because the violation of HR has only angered the civilian population. It is why a much broader scope of Indonesia’s de-radicalization program can mitigate the risk associated with terrorism.

A soft-approach towards terrorism is needed with Indonesia’s de-radicalization program, which requires policies and reform (Gindarsah and Priamarizki 2021). In Indonesia, terrorism is evolving, and terrorist organizations are starting to use social media to bolster their support and increase their recruitments ( Habulan et al. 2018). Jamaah Ansharud Daulah (JAD) the organization involved with 12 terrorist attacks, including police officers’ targeting, is starting to use social media as a propaganda tool (Habulan et al. 2018). Indonesia’s national counter-terrorism agency (BNPT) will need to counter these messages with good prison sentences and education reform to counter-terrorism. De-radicalization programs have been shown to work in Indonesia, individuals have realized that the action they have committed is wrong and speak out against inciting violence. The book “why terrorist quit” by Julie Chernov Hwang (2018) had shown interview reports where the individual questioned his action when he bombed the church killing innocent civilians. Evidence shows that even installing Muslim leaders to shut down radical preachers can shut hate messages and change the individual perspective (IPAC 2014). Prison and Education reform is the best soft approach needed to boost Indonesia’s de-radicalization program. Evidence shows that individuals can change their perspective when re-educated and shown Islam’s correct teaching (Hwang 2018).

The risk involving terrorism is continuing to dominate Indonesia’s social and political order, and with the rise of social media, terrorists are starting to change their tactics and adapt their propaganda. Indonesia’s hard-approach towards terrorism will undoubtedly create more risks testing Indonesia’s democracy, which is already under threat. President Widodo pushing the parliament to introduce new CT laws violates the freedom of speech in the country. Repressive anti-terror laws approving the military to engage against terrorist groups will create tension amongst civilians and push Indonesia back towards the nation’s post-authoritarian roots. Densus 88 have already come under scrutiny for breaking human rights laws and has received backlash from the public. Indonesia’s government and the (BNPT) must approach terrorism as a risk factor which can involve soft-approach policies. De-radicalization programs have proven to change former terrorist perspective and can introduce these individuals back into society. Terrorism treated as a risk can move toward reform of education and good prison sentences instead of the Indonesian government’s draconian policies. Terrorism if treated as a risk factor proves that the threats are there, but Indonesia’s policies do not have to be affected by terrorism, but a more civilian, human right, and justice approach can combat the threat of terrorism in Indonesia.

About the author:

Dave Pereira was a participant of Development Studies Professional Practicum (DSPP) Virtual Internship at ACICIS Indonesia. As part of this program, he also conducted an online internship in PSSAT (Pusat Studi Sosial Asia Tenggara or CESASS (Center for Southeast Asian Social Studies) UGM on January 8th – February 12th, 2021.

Radical Islam, The Relationship between Politics, Security and Terrorism in Indonesia

Terrorism is often an act of violence, or threat to act, that is politically or religiously charged. A true worldwide definition of terrorism does not currently exist, yet there are specific characteristics that we can link to the concept. One of the struggles of understanding terrorism in academic debates stems from the lack of a solid definition. It has been argued by many scholars that such a definition cannot ever exist (Jackson et al. 2011). Difficulties scholars have agreeing on a definition of terrorism come from it being contextually determined, and definitions in this area can often include political bias. Over-generalized definitions are mostly what we have been left with around the world. Indonesia’s Anti-terrorism Law (ATL) of 2002, gives a description of terrorism. This law does not define terrorism in any strict sense but instead claims that the crime of terrorism can be any act that fulfils elements of the crime under this law. There are critical terms left undefined and therefore subjective to various interpretations, such as ‘widespread atmosphere of terror or fear’. Widespread is not defined to a radius, neither is fear define to a degree. The vague terms included in this description has been criticized for being applicable to various cases that may not involve terrorism (Butt, 2008). A lecturer at Murdoch University, Dr Ian Wilson (2020), argues that there are no terrorist organizations, there are only political groups that use terrorism as a tactic. This is important to understanding the link between terrorism and politics in Indonesia. The motives of these groups are politically charged and stem from a discomfort with Indonesian democracy.

There was much debate about the security of Indonesia being threatened with the release of Abu Baker Ba’asyir early this year. Jones (2019) argues that his release is unlikely to suddenly increase the risk of terrorism in Indonesia. However, he is still very much able to preach radical ideas and is under no restrictions from doing so. In 2014, while in prison, Ba’asyir pleaded his allegiance to the Islamic State and its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. According to Jones (2019), President Joko Widodo’s decision to release him violated standard regulation when Ba’asyir did not need to sign a loyalty pledge to the government. ‘It would seem to violate Regulation 99 of 2012 from the Ministry of Law and Human Rights, which makes the early release for certain categories of offenders, including convicted terrorists, contingent on their willingness to sign a written loyalty oath to the Indonesian government’ (Yulisman, 2019). Abu Baker Ba’asyir was exempt from signing. This shows a political weakness in the fight against terrorism. While the security of Indonesia is seemingly not threatened by his release, the political leaders have undermined the regulations that actively contribute to counterterrorism measures through de-radicalization.

Radical political groups and terrorism acts undermine the political sphere and create security issues in Indonesia. The continued pressure from political Islam has been a developing issue in Indonesia for many years. Radical Islamist groups continue to create fear through terror tactics around Indonesia and political Islam threatens Indonesia’s democracy. The Indonesian government has limitations, and they have fallen short when it comes to dealing with terrorism. Indonesia was a presentation of democratic transition for many years, especially for countries like them with large Muslim populations. Liberalism and perhaps even tolerance in Indonesia can be seen to be under threat. Tim Lindsey in his article ‘Retreat from Democracy: The Rise of Islam and the Challenge for Indonesia’ (2018), argues that liberal democracy is in contest with Muslim conservatives. He points out the paradox that the voices of tolerance which sought to present Indonesia as a Muslim Democracy now face opposition from Muslim conservative intolerance empowered by that very democracy.

Within the Muslim community in Indonesia there is a battle between moderates and conservatives over the essence of Islam and its presence in political and social structures, institutions, and culture. As Shira Loewenberg (2018) argues, there are two very different futures for Indonesia that are fought for by the two sides. The moderate side fights for Indonesia’s democracy, and religious freedom, while the conservative side fights for an Islamic state, governed under Islamic law and opposed to democracy. However, most scholars agree that it is unlikely Indonesia will formally be an Islamic state anytime soon.

In Vedi R. Hadiz’s ‘Towards a Sociological Understanding of Islamic Radicalism in Indonesia’ (2008), he discusses radical Islam as being deeply rooted in contemporary world order. Hadiz makes comparisons between the fear of political islam, with the growing discomfort surrounding the state of democracy in Indonesia. In the past, organized Islam has been a major source of opposition to democracy, and appointed leaders. This pressure continues to threaten democracy, while being given a platform to speak by that very democracy. Blasphemy laws in Indonesia are just one example of political Islam being put at an advantage by democracy (Connelly & Busch, 2017). The jailing of Ahok, the Jakarta governor, in 2017, demonstrates the problem. President Joko Widodo and his government struggled to respond effectively. They can be argued to have been intimidated by the attacks on the governor and the calls for ending Jokowi’s presidency as well. The governor lost his election and was jailed under blasphemy laws. Islamic values are imposed on laws and norms gradually, such as increasing limitations on free speech, restrictions on clothing and sexuality, as well as the banning of alcohol. As a model for this approach many look to Malaysia (Lindsey, 2018).

The relationship between politics, security and terrorism in Indonesia is grounded in the largely Muslim population, and is threatened by extremists. Politics, including laws and norms, can be seen to be continually being influenced by conservative Islam. Threats from terrorism are very real, and undermine the security attempts made by the Indonesian government.

References

Butt, S. (2008). Anti-Terrorism Law and Criminal Process in Indonesia. ARC Federation Fellowship ‘Islam And Modernity: Syari’ah, Terrorism and Governance in South-East Asia’. Retrieved from https://law.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/1546327/AntiTerrorismLawandProcessInIndonesia2.pdf

Connelly, A., & Busch, M. (2017). Indonesian democracy: Down, but not out. Retrieved 28 January 2021, from https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/indonesian-democracy-down-not-out

Jackson, Richard, Lee Jarvis, Jeroen Gunning, and Marie Breen Smyth. 2011. “Conceptualizing Terrorism”. In Terrorism: A Critical Introduction, 1st ed., 99-121. Palgrave Macmillan. https://content.talisaspire.com/murdoch/bundles/5bfcf2e6540a2630f54558e4.

Jones, S. (2021). Indonesia: releasing Abu Bakar Ba’asyir wrong on all counts. Retrieved 12 January 2021, from https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/indonesia-releasing-abu-bakar-ba-asyir-wrong-all-counts

Lindsey, T. (2018). Retreat from democracy? The rise of Islam and the challenge for Indonesia. Australian Foreign Affairs, (3), 69-92.

Loewenberg, S. (2018). Threats to Indonesia’s Democracy. Retrieved 21 January 2021, from https://www.ajc.org/news/threats-to-indonesias-democracy

Vedi R. Hadiz (2008) Towards a Sociological Understanding of Islamic Radicalism in Indonesia, Journal of Contemporary Asia, 38:4, 638-647, DOI: 10.1080/00472330802311795

Wilson, Ian. “Introducing the unit & the challenges of conceptualizing terrorism” [lecture]. In Pol 234: Terrorism in a Globalized World, Murdoch University, 27 February 2020.

Yulisman, L. (2019). Indonesia president orders review of planned release of radical cleric Abu Bakar Bashir. Retrieved 13 January 2021, from https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/indonesia-president-orders-review-of-planned-release-of-radical-cleric-abu-bakar-bashir

About the author:

Megan Connelly was a participant of Development Studies Professional Practicum (DSPP) Virtual Internship at ACICIS Indonesia. As part of this program, she also conducted an online internship in PSSAT (Pusat Studi Sosial Asia Tenggara or CESASS (Center for Southeast Asian Social Studies) UGM on January 8th – February 12th, 2021.

Crimes Against Humanity in the Philippines: How does ICC response towards Duterte’s War on Drugs?

Rodrigo Duterte was appointed as President of the Philippines on July 1, 2016. At the same time, he realized his political promise to catch up drug lords, through a war on drugs policy. War on drugs attempts to eliminate drug trafficking and use in the Philippines by arresting and/or killing dealers, both large dealers and small dealers, and drug users. In its implementation, Duterte hired police, paramilitaries, and assassins (BBC News, 2016).

The Philippines did suffer from drug emergencies as Duterte said in his speeches. According to data from the Dangerous Drugs Board (DDB) in 2016, drug users in the Philippines reached 1.8 million, equivalent to 1.8% of the total population of the Philippines which reached 100.98 million people. The data was collected from the age range of 10-69 years which at least had used drugs even once in his life (Gavilan, 2016).

In an interview with Russia Today, Duterte said that drugs were a threat that could destroy the young generation of Filipinos who became assets for the country. He repeatedly said that he would kill anyone who was caught in a drug case (Russia Today, 2017). Duterte gave an order to arrest drug addicts and dealers if possible. However, if they fight with violence that can threaten the lives of the police or security officers who arrest them, the police or security officers are allowed to kill (Al Jazeera English, 2016).

From July 1, 2016, to September 30, 2018, war on drugs has resulted in 4,948 people being killed in the operation. Moreover, data from the Philippines National Police (PNP) showed that 22,983 people were victims of murder since the implementation of the war on drugs. This number does not include thousands of others killed by gunmen (Human Rights Watch, 2018).

Human Rights Constitution in the Philippines

The Philippines has committed to the promotion of human rights, as evidenced by the ratification of several international agreements on human rights, namely the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) on October 23, 1986. Furthermore, the ICCPR was instrumental in determining penalties for lawbreakers in the Philippines.

After ratifying the ICCPR, the Philippines then drafted its constitution by including human rights values in article 3 about Bill of Rights of the Philippine Constitution, which was ratified in 1987. Before that, the Philippines did not have a fixed constitution. Regulations imposed in his country are governed by the president in office at that time. That is what makes human rights regulations unclear in the Philippines before the Philippine constitution is ratified. Until now, the Philippine constitution has become the only law that underlies human rights regulation in the Philippines, excluding international agreements that are a source of international law.

In the same year, 1987, the Philippines became the first Asian country to abolish the death penalty. The Philippines abolished the death penalty twice, first abolished in 1987, and the second in 2006 (Armandhanu, 2016). After 2006, the Philippines did not apply the death penalty. Meanwhile, Duterte said he would re-implement the death penalty and direct shooting at drug dealers.

However, until 2018, the Philippine constitution has not been changed. Even though Duterte continued shooting at drug lords. Constitutionally, that cannot be justified. Plus, the Republic Act No. 9165 regarding drugs also does not write the death penalty, but a life sentence.

Violations against Human Rights in the War on Drugs Policy

The Philippine Constitution which specifically deals with human rights as contained in article 03 of the bill of rights. Article 03 consists of 22 sections that discuss the details of individual and community rights. War on drugs policy violated Article 03 Chapter 01, Chapter 14 (1), Chapter 19 (1), and Chapter 22 in the Philippine Constitution.

- Chapter 01: “No person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, nor shall any person be denied the equal protection of the laws” (The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines, 1987, p. 3). It shows that every human being has the right to live and obtain freedom. Considering that part, President Duterte has violated the life rights of his citizens by killing without a court of law. This shows that the murder of drug dealers that he did was unfair to the community and violated the basic rules of the human rights constitution in the Philippines.

- Chapter 14 (1): “No person shall be held to answer for a criminal offense without due process of law” (The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines, 1987, p. 5). The Chapter clearly emphasizes that no individual can be asked for an answer to a criminal act without legal process. In other words, each individual has the right to undergo legal proceedings for his criminal actions. In the case of President Duterte, the state did not provide an opportunity for drug dealers to undergo regulated legal processes. The drug dealers were shot directly no matter where and whenever, without a court of law. This will be related to chapter 22 concerning the bill of attainder.

- Chapter 19 (1): “Excessive fines shall not be imposed, nor cruel, degrading or inhuman punishment inflicted. Neither shall death penalty be imposed, unless, for compelling reasons involving heinous crimes, the Congress hereafter provides for it. Any death penalty already imposed shall be reduced to reclusion Perpetua” (The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines, 1987, p. 6). The punishment given by the state must be humane by not harassing human dignity. If you have to be given a death sentence, it only applies to very violent crimes. While the war on drugs contradicted the Chapter. According to President Duterte, drug crime is the most heinous crime in the Philippines because it has damaged the young generation of Filipinos (Regencia, 2016). However, many dealers who were killed were small dealers and the days were increasingly out of control. Judging in chapter 14 (1), every violator of the law, whether a minor violation or a serious violation, is obliged to undergo legal proceedings at first. In this case, the Philippines must also provide clear boundaries regarding small-scale drug dealers and drug dealers on a large scale, so that there is a clear and fair law to try the case.

- Chapter 22: “No ex post facto law or bill of attainder shall be enacted” (The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines, 1987, p. 6). Ex post facto law is a law that is implemented after being given a sentence as a result of subsequent actions. Then the bill of attainder is an act that states someone is guilty and sentenced without trial at first. In chapter 22 states that ex post facto law or bill of attainder is not invited, which means that no sentence is given without a court. Reviewing President Duterte’s policies, the policy violates chapter 22 of the Philippine constitution. The killings committed did not take the court first, but immediately killed once the target was weak.

At its conclusion, President Duterte’s policy injured the Philippine constitution itself. Four Chapters of Article 03 have been violated. That was the reason for the Philippine Supreme Court to warner President Duterte to dismiss his policies (Al Jazeera, 2017). However, Duterte insisted on continuing this policy based on the emergency threat (Al Jazeera English, 2016).

Introduction to the International Criminal Court (ICC)

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is an international regime that focuses on handling crimes against humanity. The ICC was established on July 1, 2002, through the Rome Statute agreement, which gave legitimacy to the ICC to try perpetrators of crimes against humanity. Based on the elements of crime contained in the Rome Statute, four major crimes must be dealt with by the ICC, namely genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and crimes of aggression (International Criminal Court, 2011). These issues have similarities with the issue of crime handled by the UN Security Council. For this reason, the two institutions coordinate with each other in dealing with these issues.

The ICC will prosecute genocide perpetrators, crimes against humanity, or war crimes on and after July 1, 2002 – so that any crimes that occur before that time cannot be tried through the ICC. These three crimes can be tried by the ICC if carried out by nationals of ICC member countries, in the territories of ICC member countries, or in countries that accept ICC jurisdiction. Besides, as explained above regarding the coordination of the ICC and UNSC, the UNSC can refer criminal cases to the ICC Prosecutor to be tried under the resolution adopted under Chapter VII of the UN charter.

Meanwhile, for the case of a new crime of aggression, it will be regulated on July 17, 2018, on the recommendation of the UNSC. In this case, the ICC can try parties’ guilty outside of the ICC membership. If the UNSC does not propose an investigation of cases of aggression, then the ICC can conduct investigations independently or based on proposals from member countries. However, before conducting an investigation the ICC needs to check the status of the case at the Security Council, whether the case has been handled or not (International Criminal Court, n.d.).

In conducting the legal process, the ICC has several stages, namely as follows:

- Preliminary examinations

- Investigations

- Pre-Trial stage

- Trial stage

- Appeals stage

- Enforcement of sentence

Because the ICC upholds human rights values, the penalties applied are only imprisonment and fines, as stated in the Rome Statute Chapter 7, Article 77 (International Criminal Court, 2011). The ICC does not implement the death penalty.

ICC Action Plan on the Philippines’ War on Drugs

On February 8, 2018, the ICC announced the opening of preliminary examinations on the war on drugs case launched by the Government of the Philippines since July 1, 2016. The examination focuses on thousands of drug users who have been killed and extrajudicial killings in the context of anti-drug police operations (Gallaghera, Raffleb, & Maulanab, 2019). It should be emphasized that ICC conducted preliminary examinations, not yet at the investigation stage. Preliminary examinations are needed to observe the urgency of the case, jurisdictional power, and justice. If all components have been fulfilled and with careful consideration, this case can be raised towards the investigation phase (International Criminal Court, 2018).

The Philippines responds to the ICC’s actions by writing an official written statement stating that it left the Rome Statute on March 17, 2018. However, legal proceedings against the Philippines are still ongoing. The waiting period from exit statement to the official exit is one year. During this period, the ICC will continue to conduct examinations on the Philippine government for its war on drugs policy that killed many people.

References

The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines.

Al Jazeera. (2017, January 15). Duterte: No One Can Stop Me From Declaring Martial Law. Dipetik April 29, 2019, from Al Jazeera: https://www.aljazeera.com/amp/news/2017/01/duterte-stop-declaring-martial-law-170115034431700.html

Al Jazeera English. (2016, Oktober 15). Rodrigo Duterte on Drugs, Death, and Diplomacy | Talk to Al Jazeera. Dipetik April 25, 2019, from Al Jazeera English: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S2KtLTXXej8

Armandhanu, D. (2016, Mei 16). Rodrigo Duterte Akan Terapkan Lagi Hukuman Mati di Filipina. Dipetik April 24, 2019, from CNN Indonesia: https://www.cnnindonesia.com/internasional/20160516140021-106-131030/rodrigo-duterte-akan-terapkan-lagi-hukuman-mati-di-filipina

BBC News. (2016, Agustus 26). Philippines Drugs War: The Woman Who Kills Dealers for A Living. Dipetik April 29, 2019, from BBC News: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-37172002

Fehl, C. (2004). Explaining the International Criminal Court: A ‘Practice Test’ for Rationalist and Constructivist Approaches. European Consortium for Political Research, Vol. 10(3), 357-394.

Gallaghera, A., Raffleb, E., & Maulanab, Z. (2019). Failing to Fulfil the Responsibility to Protect: the War on Drugs As Crimes Against Humanity in the Philippines. The Pacific Review, 1-31.

Gavilan, J. (2016, September 19). DDB: the Philippines Has 1.8 Million Current Drug Users. Dipetik April 23, 2019, from Rappler: https://www.rappler.com/nation/146654-drug-use-survey-results-dangerous-drugs-board-philippines-2015

Human Rights Watch. (2018). Philippines: Events of 2018. Dipetik April 25, 2019, from Human Rights Watch: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/philippines#1ff4dc

International Criminal Court. (2011). Elements of Crimes. The Hague: International Criminal Court.

International Criminal Court. (2011). Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. The Hague: International Criminal Court.

International Criminal Court. (2018, Maret 20). ICC Statement on The Philippines’ Notice of Withdrawal: State Participation in Rome Statute System Essential to International Rule of Law. Dipetik April 28, 2019, from International Criminal Court: https://www.icc-cpi.int/Pages/item.aspx?name=pr1371

International Criminal Court. (t.thn.). How the Court works. Dipetik April 28, 2019, from International Criminal Court: https://www.icc-cpi.int/about/how-the-court-works/Pages/default.aspx#legalProcess

International Criminal Court. (t.thn.). The Philippines. Dipetik April 28, 2019, from International Criminal Court: https://www.icc-cpi.int/philippines

Regencia, T. (2016, Agustus 10). Duterte Threatens Martial Law If ‘Drug War’ Is Blocked. Dipetik April 29, 2019, from Al Jazeera: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/08/duterte-threatens-martial-law-drug-war-blocked-160805170518830.html

Russia Today. (2017, Mei 22). ‘They want me to fight China. It’s gonna be a massacre!’ – Duterte to RT (FULL INTERVIEW). Dipetik April 25, 2019, from RT: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rHjlCmdyesY

—

This article was written by Laras Ningrum Fatma Siwi, an undergraduate student of International Relations Studies at the Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, while working as an intern at Center for Southeast Asian Social Studies (CESASS).

—

Photo by Aditya Joshi on Unsplash

A Portrait of Southeast Asia’s Illegal Wildlife Trade Reality

Introduction

If there’s one thing that Southeast Asia should be known for, it is one thing; Diversity. This region is the home to many cultures, belief, traditions, cuisines that extends all the way to its rich biodiversity. The region hosted millions of species that ranges from both animals and plants. Many states in this region are in fact, aware of this fact and the notion of this leads majority of states in Southeast Asia to sign and ratify the CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna 1975 ) within their national legislation, as a measure taken to protect 3000 species of flora and fauna. In Indonesia, CITES has already been ratified into Law no 5 Year 1990 for the conservation of living resources and Ecosystems. The ratification process itself are divided into 3 (three) criteria in which the former one (1) are deemed the most effective, while the latter one is the deemed ineffective (3) due to the lack of alignment between the content within the legislation and the aforementioned conventions.

However, based on the research conducted by UNEP, wildlife trade still occurs in many parts of the world. UNEP reported that illegal trade in wildlife is generally around 7-23 billion dollars annually. Furthermore, the reason why the focus shall be in Southeast Asia are because, the growth rate in environmental crime within the region corresponds with the GDP growth rate in many Asian states to the number of 5.1 up to 7.5% . This is an activity that should be prevented and eradicated not only by enacting legislations but also, to understand the reason behind these activities. The reality of the implementations of these policies in Southeast Asia are still ineffective due to the fact that legislations are not enough to tackle a problem that has been deeply rooted within the region.

In fact, the trade of wildlife in East and Southeast Asia has a long history. In parts of the region, kings presented live animals and wildlife to the leaders of the neighboring states as a “diplomatic tool” and during the first 20th century, the trade of wildlife has been a major source of foreign exchange. The description above reflected the mindset of the people within the region that still thinks that wildlife can be utilized to their own benefit. It is not enough to tackle wildlife trading without analyzing the root of the problem, due to the fact that both domestic and international illegal wildlife trade is a complex business that has the stimulant of both socioeconomic and cultural forces.

Commercial Structure & Business Operation

To understand this horrible business activity, one must grasp the notion on the structure of this activity, in which there are three roles that Southeast Asia countries partake. It is divided as a Source, Conduit and Consumer states. The source country is where these biotas are being taken away from their natural habitat to be transferred to the conduit states, where these species are being stored and sold to the collectors that originate from consumer states. This activity are driven by many factors as well; Southeast Asia’s rising living standards , infrastructure development that enhance the mobility of the activity, myths that created demands to consume a certain animal parts to the opening up of a several states economy to an international market – based policies that improve international trade connections.

Due to the illegality factor of this commercial activity, there’s a several “methods” that might be used by the seller such as (1) targeting new source areas or countries for a particular species, (2) new smuggling methods and routes to avoid detection and most generally, (3) to exploit the weak wildlife- related law enforcement. The former one is a method where the traders exploited new areas in order to capture or extract one particular kind of species due to the fact that the previous area does not accommodate the needs of the consumers anymore. The second method involved new and different methods upon transporting wildlife to their conduits. In Vietnam, wild bears are being smuggled using fake army vehicles, ambulance with the biota dressed as the patient. The latter one is the most horrible one, where the smugglers that are caught smuggling illegal biotas, convince the customs official that the species on their possession are actually legal to trade, and this created a much less penalty than the one actually imposes by law. This is a very sad reality; where it shows that there is a very minimum cooperation between the customs official and law enforcers; that shows the lack of understanding of the subject matter of the regulations that has already been created.

Vital Source of Income

One of the reason why enacting the previous rules and regulations are insufficient are due to the fact that these activities are still, the vital income of populations living in some parts of Southeast Asia, especially in the greater sub-mekong area, especially in Vietnam and Laos. In Nakai – Nam theun National Park Laos, 59% of the villages admit that terrestrial wildlife had been an important source in their village over the last decade, and they do admitted that overall species of wildlife number had declined over the last decade. The usual frequently-sold species are the one that suffered from the effect the most, experiencing drops to 75%, and these are due to many illegal activities happening in the forest that makes these species lose their habitat. Notwithstanding of the obstacles, this still create a very narrow part of the populations specializing in becoming hunters specializing in wildlife trade, in which makes it a career decision. These people are equipped with new skills and equipment that might helped them do their jobs, such as tranquilizing drugs and other process that might ease their burden to capture one wildlife species.

Other than the economic factors, there are still many factors that could leads into these activities. However, the brief description above is an accurate portrayal to this illegal activity. In order to deal with this problem effectively creates urgencies for states, to learn more about the mechanism of wildlife trade. Technology can be used as an effective tool to compile data in regards to list of the identification of types of illegal species, demands, routes & to list every trading activities possible. Further analysis in regards to both social and economic factor of this problem is also necessary; in order to understand the demands of this activity.

There also needs to be better cooperation between both the local, regional and national level to have a better regulatory control of CITES. On the legal perspective, the actions that can be undertaken also involved reviewing the content of CITES for several countries that has a larger number for wildlife trade and to increase the strength of the national legislation. This actions needs to be done immediately due to the fact that most source states, still has a insufficient content to protect these wildlife, due to their category 3 status to the ratification of CITES; meaning that the legislation are not meeting the requirements for the implementation of CITES.

However, the most prominent eradication measure that could be exercised is to gradually change the mindset of the key stakeholders involved within the activities itself. In order to change the pattern, a change in mindset is also necessary. There needs to be advocacy to relevant stakeholders with the agenda of debunking myths of consuming of animal parts while at the same time, regards to the impacts of this activity in the long run, since without this measure extinctions are inevitable.

References

Cites.org. (2018). National laws for implementing the Convention | CITES. [online] Available at: https://cites.org/legislation [Accessed 27 Aug. 2018].

Broad, S., T. Mulliken, and D. Roe. 2003. The nature and extent of legal and illegal trade in wildlife. In Oldfield, S. (ed.) The Trade in Wildlife: Regulation for Conservation. UK and USA: Earthscan.

Nooren, H. and G. Claridge. 2001. Wildlife trade in Laos: the end of the game. The Netherlands Committee for IUCN, Amsterdam.

Nash. S. ed. 1997. Fin, feather, scale and skin: observations on the wildlife trade in Lao PDR and Vietnam. Petaling Jaya, Malaysia: TRAFFIC Southeast Asia.

TRAFFIC Southeast Asia. 2004. Armored but endangered. Asian Geographic (4)

SFNC. 2003b. Implementation of actions against the extraction and trade in wildlife at the Pu Mat National Park: proceedings of a workshop held on 27 June 2003 in Vinh City, Nghe An province. S. Roberton, F. Momberg & Tran Chi Trung. SFNC project, Vinh.

SFNC. 2003a. Hunting and trading wildlife – an investigation into the extraction and trade in wildlife around the Pu Mat National Park. S. Roberton, Tran Chi Trung & F. Momberg, SSFNC project, Vinh.

—

This article was written by Aicha Grade Rebecca, an undergraduate student at the Faculty of Law Universitas Gadjah Mada, doing an internship at the Center for Southeast Asian Social Studies (CESASS).

The Errors in Various Legal Frameworks Regulating Piracy Activities in Southeast Asia

Introduction

What comes into your mind when you heard the word “pirates?” is it Captain Hook from the Disney movie “Peter Pan” with an eye patch? Is it a hungry and angry guy from Somalia trying to hijack the Maersk Alabama in “Captain Phillips?” However, other than focusing on how the popular media trying to portray how pirates actually looked like, we shall be aware that actual piracy activity is something that is closer to home. In fact, Southeast Asia hosted the most piracy activities due to their fragile geographical location and other relevant socio economic factors. The number elevated in between 1995 – 2013 into being the place for 41% total piracy activities. These numbers are quite high when being compared to Somalia (18%) and West African Coast (13%) .

Based on Adam Mccauley from TIMES, more than 120.000 ships passes through the Indonesia- Malaysia- Singapore which makes it a vital waterways and trade routes for international economic and trading activities. The data conducted in the year of 2010 proven that piracy drains $7 Billion – $12 Billion US Dollars each year from the global economy creates an urgencies for parties to both eradications and analysis of these occurrences.

Therefore, other than describing the maritime security policies of the respective Southeast Asian states, this article means is to assess both legal and socio – economic factor that resulted into international criminal activity to keep occurring in Southeast Asian waters. Starting from the problems of defining “Piracy” in UNCLOS and other conventions, Geographical locations, legal complications due to overlapping jurisdiction and to assess the corruption activities of states that contribute to the existences of these activities.

UNCLOS; Unsuitable to Govern Piracy in Southeast Asia?

The measure to prevent and eradicate piracy activities has already been regulated on the UNCLOS (United Nations Conventions on Law of The Sea). This documents is the most prominent legal documents that regulates most aspect on ocean governance systems, despite their Mare Liberum & Res Communis status. This conventions governs baselines, states rights over their respective sea area as well as natural resources contains within it and how human beings cultivate these resources. The definition of “piracy” itself that is contained within UNCLOS is “any illegal acts committed for private ends by the crew or passengers and directed on the high seas and outside the jurisdictions of any state” . However, this is problematic in a way that piracy within the territorial seas are not included within the context of piracy contained in the aforementioned articles.

This practices resulted into piracy activities happening in the territorial sea area, even though the ship of their own nationals are the victim of the attacks. Mostly, these hijacking activities are conducted with smaller vessels and would only resulted into these activities to be considered as theft / armed robbery . Research also proven that both African/Southeast Asian region have different characteristic when it comes to piracy, since in the latter region, piracy are predominantly hijacking tankers to steal oil cargos other than kidnapping and asking for ransom in return.

The legal definition of the concept of piracy as written in the aforementioned documents created a legal implications where the writer believes that it created a reality where most of these “minor” piracy perpetrators goes free due to the point that this documents failed to address the problem of piracy activities in the territorial waters and the traits of piracy that is happening in Southeast Asia. These problems are the reason why the Straits of Melacca are considered to be a war risks premium area by the Joint War Committee (JWC) of the London Market. This facts is the reason why many states in Southeast Asia come up with both bilateral & joint cooperation agreement in order to tackle piracy activities, such as the Regional Co-Operation Agreement in Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ship In Asia (ReCAAP) where states shares information conducts cooperative arrangements in order to eradicate piracy, and other bilateral joint agreement.

Cooperation Is Not Enough – ReCAAP is not enough.

However, by regulating the ReCAAP does not mean that the problem of Piracy is immediately solved. This is due to various political interests and other socio – economic factors that has been going on within the region. On the political sectors, most of ReCAAP members are ASEAN members. This leads to a non – interventionist approach into various matters where states are hesitant to interfere in other state’s affairs due to the fact that for years, ASEAN believes in harmonious co – existence where states exists alongside others with respect to sovereignty. Furthermore, some states are still reluctant to share information that could not be beneficial for their national interest.

The implications of the aforesaid statements are quite detrimental in the long run in a sense where political interests are one of the biggest obstacles in the process of eradicating Piracy in Southeast Asia. The geographical contour of Southeast Asia that is mainly made out of intersecting economic exclusive zones and straits goes along a several regions made eradication process impossible due to the fact that states has their own sovereignty rights in order to protect their areas in which includes their waters. Although International Law and Law of the Sea recognizes the practice of Hot Pursuit or the rights of coastal state to conduct a pursuit of a foreign vessel all the way to the high seas, these practices are in fact, limited in reality. Furthermore, the compositions of Indonesia that is made up of thousands of islands could makes it harder for ocean patrol to eradicate piracy due to the fact when this event occurred, the perpetrators could easily hide in one of the islands that is located near to the area.

Solutions and Possible Legal Frameworks

Thus, after doing a brief research of the subject matter, the writer come up with three approach in order to tackle the aforementioned problems by approaching it through 3 different aspects; such as Legal, Political & Socio Economical Part. The writer believed that in order to tackle a problem that has been going on for quite some time and deeply rooted within the region, this approach must be done in order to prevent, maintain and eradicate, all at once.

In the legal aspects, there must be an understanding that there are actual differences between the concept of “piracy” and “contemporary piracy”. The concept of piracy are concept that is derived from the western world and it involved element of war where the master and the crew of the vessel is usually taken as hostage. However, contemporary piracy are usually conducted in smaller boats and the activity that is usually conducted are theft that could resulted into private entity experiencing losses, even before the goods reached the port of destination. Thus, there needs to be an expansion of the legal definition of piracy due to the fact that in the region, people are usually conducting piracy for purely, economic motives.

In the political aspects, there must be an increase of cooperation between states (especially coastal ones) to conduct more joint cooperation in order to eradicate piracy. This could means more information sharing platform between regions in order to become more transparent in regards to any information concerning these activities. In the past few years, the effort has not been very effective due to the fact that states still highly concerns that transparency would resulted into their states to be deemed as weak and vulnerable against these attacks, while in fact transparency are the most integral part into the battle against piracy. In the aspect of technicalities, there must be also standardized and uniformed standards and protocols when it comes to ways to conserve the vessel and the goods contained within it whenever this kind of event occurred, and this must be apply by all vessels that sails through the ASEAN waters.

And lastly, the 2 efforts above could not be implemented if it is not being paired with a good approach towards the socio – economic factors of the region as well. There needs to be a socialization process by the regions that consists of government, state actors as well as non governmental actors to help the people, especially the one with the lower status living in the coastal area, about the danger of this activity and how it can be detrimental towards the status of maritime security of a country. Also, there needs to be cooperatives between parties to create initiatives in regards of finding alternative source of income for people living in the area who is prone to this kind of activities. With that, we could hope that the society could be more proactive and would be willing to cooperate with the government, to help eradicate this kind of crime once and for all.

Law & Legislations References

United Nations Conventions on Law of The Sea

Code of Practice for the Investigation of Crimes of Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) Assembly Resolution A.1025

Regional Co-Operation Agreement in Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ship In Asia (ReCAAP)

Journals References

Apjjf. Org. (2018). Security in the Straits of Malacca. The Asia – Pacific Journal: Japan Focus [Online] Available At: Https//apjjf.org/Nazery – Khalid/2042. Article. Html.

Forster, B (2014). Modern Maritime Piracy: An Overview of Somali Piracy, Gulf of Guinea Piracy and South East Asian Piracy. British Journal of Economics, Management & Trade 4 (8). Pp. 1251 – 1272